Sheet

Music

Dominic Vautier 4-11

Keep the love light glowing

in your eyes so true

Let me call you “Sweetheart” I’m in love with you.[1]

For

most of this country’s history, sheet music has been the guardian and

record keeper for song. It was the only media available to the industry

for all of the 18th and 19th centuries and for the

early part of the 20th century. No other way to communicate song existed except by word of mouth.

Before there was any such thing as radio or phonograph records,

sheet music was it. Long

before reel-to-reel tape recorders, CD’s, audio cassettes, video

cassettes, or even movie soundtracks, sheet music was the way a song was

recorded, played, transcribed, and remembered.

For

most of this country’s history, sheet music has been the guardian and

record keeper for song. It was the only media available to the industry

for all of the 18th and 19th centuries and for the

early part of the 20th century. No other way to communicate song existed except by word of mouth.

Before there was any such thing as radio or phonograph records,

sheet music was it. Long

before reel-to-reel tape recorders, CD’s, audio cassettes, video

cassettes, or even movie soundtracks, sheet music was the way a song was

recorded, played, transcribed, and remembered.

America

in 1830 was little more than a frontier. It was definitely a frontier as far as music went.

This country depended almost entirely on the Old World for its

music, and much of it was imported from England, France, and Italy.

Some early attempts to

publish local American music did occur. Some single-sheet ballads from the 1830’s[2]

and also some antebellum[3]

pieces can still be found, such as the ‘Corn Cobs’ published in

1836.[4]

But it appears that for the most part, published local American

music was sparse and rather poor in quality compared to the abundance of

fine music flowing out of Europe.

Despite

or maybe because of this feeble American activity, it was not until 1870

that the Library of Congress actually embarked upon the worthwhile but

belated venture of cataloging locally produced sheet music.

Most

of the time, we know who wrote the music but we don’t know too much

about who was responsible for the artwork on the sheet cover page.

Each publishing house usually employed one or more artists to

design the sheet covers, but they didn’t keep records on whom these

artists were.[5]

Even up until the turn of the 20th century, most of

the artists who designed the sheet-music covers remained unknown.

Making

the Sale

Sheet

music didn’t begin to sell heavily until 1892. It reached a high point

in 1910 when two billion copies were sold. That’s 22 sheets of music sold that year for every man, woman

and child in the country. From

then on the industry went into a steady decline. The number of actual sheets sold during the period of greatest

sheet-music production, from 1892 until 1915, was probably somewhere

around 10 billion, a

phenomenal number, considering how it had to be marketed.

Sheet

music could not be sold like other merchandise. The music publishers found out quickly that the standard methods

of retailing did not work at all. An

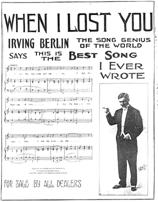

interesting attempt to use traditional advertising techniques occurred

in 1918, when Harry Link, an advertising executive, decided that he

wanted to sell music through normal advertising channels. After complete market saturation of the

Philadelphia

area, he ordered 25,000 advanced copies of a hot, new Berlin song, Smile and Show your Dimple. He

managed to sell only 2,500, and the whole project was a complete

failure.[6]

So

what made the sale of sheet music unique? People simply wanted to hear the music before buying it.

They wanted to sample the goods. It had to be advertised almost by word of mouth or, more

correctly, by word of voice. The

music publishers had to do their own advertising and expose their

products to the listening public at their own expense.[7] In fact, methods of selling music hadn’t changed much from

early 1890 until 1915.

After

1915 it became much easier to advertise music with all the newer methods

of communication, especially radio, which had begun playing music around

1922. A disk jockey could

reach literally millions of people instantly, whereas before mass

communications, it was a much harder job--it was a job for the pluggers.

Pluggers

There

is abundant literature available today that describes the

adventure-packed lives and times of early song pluggers. These industrious entrepreneurs went to great lengths, even

physical confrontation, to succeed in their endeavors against an array

of stalwart competitors. These

people were high-powered, hired salesmen, not unlike the typical used

car or insurance salesmen of today, except that they were oftentimes

also highly motivated, gifted musicians, vaudevillians, and songwriters.

They were paid by the publishers to go out and demonstrate new

songs to anyone they could find who was willing to listen or, more

often, who didn’t want to listen at all. The pluggers were usually paid a wage, but sometimes the money

they earned depended on how hard they worked and how successful they

were at selling the songs that they were hired to advertise.

There

is abundant literature available today that describes the

adventure-packed lives and times of early song pluggers. These industrious entrepreneurs went to great lengths, even

physical confrontation, to succeed in their endeavors against an array

of stalwart competitors. These

people were high-powered, hired salesmen, not unlike the typical used

car or insurance salesmen of today, except that they were oftentimes

also highly motivated, gifted musicians, vaudevillians, and songwriters.

They were paid by the publishers to go out and demonstrate new

songs to anyone they could find who was willing to listen or, more

often, who didn’t want to listen at all. The pluggers were usually paid a wage, but sometimes the money

they earned depended on how hard they worked and how successful they

were at selling the songs that they were hired to advertise.

Often

playing tricks on each other, the pluggers tried to outperform their

rivals: stories abound. Sometimes

pluggers would arrive at a site and find that another plugger had beat

them to the audience. At

other times pluggers would stage fake gatherings to lure their

adversaries away, get their competitors drunk or incapacitated, or give

rivals false leads and false directions, anything to get the competition

out of the way. Yet it was

all in the spirit of the business, and pluggers usually got along well

together. They understood

that music was in the family, that all musicians and song pluggers

shared a common bond, and that it was unwise to alienate a competitor

because someday that competitor could be a partner.

Often

playing tricks on each other, the pluggers tried to outperform their

rivals: stories abound. Sometimes

pluggers would arrive at a site and find that another plugger had beat

them to the audience. At

other times pluggers would stage fake gatherings to lure their

adversaries away, get their competitors drunk or incapacitated, or give

rivals false leads and false directions, anything to get the competition

out of the way. Yet it was

all in the spirit of the business, and pluggers usually got along well

together. They understood

that music was in the family, that all musicians and song pluggers

shared a common bond, and that it was unwise to alienate a competitor

because someday that competitor could be a partner.

No

public place in New York

was safe from the frenzy of the pluggers: beer parlors, music halls,

brothels, theaters, bicycle races, race tracks, boxing matches, parades,

baseball games, election campaigns, amusement parks.[8]

Wherever there were groups of people, there were bound to be song

pluggers.

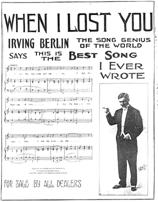

The most successful songwriters, such as

Harry Von Tilzer, Jim

Thornton, and Irving Berlin, started out as song

pluggers. It was a career path, a right of passage, a method of education.

This unique experience gave these songwriters the inside track,

the edge they needed, because it taught them what music would work and

what would not. They gained

an added perspective, like a sixth sense. It was akin to politicians who went out to kiss babies and shake

hands.

Blanch Ring

Sometimes

a publisher, if lucky, could get a big-name vaudevillian to plug

a song, since many of the more popular vaudeville performers were also

pluggers and would work for a fee or a percentage, or even do it as a

favor. If a publisher was

able to get one of the famous female baritones[9]

to plug his song, then he was almost guaranteed a success.

Sometimes

a publisher, if lucky, could get a big-name vaudevillian to plug

a song, since many of the more popular vaudeville performers were also

pluggers and would work for a fee or a percentage, or even do it as a

favor. If a publisher was

able to get one of the famous female baritones[9]

to plug his song, then he was almost guaranteed a success.

The

song plugger has always been needed in one form or another. When radio came along, the disk jockeys took over the roll of

plugger, and the industry continued to work the way it always had, by

demonstration as the primary method of selling. In music stores today there are automatic pluggers, devices where

the buyer is able to select and hear the song before buying it.

Distribution

In

1900 no stores such thing as music stores existed, but music stands were

everywhere; in barber shops, dry goods stores, department stores, and

especially apothecaries (drug stores). The smaller towns didn’t have specialized stores.

Instead, they usually had at least a general store or a barber

shop, which always had sheet music stands.

The

cities had more variety. Larger

stores (J.C. Penney,

Bloomingdale’s, Woolworth, and Macy’s) would sometimes have complete

departments set aside for the sale of sheet music, and the selection

there was much larger. There

was usually a piano on hand and a girl there to play music and

demonstrate songs. These

larger stores preferred to have girls work the music department because

they attracted customers more readily, were less  intimidating,

and played well.

intimidating,

and played well.

If you go to the cinema or rent videos, you know that movies always show

previews (trailers) because it is a good way to advertise new material.

The idea may have come from sheet music. Almost every piece of sheet music contained an advertisement or a

preview of other songs that the publisher had in his inventory. The system worked well because, using these advertising methods

along with the help of pluggers, sheet music sales were very robust for

almost 25 years, from 1892 until 1915.

Sometimes

various manufacturers attempted to print free music sheets so they could

advertise their own products, like corsets, medicines and chamber pots.

It’s hard to determine exactly how successful this practice

was; however, it probably didn’t succeed well based on the number of

surviving examples of this type of advertisement. Besides, selling chamber pots just wouldn’t work too well with

some songs, like I’m Forever

Blowing Bubbles, Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly or After

You’ve Gone.

A

Question of Time

It

took Silver Threads Among the Gold

close to 30 years to sell a million copies. It took Oh Susanna

(1848) even longer. Both

songs can be considered successful. Before the emergence of radios and records, songs took a long

time to get circulated as the distribution system grunted and groaned

along on its ponderous journey. Hot

songs often took a few years to sell a million copies. Some songs were even exported to

England only to come back later as big hits.

It

took Silver Threads Among the Gold

close to 30 years to sell a million copies. It took Oh Susanna

(1848) even longer. Both

songs can be considered successful. Before the emergence of radios and records, songs took a long

time to get circulated as the distribution system grunted and groaned

along on its ponderous journey. Hot

songs often took a few years to sell a million copies. Some songs were even exported to

England only to come back later as big hits.

We

have a hard time seeing this today, since we are used to songs climbing

to the top of the charts within weeks and often disappearing just as

fast. Not so in this early

music period. After

the Ball and Daisy Bell

were able to arrive at million-seller status within one year, which may

translate roughly into less than one week by our time. Likewise Meet Me Tonight in

Dreamland and Let Me Call You

Sweetheart together sold over 10 million copies within one year, an accomplishment against which there is no

comparison in today’s world. Not

even the frenzy of Beatlemania can compare to this shattering pace.

The

Song Sheet Makeup

Sheet

music came in two sizes; the old style song sheet measured about 11

inches wide and 14 inches high, and the smaller size sheet was 9 by 12

inches. Pieces were printed

in the larger size until about 1910, when the piano music holders began

to get smaller and publishers wanted to save paper and transportation

costs. The 9 by 12 size

started appearing about that time and became the standard after the

First World War, but a few of the larger sized sheets continued to be

made as late as 1918. Some

people say the sheet size got smaller to save paper for the war effort,

but that’s hardly a reason at all since we never had a shortage of

paper. Besides, the smaller

size started being sold well before the war.

Some

music came in books of songs, marches, or waltzes, but most of the time

each piece contained one song and was usually made up of one double

folded sheet with a single sheet inside, making a total of three pages

or six sides. Since one side

was for the cover and another for advertisement, four sides were left

for the music. The

songwriters had to consider this problem when they published. Most songs had to be written and arranged in a way that

accommodated four printed pages.

Some

music came in books of songs, marches, or waltzes, but most of the time

each piece contained one song and was usually made up of one double

folded sheet with a single sheet inside, making a total of three pages

or six sides. Since one side

was for the cover and another for advertisement, four sides were left

for the music. The

songwriters had to consider this problem when they published. Most songs had to be written and arranged in a way that

accommodated four printed pages.

The

advertisement was usually a full page on the inside front cover or on

the back, and it generally showed other songs available through the

publisher. Included at the

end of this chapter is a complete song sheet to demonstrate covers,

advertisements, and music. Anthologies

and collections rarely show the complete song sheet.

After

1900 the front cover was often done in color, and some covers are very

artistic. However, more

often there was just a title and the picture of a singer or famous

plugger who popularized the song. This

practice was carried forward into the recording industry, when singing

stars became the main advertisers for a song and often appeared on the

record jacket. The back of

record jackets advertised other songs by the same publisher, a

continuation of the sales practices used in sheet music.

Included

also in the cover was the

Included

also in the cover was the

publishing

house. Publishing houses

had their own logo. Sometimes

there was a picture of the songwriter or lyricist or, more frequently,

the publisher. The copyright

date appears on the inside cover on the first page. Often it was in roman numerals to confuse everybody.

publishing

house. Publishing houses

had their own logo. Sometimes

there was a picture of the songwriter or lyricist or, more frequently,

the publisher. The copyright

date appears on the inside cover on the first page. Often it was in roman numerals to confuse everybody.

Song

sheets did not always have a list price. The

price for a piece of sheet music was could be 25 to 50 cents, although

they could be gotten for less. When

price wars came, the cost could get down to 5 cents a sheet. Publishers could print sheet music for probably 2 cents a copy, so

even at this low bargain price, there was still an opportunity for

profit.

I

have a number of older copies of sheet music shown in their entirety at My

Sheet Music.

Categories

Sheet

music collectors love to organize their material, and here is a typical

breakdown.

Rag

– A rag is anything that has the word “rag”, “ragging”, or

“ragtime” in its title. The

song may or may not be a rag, and even the definition itself can be

confusing. Sheet music

collectors don’t make distinctions between classic or popular rags.

To them it’s all ragtime. Typical

songs under this category are: Nervous

Rag, RagBag Rag, Maple Leaf Rag, Ragging the Baby to Sleep, and Alexander’s

Ragtime Band (which some collectors consider a march or a

rag/march).

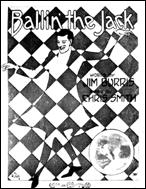

Fox trot - Chris Smith’s Ballin’

the Jack[10]

is considered the first recorded fox trot, but other

foxtrotable (slow slow quick quick) songs were around before Harry Fox, the

inventor of the fox trot. Nevertheless

any song published before 1914 is not considered a real fox trot. Fox trots usually have something on the cover that gives them

away. Typical fox trots

include: Carolina

Fox Trot, Doctor Brown, The Kangaroo Hop, and Palm Beach.

Fox trot - Chris Smith’s Ballin’

the Jack[10]

is considered the first recorded fox trot, but other

foxtrotable (slow slow quick quick) songs were around before Harry Fox, the

inventor of the fox trot. Nevertheless

any song published before 1914 is not considered a real fox trot. Fox trots usually have something on the cover that gives them

away. Typical fox trots

include: Carolina

Fox Trot, Doctor Brown, The Kangaroo Hop, and Palm Beach.

Tearjerker – From 1885 up until 1902, there was a particular type

of emotionally charged song that was labeled a tearjerker. These songs shared the familiar themes of lost love, errant love,

misplaced love, missing love, dead children, dead lovers, injured feelings, and

other kinds of pathos. The

most famous among them was After

the Ball. Tearjerkers

were the forerunners of the torch songs of the 1930’s. The three

kings

of the tearjerker were Harry Kennedy, Paul

Dresser, and Charles

Harris. Most of the songs

were slow waltzes, but they fall into this category mainly because of

their excessively lugubrious content. Some

famous tearjerkers were: Cradle’s

Empty, Baby’s Gone, Fallen, Just Tell Them That You Saw

Me, and

Take Back Your Gold.

Tearjerker – From 1885 up until 1902, there was a particular type

of emotionally charged song that was labeled a tearjerker. These songs shared the familiar themes of lost love, errant love,

misplaced love, missing love, dead children, dead lovers, injured feelings, and

other kinds of pathos. The

most famous among them was After

the Ball. Tearjerkers

were the forerunners of the torch songs of the 1930’s. The three

kings

of the tearjerker were Harry Kennedy, Paul

Dresser, and Charles

Harris. Most of the songs

were slow waltzes, but they fall into this category mainly because of

their excessively lugubrious content. Some

famous tearjerkers were: Cradle’s

Empty, Baby’s Gone, Fallen, Just Tell Them That You Saw

Me, and

Take Back Your Gold.

Waltz – All waltzes, or three-steps, are generally grouped

together, regardless of whether they were Viennese, Bostons, or

Hesitations, which are all variations of the waltz step. This period was almost overwhelmed by waltzes, for

example, Meet Me Tonight in

Dreamland, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her

Now, Let Me Call You Sweetheart,

Bird in a Gilded Cage, and

My

Pal Sal. The last two

songs are also tearjerkers.

Waltz – All waltzes, or three-steps, are generally grouped

together, regardless of whether they were Viennese, Bostons, or

Hesitations, which are all variations of the waltz step. This period was almost overwhelmed by waltzes, for

example, Meet Me Tonight in

Dreamland, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her

Now, Let Me Call You Sweetheart,

Bird in a Gilded Cage, and

My

Pal Sal. The last two

songs are also tearjerkers.

March

– A march is anything that has the

word "march" on the cover and is played in march time. There were a lot of sheet-music marches.

Marches are not strictly popular music. While many of the Sousa pieces became popular, no march ever sold

a million copies, although Washington

Post did come close.

Cakewalk

– Cakewalks are two-steps but they

usually say on the cover that the song is a cakewalk.

Some confusion exists here since we can have cakewalk

two-steps, cakewalk marches, and other variations of this dance. A typical example of confusion is seen with Whistling

Rufus, which is described on the cover as a two-step, polka, and

cakewalk, all at the same time.

Cakewalk

– Cakewalks are two-steps but they

usually say on the cover that the song is a cakewalk.

Some confusion exists here since we can have cakewalk

two-steps, cakewalk marches, and other variations of this dance. A typical example of confusion is seen with Whistling

Rufus, which is described on the cover as a two-step, polka, and

cakewalk, all at the same time.

Blues

- Any song sheet that has “Blues”

on it is Blues. It did not

become popular until after 1915.St. Louis Blues was the first of its kind.

Dialect

– Music done in dialect can be considered dialect or “coon” music.

Racial stereotypes were an acceptable and legitimate vehicle for

musical expression during these early times. Some of the very popular sheet music of the late 19th

century was done in dialect because such songs used fast ragtime

rhythms and syncopation. It

was therefore expected that the dialect songs would have these

qualities. Some very popular

dialect songs, selling over 1 million copies, were I’d

leave my Happy Home for You, If

the Man in the Moon Were a Coon, and

Coon, Coon, Coon.

Indian

Intermezzo – In 1907 a type of song appeared extolling the

adventures and achievements of Native Americans in battle and love.

This group of songs came to be known as Indian Intermezzos,

although they are neither Indian in origin nor are they intermezzos.

Indian Intermezzos are done in cut time[11]

to imitate Indian drums or something like that. Their

sheet covers are often beautifully adorned with bronze or godlike Indian

figures. The most popular of

songs in this group were Red Wing, Silver Heals, and

RedMan.

Two-step

– If a song is labeled “two step” then it belongs in this

category.[12]

Often the sheet cover describes the song in this way. It's

probably a one-step.

Novelty

songs – Items that don’t fit into any of the above categories,

including two-steps, are novelty songs. The content qualifies a song as a novelty.

If the song does not deal with love, lost kids, dancing,

marching, Indians, or dialect, and it's funny then it is probably a novelty song.

A good example is; Who

Threw the Overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s Chowder, On the

5:15, and

He’d Had to Get Under, Get Out and Get Under, and Fix Up His

Automobile.

If you’re not a collector, it is

hard to understand how the tearjerker and Indian intermezzo categories

came into existence in the first place. Most of the other types of sheet music are grouped by music

style, yet these two categories are simply musical content designations,

a distinction that is arbitrary at best. Also, how does one categorize the dialect songs that frequently

became mainstream songs after a short while, such as Bill

Bailey, Goodbye, My Lady Love, and many others?

To sheet music collectors, however,

strict library logic or exact historical context isn’t important.

They just want to organize the types of music the way this music

has always been organized. Tearjerkers

were called that in 1892, and the distinction has stayed with us. To throw all rags together is perfectly legitimate because, to

sheet music collectors, there is no difference between them. A rag is anything that has “rag” in the title.

So Maple Leaf Rag goes with Alexander’s

Ragtime Band just fine, two songs that come from different time periods and

are vastly different. For

the collector it doesn’t matter.

The

End

Well-developed family traditions

had developed in

the decade before the turn of the 20th century which revolved around the parlor piano

and its necessary constituent sheet music. So the Sunday ritual was set: best Sunday clothes, church in the

morning, lunch, afternoon walks in the park, late afternoon visits perhaps, and then an evening around the parlor piano.

In this way the piano and its collection of sheet music became a part of middle-class American life.

But

as

the 20th century moved forward, family institutions began to change.

Children no longer wanted to remain at home after marriage. They even wanted to move to other parts of the country.

Sons who went off to fight the Great War came back with different

attitudes. The war had

profoundly changed them, and in a way, they could never really go home

again.[13]

It was

How 'ya Gonna Keep 'em down on the Farm.

How

you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree.[14]

How

you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree.[14]

Daughters

left to find jobs outside home and, once married, began to do the

unthinkable--postpone having families. Fathers wondered why their offspring no longer wanted to pursue

the family business. The

family unit that supported the purchase and use of sheet music up until

1915 had itself begun to change, and by 1920 the piano, along with

it’s sheet music component, was no longer a part of the essential

family formula.

Piano

sales had been strong all throughout the 1890’s and 1900’s, and lots

of people knew how to play. Not

only that, but popular sheet music was purposely “dumbed-down”, that

is, designed to be easy to play and sing to. There was not very much complexity in chord structure, notation,

or tempo; it was easy stuff for sure. Only one or two years of piano practice provided enough skill to handle just

most of the popular sheet music of

that time.

But

as the next century rolled in, it brought more sophisticated types of

music. It was fine for old

Jake and young Sally to sit down and pick out an American waltz or a

tearjerker in slow time. But

the newer material was of a different sort, and their talent fell short

when confronted with fast rags and syncopated cakewalks. Piano music started becoming more specialized, and this drove out

the many so-so piano players, leaving room for just the good ones.

As piano playing became more difficult, sheet music started to

lose some of its clientele. The

market was being abandoned to the professionals.

Sheet

music also necessitated involvement. There is a fundamental difference between those who sing in a

choir or barbershop quartet and those who merely listen. One role is active and obligatory, while the other is passive and

optional. In one case, creative goals

require effort and sometimes talent. In the other case, attention is purely coincidental and the only

requirement is working ears. The

more intricate sheet music became, the more time it demanded, which was

contrary to the lifestyle that was developing. It just didn’t fit in with the faster pace of life that began

to appear after 1910.

Sheet

music also needed a somewhat large indirect investment. An expensive piano was necessary to be truly part of the sheet

music experience. And the piano

needed a parlor. There had

to be someone who could play, and singers were part of the deal as well.

So this type of music did not come spontaneously, easily, or

quickly. It was not

something that could happen at the turn of switch. It had to be organized.

Sheet

music was not portable. America had

the bicycle, the trolly and by

1915 the car. We were becoming a nation on wheels. People wanted to just pick up and go to the beach, the ocean, the

mountains, the park, and bring their music with them. The record industry was able to satisfy this need.

Portable music was not just a sales gimmick or marketing device. It was a whole new technology replacing an older, obsolete one.

Portable music represented what this younger, on-the-go society

really wanted. Sheet music

was part of the old, tired, effete parlor culture.

Another

reason sheet music died was that it could not handle the new forms of

music, Blues and Jazz. Records

could. The Blues and Jazz

both rely on blue notes, usually a quarter-step flattened third or

fifth, which can’t be done on a piano. Blue notes can be represented in music, sung, and played on many

instruments, including clarinets, trombones, and any other of the

various horns, but it can't be reproduced on a fixed-scale instrument.

It falls between the piano keys, and the sheet music industry was

primarially a supplier of piano music. By 1915 Memphis Blues had become popular.

By 1917 the Original

Dixieland Jazz Band began recording Jazz for Victor, and the sale of

these first Jazz recordings was brisk. But the Jazz sheet music did not do well at all, an ominous sign

of the dwindling interest in sheet music.

Keep

The Love Light Shining

The

era of sheet music began in 1892, when there was a dramatic increase in

the need for popular piano entertainment. Americans suddenly found themselves with leisure time and money

to spend. What did they buy? They bought sheet music by the tons.

The

rapid growth of sheet music sales can also be attributed to the

development of certain traditions that had been building since the Civil

War, such as the need to maintain a strong family unity in an unknown

and sometimes hostile environment. The

wholesale movement to the cities, the rapid increase in the birthrate,

and the huge influx in immigration produced within the family unit a

desire to stabilize and maintain some kind of fixed point by

concentrating on strength and cohesion.

Piano

companies had for years fostered the idea of a family nucleus built

around the piano. The parlor

was a major focus and social center of the home, and every parlor needed a

piano. Accordingly, every

piano needed a good supply of sheet music. Sheet music was one of the things that contributed to stability

because it gave the family something very intimate that they could do

together.

However,

by 1915 the traditional family unit had begun to disintegrate and

children wanted to break away. Young

men and women no longer would live under the same roof with their

parents, nor work the same trades. Society

was beginning to adopt the fast-moving, throwaway mentality that was to

mark the decade of the 1920’s.

The

Blues and Jazz were new music forms that sheet music could not easily

adjust to. Improvisation and

blue notes were beyond the ability of the older forms of piano-based

written music. The natural

spontaneity of Jazz could only be captured in real life or on record.

Of

all the things that destroyed the market for sheet music, none was more

responsible than the record industry, which by 1915 had standardized

methods of recording and reproduction. The record addressed the new American image of mobility,

immediacy, independence, disposability, and even quick wealth.

Like

the McGuffey Reader, sheet music had seen it’s heyday and had left a

deep and abiding imprint on the American psyche. The feeling of family unity was never so strong as when it was

closely associated with that thin, flimsy, easily ripped piece of paper.

Sheet music was thereafter almost to become an American symbol of lost

innocence.

A

Finite Thing

Not

much old sheet music is left today, only a small fraction of the 10

billion originally produced is still in existence.

The sheet music was printed on cheap paper that tended to

turn yellow quickly because of inadequate acid elimination. The inexpensive and flimsy quality of paper also made it tear

easily. Once a sheet got

worn out or ripped, it was discarded (there was no Scotch tape). After all, the stuff was inexpensive, easy to replace and nobody

saw any point in keeping ugly, dog-eard, crumpled-up sheet music around

for very long, especially after it got used a lot. Piano benches tended to fill up rapidly, so with the spring

cleaning, out went a lot of the worn out sheet music. Old sheet music is a finite thing, in

limited quantity, valuable, like gold. Whatever does remain has been gathered and preserved in

collections and displays. There

will never be any more of it produced, ever, and what we now have now is all we will ever have.

Quite

a bit of interest in old sheet music collection exists. Most of the music has been cataloged and priced by collectors.

Pieces generally fall into the 5-dollar range, although rare

copies can sell for much more. The

rarest of all, the apocryphal little-Egypt version of She

Never Saw the Streets of Cairo, is probably quite valuable, if even one

is ever found.

I

sometimes browse my own collection of old

music, wondering how

many times these pieces were played and how many times the pages were

turned. I can imagine the

flow of Daisy

Bell, Teasing, and Can’t You Hear Me Calling, Caroline. The

emotion is there before me on that old paper. I

think the old yellowed paper has absorbed it.

Here are some other links in this

article:

Origins

of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People

Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

How

Dancing Helped Music

Women

and Early Music

Some

Early Songwriters

Some

Songs

The

Influence of the Piano

Recorded

Music

Chronicles

1892-1900

Chronicles

1901-1915

Million

Sellers

[1]

Beth Whitson & Leo Friedman,

Let Me Call You Sweetheart, 1910. This song sold well over 5 million copies and was one of the

most successful sheet music pieces of all time.

[2]

Marian Klamkin, Old Sheet Music: A Pictorial History (New York: Hawthorn Books,

Inc., 1975), 7.

[3]

Before the Civil War.

[4]

Klamkin, 7.

[5]

Klamkin, 10.

[6]

Hazel Meyer, The Gold in Tin Pan Alley (New York: J. B. Lippincott Company,

1958), 48.

[7]

Meyer, 44.

[8]

Meyer, 46.

[9]

They weren’t baritones at all. They were altos who sang in an emotional way.

[10]

Balling the jack means to act quickly and with enthusiasm, as

sailors putting a ball in the gun (jack).

[11]

2/4 time.

[12]

By 1899 the two-step, or march step had disappeared and had been

replaced by the one-step. Music

publishers continued calling it a two-step anyway.

[13]

My father had this experience.

[14]

Rida Young, Lewis & Walter Donaldson, How

Ya Gonna keep ‘Em Down on the Farm After They’ve Seen Paree,

1919.

For

most of this country’s history, sheet music has been the guardian and

record keeper for song. It was the only media available to the industry

for all of the 18th and 19th centuries and for the

early part of the 20th century. No other way to communicate song existed except by word of mouth.

Before there was any such thing as radio or phonograph records,

sheet music was it. Long

before reel-to-reel tape recorders, CD’s, audio cassettes, video

cassettes, or even movie soundtracks, sheet music was the way a song was

recorded, played, transcribed, and remembered.

For

most of this country’s history, sheet music has been the guardian and

record keeper for song. It was the only media available to the industry

for all of the 18th and 19th centuries and for the

early part of the 20th century. No other way to communicate song existed except by word of mouth.

Before there was any such thing as radio or phonograph records,

sheet music was it. Long

before reel-to-reel tape recorders, CD’s, audio cassettes, video

cassettes, or even movie soundtracks, sheet music was the way a song was

recorded, played, transcribed, and remembered.  There

is abundant literature available today that describes the

adventure-packed lives and times of early song pluggers. These industrious entrepreneurs went to great lengths, even

physical confrontation, to succeed in their endeavors against an array

of stalwart competitors. These

people were high-powered, hired salesmen, not unlike the typical used

car or insurance salesmen of today, except that they were oftentimes

also highly motivated, gifted musicians, vaudevillians, and songwriters.

They were paid by the publishers to go out and demonstrate new

songs to anyone they could find who was willing to listen or, more

often, who didn’t want to listen at all. The pluggers were usually paid a wage, but sometimes the money

they earned depended on how hard they worked and how successful they

were at selling the songs that they were hired to advertise.

There

is abundant literature available today that describes the

adventure-packed lives and times of early song pluggers. These industrious entrepreneurs went to great lengths, even

physical confrontation, to succeed in their endeavors against an array

of stalwart competitors. These

people were high-powered, hired salesmen, not unlike the typical used

car or insurance salesmen of today, except that they were oftentimes

also highly motivated, gifted musicians, vaudevillians, and songwriters.

They were paid by the publishers to go out and demonstrate new

songs to anyone they could find who was willing to listen or, more

often, who didn’t want to listen at all. The pluggers were usually paid a wage, but sometimes the money

they earned depended on how hard they worked and how successful they

were at selling the songs that they were hired to advertise. Often

playing tricks on each other, the pluggers tried to outperform their

rivals: stories abound. Sometimes

pluggers would arrive at a site and find that another plugger had beat

them to the audience. At

other times pluggers would stage fake gatherings to lure their

adversaries away, get their competitors drunk or incapacitated, or give

rivals false leads and false directions, anything to get the competition

out of the way. Yet it was

all in the spirit of the business, and pluggers usually got along well

together. They understood

that music was in the family, that all musicians and song pluggers

shared a common bond, and that it was unwise to alienate a competitor

because someday that competitor could be a partner.

Often

playing tricks on each other, the pluggers tried to outperform their

rivals: stories abound. Sometimes

pluggers would arrive at a site and find that another plugger had beat

them to the audience. At

other times pluggers would stage fake gatherings to lure their

adversaries away, get their competitors drunk or incapacitated, or give

rivals false leads and false directions, anything to get the competition

out of the way. Yet it was

all in the spirit of the business, and pluggers usually got along well

together. They understood

that music was in the family, that all musicians and song pluggers

shared a common bond, and that it was unwise to alienate a competitor

because someday that competitor could be a partner.

Sometimes

a publisher, if lucky, could get a big-name vaudevillian to plug

a song, since many of the more popular vaudeville performers were also

pluggers and would work for a fee or a percentage, or even do it as a

favor. If a publisher was

able to get one of the famous female baritones

Sometimes

a publisher, if lucky, could get a big-name vaudevillian to plug

a song, since many of the more popular vaudeville performers were also

pluggers and would work for a fee or a percentage, or even do it as a

favor. If a publisher was

able to get one of the famous female baritones intimidating,

and played well.

intimidating,

and played well.

It

took Silver Threads Among the Gold

close to 30 years to sell a million copies. It took Oh Susanna

(1848) even longer. Both

songs can be considered successful. Before the emergence of radios and records, songs took a long

time to get circulated as the distribution system grunted and groaned

along on its ponderous journey. Hot

songs often took a few years to sell a million copies. Some songs were even exported to

England only to come back later as big hits.

It

took Silver Threads Among the Gold

close to 30 years to sell a million copies. It took Oh Susanna

(1848) even longer. Both

songs can be considered successful. Before the emergence of radios and records, songs took a long

time to get circulated as the distribution system grunted and groaned

along on its ponderous journey. Hot

songs often took a few years to sell a million copies. Some songs were even exported to

England only to come back later as big hits. Some

music came in books of songs, marches, or waltzes, but most of the time

each piece contained one song and was usually made up of one double

folded sheet with a single sheet inside, making a total of three pages

or six sides. Since one side

was for the cover and another for advertisement, four sides were left

for the music. The

songwriters had to consider this problem when they published. Most songs had to be written and arranged in a way that

accommodated four printed pages.

Some

music came in books of songs, marches, or waltzes, but most of the time

each piece contained one song and was usually made up of one double

folded sheet with a single sheet inside, making a total of three pages

or six sides. Since one side

was for the cover and another for advertisement, four sides were left

for the music. The

songwriters had to consider this problem when they published. Most songs had to be written and arranged in a way that

accommodated four printed pages.

Included

also in the cover was the

Included

also in the cover was the Fox trot - Chris Smith’s Ballin’

the Jack

Fox trot - Chris Smith’s Ballin’

the Jack Tearjerker – From 1885 up until 1902, there was a particular type

of emotionally charged song that was labeled a tearjerker. These songs shared the familiar themes of lost love, errant love,

misplaced love, missing love, dead children, dead lovers, injured feelings, and

other kinds of pathos. The

most famous among them was

Tearjerker – From 1885 up until 1902, there was a particular type

of emotionally charged song that was labeled a tearjerker. These songs shared the familiar themes of lost love, errant love,

misplaced love, missing love, dead children, dead lovers, injured feelings, and

other kinds of pathos. The

most famous among them was  Waltz – All waltzes, or three-steps, are generally grouped

together, regardless of whether they were Viennese, Bostons, or

Hesitations, which are all variations of the waltz step. This period was almost overwhelmed by waltzes, for

example,

Waltz – All waltzes, or three-steps, are generally grouped

together, regardless of whether they were Viennese, Bostons, or

Hesitations, which are all variations of the waltz step. This period was almost overwhelmed by waltzes, for

example,  Cakewalk

– Cakewalks are two-steps but they

usually say on the cover that the song is a cakewalk.

Some confusion exists here since we can have cakewalk

two-steps, cakewalk marches, and other variations of this dance. A typical example of confusion is seen with

Cakewalk

– Cakewalks are two-steps but they

usually say on the cover that the song is a cakewalk.

Some confusion exists here since we can have cakewalk

two-steps, cakewalk marches, and other variations of this dance. A typical example of confusion is seen with How

you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree.

How

you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm after they’ve seen Paree.