A History of Early American Popular Music

1892-1915

A good old-fashioned girl

with heart so true

One

who loves nobody else but you[1]

Dominic

Vautier 4-11

Early American popular music is

a fairly unknown part of our

history. It is also an interesting part because,

as may be the case with any attempt to recall times and things past, unrelated factors

can influence and even obscure what we perceive took place.

I will try to explain not just the music but also some social aspects of this time, 1892

to 1915 that undoubtedly influenced the music. The dates are important because they signal a specific change

in

perception, direction and attitude of America toward

its everyday music. Popular music emerged not just as an industry but also as an economic

force. At this transitional time popular music began to address real

social issues, not just moons and Junes as we are liked to believe.

The

emerging middle class came to see popular music more as an expression

of their own values, talents and enjoyments, and as being really “middle class”,

as opposed to something restrictively Victorian, "high brow", and much less exuberant.

In short, the emerging middle class saw popular music as a mirror of

itself.

Early American popular music is

a fairly unknown part of our

history. It is also an interesting part because,

as may be the case with any attempt to recall times and things past, unrelated factors

can influence and even obscure what we perceive took place.

I will try to explain not just the music but also some social aspects of this time, 1892

to 1915 that undoubtedly influenced the music. The dates are important because they signal a specific change

in

perception, direction and attitude of America toward

its everyday music. Popular music emerged not just as an industry but also as an economic

force. At this transitional time popular music began to address real

social issues, not just moons and Junes as we are liked to believe.

The

emerging middle class came to see popular music more as an expression

of their own values, talents and enjoyments, and as being really “middle class”,

as opposed to something restrictively Victorian, "high brow", and much less exuberant.

In short, the emerging middle class saw popular music as a mirror of

itself.

What is presented here as “popular” is that

collection of melodies in

sheet music form and later in recorded form that was successful in the

general market place, and that people were

willing to spend valuable money on to have, play and

enjoy. This is actual music Americans sang and danced to. Our

present-day opinions about how important it was a hundred

years ago may lead people to pass judgment on which songs

were artistically significant. This argument is perhaps weak compared to the best measuring tool of all, the raw

dollars that popular music cost people to buy. So music that sold

millions of copies tell

us best which songs made a difference to Americans.

In this context the term “popular”

needs to be a little better defined.

Here I am tempted to consider music that was widely sold, that is, was

widely popular. But the

designation “popular music” was a term that developed around the

turn of the 1900's to refer to more--a specific type

of music. This type of music was

specifically designed to appeal to large and diverse segments of the

American public by employing musical elements that everyone wanted and liked.

The music targeted a rising middle class in particular by using

a form and content that was most associated with their expectations and

accelerating lifestyles. The

framework originally developed by Stephen Foster and perfected by

Harry Von Tilzer,

Ernest Ball, Joe

Howard, and others was highly effective in this respect,

and contributed in no small way to the sudden rapid growth and overwhelming

success of this type of music.

That movement was so effective that it consequently became

permanent, and that fad became what we know today as “popular music”.

So I talk

about

several topics that seemed to have influenced early popular music.

First of all I think that the music was strongly interdisciplinary, because

it

deals with a society that largely affected musical history

of this period, and was in turn itself affected. Bloomers, which appear to have nothing to do with this topic, are

instead a microcosm of a larger movement, being both an element of fashion and a

symbol of some of the changes at this time, namely the entry of

women into the work force, the drive toward increased independence for

women and a greater acceptance of female equality.

Wearing bloomers for example implied that it was not just men who

“wore the pants.” The mere mention of bloomers can be associated with

the same insouciance that pervaded early American popular music. Women who wore

bloomers

were pushing the envelope of what was permissible, but in greater and

greater numbers. Even “nice” girls began to wear bloomers,

although bloomers were considered years earlier as only proper undergarments.

Any woman who wore them, mentioned them, liked them, was

symbolically displaying an affinity for what had heretofore been off

limits and relegated to the bedroom. Including sex.

Did you ever see a maiden

when she’s riding on her wheel?

Did you ever see a maiden

when she’s riding on her wheel?

How she wears her baggy bloomers that her limbs she may conceal?[2]

Sex also is a big consideration,

because there has been an inseparable relationship that music has

with physical aspects of the human condition, and this is a good

reason why songs of this period cannot help but be sexual. Beginning in 1900 the walls of Victorian conservatism,

strongly influencing American music for over 60 years before this time, began to give way, and by 1909 popular

music was radically different from the music of just ten years before,

openly promoting obvious sexual indiscretions, although in a style carefully cloaked in

double-meaning and metaphor.

I ain’t had no loven’ since

January, February, June, or July.[3]

A hug he’d give her then

He’d kiss her now and then,

They would kiss again, then

He would row, row, row[4]

Like to feel your cheek so rosy

Like to make you comfy, cozy

‘cause I love from head to toesy[5]

If I could be with you I’d love you

strong.

If I could be with you I’d love you

long.[6]

The period explored here is not well known.

It

could be the absence of war and the consequent perception that this time

in our history was uneventful, placid and peaceful--that is to say, boring.

The frontier was gone and high adventure was at a premium. Billy the Kid was dead along with Jesse James, as well as the

larger-than-life lawmen who pursued these symbols of the Wild West.

The heroic accomplishments that tend to fill pages of

chronologies came from a bygone age, not this one.

And in addition only one small war occurred. These may be some of the reasons why this period was

a parenthesis in time, but there is

no reason to ignore it for great musical value was there. The music was rich and most of all formative.

As matters

now stand, a key page from the gospel of music is lost to us.

This era also suffers from the human

tendency to interpret the past in ways that conform to our current

tastes and that reinforce our favorite stereotypes. For example, Meet Me in St.

Louis Louis was not much of an earth-shattering song when it was

first published, selling perhaps a respectable 200,000 copies of sheet

music. It enjoyed a very

successful rebirth in  1941

in a movie of the same name starring Judy Garland. Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis

has, in some minds, incorrectly come to represent the very embodiment of

turn-of-the-century popular music, but in truth its part was minor.

1941

in a movie of the same name starring Judy Garland. Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis

has, in some minds, incorrectly come to represent the very embodiment of

turn-of-the-century popular music, but in truth its part was minor.

Maple

Leaf Rag was also a success and also heavily associated with the

time, but Classic Ragtime never lasted very

long nor was it very successful. Current

thinking distorts the picture with a misconception that Classic

Ragtime absolutely dominated the marketplace, which it did not. Once again a song that was comparatively peripheral has been

retrofitted, so it can serve as a convenient

and more commercially viable symbol.

Most of the illustrations contained here have

been done in the style of the era. It is my hope that these graphics provide some contemporary flavor.

Popular music tradition had its beginnings with

Stephen Foster. He based his music loosely on the traditional English ballad,

local work songs, and black spiritual music. He developed the standard verse and the 16-measure chorus.

He installed many devices that helped people remember the

words and music. His tunes

were simple, repetitious, and heavily melodic. That’s the way

he thought Americans liked their music, that’s the music they danced

to and worked to, and that’s the music they most easily remembered.

Origins of popular music

Ed

Christy’s Minstrels and other groups carried Foster’s

tradition forward in the years following the Civil War. Songwriters such as Harry Kennedy, Ted Harrigan, and James Bland

were, by 1880, turning out fairly good music very much in the Foster tradition.

In fact, James Bland's style is strikingly Fosterish, as seen in such

ballads as In

The Evening By the Moonlight and Oh

Dem Golden Slippers. These early songwriters gradually began to migrate to New York City prior to 1880 because popular music

writing had been largely

taken over by the songwriters and publishers located in

Manhattan.

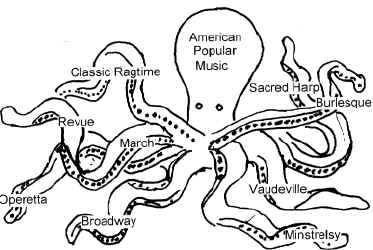

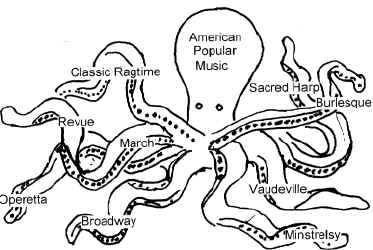

By the 1890’s

popular music intensified its habit of voraciously borrowing anything that was good and publishable, Vaudeville, Broadway, and

minstrelsy being its major sources. This trend went on until minstrelsy faded and Vaudeville moved to

Hollywood. But popular music continued to

draw its material from Broadway, and turned to emerging

music sources such as Jazz, Swing, Big Band, The Blues, and later,

Rock ‘n Roll and Country. See Origins

of Popular Music in America

for more on this subject.

Original

Baby Boomers

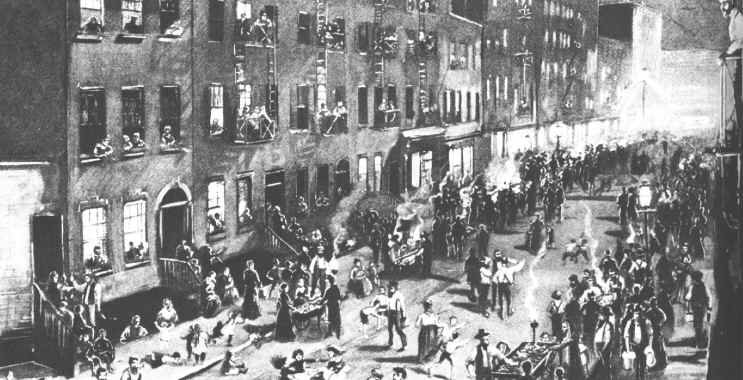

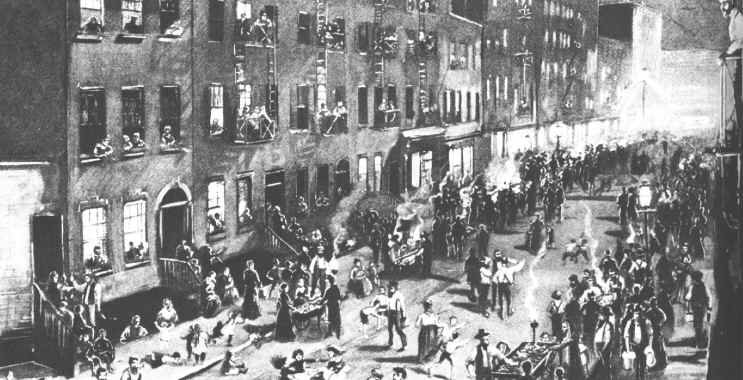

Other reasons

existed for the phenomenal success of popular music starting in the

1890’s, not the least of which was the growth of urban populations.

These populations more

than doubled during the period from just after the Civil War to 1900.

This growth was fueled by rural residents who were

attracted to big-city jobs, entertainment, and lifestyles. Immigration played an important part in the buildup of

population. Although the

actual proportion of immigrants was only 7 percent then, many of these immigrants

gravitated to the music and entertainment business so their participation

in musical

development was much more significant, adding to it a richness and

international character that it may never have possessed otherwise.

American popular music is universal because it was born of immigrants. See more

in my section The First

Baby Boom.

Other reasons

existed for the phenomenal success of popular music starting in the

1890’s, not the least of which was the growth of urban populations.

These populations more

than doubled during the period from just after the Civil War to 1900.

This growth was fueled by rural residents who were

attracted to big-city jobs, entertainment, and lifestyles. Immigration played an important part in the buildup of

population. Although the

actual proportion of immigrants was only 7 percent then, many of these immigrants

gravitated to the music and entertainment business so their participation

in musical

development was much more significant, adding to it a richness and

international character that it may never have possessed otherwise.

American popular music is universal because it was born of immigrants. See more

in my section The First

Baby Boom.

Pianos

The huge popularity

of this music didn’t come about by accident. For years piano manufacturers had been steadily increasing their

output of pianos and harmoniums,[7]

and at the same time conducting an effective campaign of

so-called “culturization” to educate people. Sales were up, and the number of new piano students was ever

growing. This effort was

well rewarded, because rapid growth in the sale of pianos had long

been awaited and expected by these manufacturers. See the section The

Piano.

Dancing

Along

with the growth of cities came a corresponding increase in entertainment, in particular dance halls, ballrooms, and amusement

parks. This new type of music

largely catered to dance, dominated by the slow American waltz and

fast ragtime one-steps which were becoming a sensation among young

people. All successful sheet

music of this time was, by its very nature and without exception, dance

music, most often in slow American waltz time. See my section on Dancing.

Along

with the growth of cities came a corresponding increase in entertainment, in particular dance halls, ballrooms, and amusement

parks. This new type of music

largely catered to dance, dominated by the slow American waltz and

fast ragtime one-steps which were becoming a sensation among young

people. All successful sheet

music of this time was, by its very nature and without exception, dance

music, most often in slow American waltz time. See my section on Dancing.

Sheet

Music

Sheet-music

sales were spectacular as well. Before

1892 a 50,000-copy sale was a big deal, but such a sale after 1892 was disappointing.

Million-copy sales were the norm after 1892, and there were

probably 100 such million-copy hits between that time and 1915 [8]

The beginning of early popular-music was marked by big

sales of sheet music and began to end by 1915.

See Sheet Music for more on

this subject.

Recorded

Music

The birth

of the phonograph sounded the death-knoll for sheet music. Record

players

altogether changed the nature of popular music because the media had a

lot more to do with the message. It

wasn’t so much the music anymore, but rather, how and where it could

be presented. By 1915,

recording stars began to appear and music

became portable. It became a

spectator sport. See Recorded

Music.

Sex

in Early Music

Almost unknown

before 1892, a type of “social

song” came into prominence, one that made relative and meaningful

social comment. Social songs[9]

addressed such issues as prostitution and sexual relationships, topics

that were absolutely not allowed in popular music before this time.

Victorian restraint was still strong, and popular music had to

confront a well-entrenched set of moral taboos.

Songwriters

developed ways to get around sexual restrictions, mainly by the use of

ambiguous words and phrases, disguises, metaphor, symbolism, and code

words.[10]

From about 1900 to 1909, music radically changed in the way it

handled topics of a sexual nature. Efforts

to challenge the long-standing Victorian caveats by the more famous

songwriters, such as Harry Von Tilzer, Cole and Johnson,

Irving Berlin,

and Al Piantadosi, began to yield results, and the public started to

accept and buy these their songs. To

the shock and disbelief of the old order, premarital sex, petting,

clandestine rendezvous, and kissing became favorite song topics.

This is discussed in more detail at Sex in Music.

Songwriters

developed ways to get around sexual restrictions, mainly by the use of

ambiguous words and phrases, disguises, metaphor, symbolism, and code

words.[10]

From about 1900 to 1909, music radically changed in the way it

handled topics of a sexual nature. Efforts

to challenge the long-standing Victorian caveats by the more famous

songwriters, such as Harry Von Tilzer, Cole and Johnson,

Irving Berlin,

and Al Piantadosi, began to yield results, and the public started to

accept and buy these their songs. To

the shock and disbelief of the old order, premarital sex, petting,

clandestine rendezvous, and kissing became favorite song topics.

This is discussed in more detail at Sex in Music.

Music helped Women's Rights

Women also played a

significant part in the evolution of modern popular song. The music reflected

changes in dress, recreational habits, and moral conduct, and it

encouraged independence and self-awareness among women. Music may have brought the bicycle into common use or at least contributed to the bicycle

fad. In any case the bicycle fad of

the 1890’s radically changed dress styles and altered society’s

perception of women. See Women's Rights.

The songwriters of early popular music

who came together in New York

beginning around 1888 were a diverse collection of talent. Their

backgrounds were as different as night and day. Many came from

poverty, and many more were drawn to the city from other places

especially the Midwest

and South in search of opportunity. Others came from foreign

shores: Jews fleeing the oppression they had been subjected to in

Russia, Germans forsaking a fatherland ravaged by war, Irish escaping

intense poverty and hunger, Italians wanting a better life, Greeks and Armenians

seeking a stable and democratic government, and blacks looking

for a life free of hatred and discrimination. All shared a common

purpose: all were driven by a desire to write or play music. They

wanted to be involved in the music industry, not producing just any

music. it had to be of the people, music that best represented the

backgrounds they themselves had come from and still maintained

sentimental attachments to. However diverse their backgrounds, they

participated in nearly identical everyday life experiences in the big

city. They lived in close proximity to the same saloons, flop houses,

brothels, vaudeville theaters, Broadway shows, and beer gardens. They

were all exposed to the divergent variety of life in the tenderloin, the

Lower East Side, and especially the Bowery. To look further into this see

The

Songwriters of Tin Pan Alley.

Probably

no fewer than 10,000 moderately successful songs were produced by Tin

Pan Alley between 1892 and 1915. A

few of the songs from that time are still heard on occasion such as Take

Me Out to the Ball Game, Sweet

Adeline, Bill Bailey, Sidewalks

of New York, Daisy Bell, and Bird in a Gilded Cage. But the vast majority of these early

songs have been pretty much forgotten.

A

Few Stories

One

of the more interesting aspects of this early music were the flashes of

insight, inspirations, situations, and urban legends surrounding these

compositions. Some of

the stories perhaps were anecdotal or invented simply to gain publicity.

But in general, we have to believe that the interesting little tidbits

of folklore surrounding these early songs very well may have happened.

We like to believe they happened anyway. So

here are a few stories about how some songs were made.

Popular music

came into a world that was set for change. The

evolution during that period was far greater than what we are accustomed to today.

In our present society, order and custom have been well

established for years, and the extent of discomfort we experience due

to change usually translates into little more than relative

inconvenience. On the

other hand, the changes that affected Americans in the two decades

surrounding the turn of the 20th century were deep-seated. They dealt

with issues close to the heart; that is, they involved profound

re-adjustments in values and perceptions. These changes were often necessitated by the dislocation of

people from farms and foreign soil to American cities, places of

uncomfortable customs and different lifestyles.

One

thing that these transplanted arrivals to New York could share was the music.

They might not necessarily share the music of

Germany

or

Greece

or

Tennessee

or

South Carolina, but they all responded to the American music of the day.

The street music was sung by merchants, vendors,

hurdy-gurdies, trolley car riders, and passers-by. It spoke of baseball, girlies, canoe rides, the subway, and

trips to Coney Island, the things that helped these newly arrived

people feel at home in their unfamiliar surroundings. Music was their language, their first introduction to this way of life, for indeed the music spoke its own kind of

language, a universal language.

During summers on the East Side, people left their insufferably hot tenements

and took refuge in the streets to talk, barbecue, gossip, play, drink,

dance, and sing. What did

they sing? In the Italian

neighborhoods, they sang Italian songs, and in the Irish

neighborhoods, they sang Irish songs. But what did they sing when they all got together?

They sang After the Ball,

Daisy Bell, The Band Played

On, and

Moonlight Bay. They sang American

popular songs.

A Chronology and Other Things

I have developed a year-by-year

history of these times. Each year from 1892 until 1899 is

discussed in chronology one

and from 1900 through 1915 in chronology two.

I have also put together a list of million-sellers

during this period as well as some of my favorite recorded

music.

Here are some other links in this

article:

Origins

of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People

Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

How

Dancing Helped Music

Women

and Early Music

Some

Early Songwriters

Some

Songs

The

Influence of the Piano

Recorded

Music

Sheet Music

Chronicles

1892-1900

Chronicles

1901-1915

Million

Sellers

[1]

Will Dillon and Harry Von Tilzer, I

Want a Girl, Just Like the Girl That Married Dear Old Dad, 1909.

[2]

Douglas Gilbert, Lost Chords:

The Diverting Story of American Popular Songs (New York: Cooper

Square Publishers, Inc., 1942), 215.

[3]

Jack Norworth & Nora Bayes, Shine

On Harvest Moon, 1908.

[4]

William Jerome and Jimmy Monaco, Row,

Row, Row, 1912.

[5]

Otto Hauerbach and Karl Hoschna, Cuddle

Up a Little Closer, 1908.

[6]

Henry Creamer, If I could Be

With You One Hour Tonight, 1926.

[7]

A small foot-pumped reed organ.

Also called the parlor organ.

[8]

Appendix I contains a list of million-sellers.

[9]

Appendix VI is an analysis of social songs from 1880 to 1915.

[10] Code words are words that have special meaning within

a subculture.

Early American popular music is

a fairly unknown part of our

history. It is also an interesting part because,

as may be the case with any attempt to recall times and things past, unrelated factors

can influence and even obscure what we perceive took place.

I will try to explain not just the music but also some social aspects of this time, 1892

to 1915 that undoubtedly influenced the music. The dates are important because they signal a specific change

in

perception, direction and attitude of America toward

its everyday music. Popular music emerged not just as an industry but also as an economic

force. At this transitional time popular music began to address real

social issues, not just moons and Junes as we are liked to believe.

The

emerging middle class came to see popular music more as an expression

of their own values, talents and enjoyments, and as being really “middle class”,

as opposed to something restrictively Victorian, "high brow", and much less exuberant.

In short, the emerging middle class saw popular music as a mirror of

itself.

Early American popular music is

a fairly unknown part of our

history. It is also an interesting part because,

as may be the case with any attempt to recall times and things past, unrelated factors

can influence and even obscure what we perceive took place.

I will try to explain not just the music but also some social aspects of this time, 1892

to 1915 that undoubtedly influenced the music. The dates are important because they signal a specific change

in

perception, direction and attitude of America toward

its everyday music. Popular music emerged not just as an industry but also as an economic

force. At this transitional time popular music began to address real

social issues, not just moons and Junes as we are liked to believe.

The

emerging middle class came to see popular music more as an expression

of their own values, talents and enjoyments, and as being really “middle class”,

as opposed to something restrictively Victorian, "high brow", and much less exuberant.

In short, the emerging middle class saw popular music as a mirror of

itself.

Did you ever see a maiden

when she’s riding on her wheel?

Did you ever see a maiden

when she’s riding on her wheel? 1941

in a movie of the same name starring Judy Garland. Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis

has, in some minds, incorrectly come to represent the very embodiment of

turn-of-the-century popular music, but in truth its part was minor.

1941

in a movie of the same name starring Judy Garland. Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis

has, in some minds, incorrectly come to represent the very embodiment of

turn-of-the-century popular music, but in truth its part was minor.

Along

with the growth of cities came a corresponding increase in entertainment, in particular dance halls, ballrooms, and amusement

parks. This new type of music

largely catered to dance, dominated by the slow American waltz and

fast ragtime one-steps which were becoming a sensation among young

people. All successful sheet

music of this time was, by its very nature and without exception, dance

music, most often in slow American waltz time. See my section on

Along

with the growth of cities came a corresponding increase in entertainment, in particular dance halls, ballrooms, and amusement

parks. This new type of music

largely catered to dance, dominated by the slow American waltz and

fast ragtime one-steps which were becoming a sensation among young

people. All successful sheet

music of this time was, by its very nature and without exception, dance

music, most often in slow American waltz time. See my section on

Songwriters

developed ways to get around sexual restrictions, mainly by the use of

ambiguous words and phrases, disguises, metaphor, symbolism, and code

words.

Songwriters

developed ways to get around sexual restrictions, mainly by the use of

ambiguous words and phrases, disguises, metaphor, symbolism, and code

words.