Dominic Vautier 8/7/2011

The tots play “ring-a-rosie”,

London Bridge is falling down,

Boys and girls together,

me and Mamie O’Rourke,

Trip the light fantastic

on the sidewalks of

New York[1]

How

did the market for sheet music grow so fast and get so enormous?

Why were people suddenly so eager to buy millions and millions of

songs? Who were the

consumers? Where did they all come from?

In 1892, the trickle of music buyers became a flood, and the trend only increased. Two billion copies of sheet music were sold in 1910 alone.

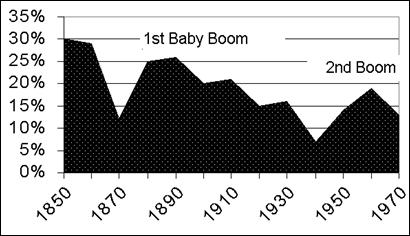

Part of the reason for this sudden change may lie in a significant increase in the youthful part of the population, which I like to call the first baby boom

There was a “baby boom” after the Second World War. During those years, 1946 until about 1958, a lot of babies were born, 60 million in fact. As these kids moved through the demographic spectrum, they brought with them fright, confusion, frustration, revolution, and drugs and social turmoil. At first, these kids just affected the baby industry with shortages of diapers, baby bottles, baby sitters, canning lids, safety pins, baby powder, etc. Things got worse as the babies grew up. Kindergartens and grade schools began to suffer the same fate as the producers of diapers and baby bottles, staggering under the demands of this huge group of consumers. The toy industries on the other hand, didn’t do any staggering at all: they loved it and got rich. On into high school this formidable phalanx of boomers moved, shifting their demands to the sports and entertainment industries. In college, these same young people began to demonstrate against injustice, war, and police brutality. They created hippie communes and New Left organizations. They formed bands that played wild music, and held rallies and huge rock concerts. They started a whole sub-culture.

A baby boom is a sudden bulge in birthrate creating a

larger-than-normal percentage of young people. More than just that, it’s a bulge that is not expected or

that goes against demographic trends. If there were a sudden increase in the percentage of children

from 23 percent in 1945 to 28 percent in 1956 we could probably call

that a baby boom, which we in fact do. This becomes more apparent by looking at census records going

back to 1900 [2].

A baby boom is a sudden bulge in birthrate creating a

larger-than-normal percentage of young people. More than just that, it’s a bulge that is not expected or

that goes against demographic trends. If there were a sudden increase in the percentage of children

from 23 percent in 1945 to 28 percent in 1956 we could probably call

that a baby boom, which we in fact do. This becomes more apparent by looking at census records going

back to 1900 [2].

|

Year |

Total Population |

Population under 14 |

Percent under 14 |

|

1900 |

76.1 |

24.6 |

32.3 |

|

1905 |

83.8 |

26.2 |

31.3 |

|

1910 |

92.4 |

27.8 |

30.0 |

|

1920 |

106.4 |

31.7 |

29.8 |

|

1935 |

127.2 |

31.9 |

25.0 |

|

1945 |

139.9 |

32.4 |

23.1 |

|

1950 |

151.7 |

38.6 |

25.4 |

|

1956 |

168.2 |

47.9 |

28.4 |

The forth column above shows the percentage of children under 14 years old. In 1935, this percentage was quite low, as would be expected because there was a depression on. People could hardly feed themselves or find jobs, let alone start families. In 1945, it was even lower because the young men were still off to war, and the young women were busy making planes and tanks instead of babies, so nobody really had time for families and raising kids during those years. A dramatically different statistic arose after the war. Everybody suddenly wanted to get married and have babies. In 1956 during its high point, the percentage of children shot up to a staggering 28.4 percent. That’s when they began calling it a baby boom, and when we heard stories of capacity difficulties from the statisticians and demographers. And they were right. The big baby boom did come and it did have the predicted consequences.

In spite of all the notoriety surrounding this baby boom, however, the percentage of children in the general population was not the highest in U.S. History. More precisely, the proportion of kids around 1900 was 32.3 percent. That’s four percent more than during the great earth-shaking baby boom of the fifties and sixties. These figures seem to be saying that we may have had a much greater baby boom around the turn of the 20th century and never even paid much attention to it because people were used to seeing lots of kids around.

Statisticians may reject the suggestion of a first baby boom at that time. They point out that there has been a trend since colonial times from large families to smaller ones. They note also that in any post-industrial world, as the standard of living improves, family size decreases. They reason that the high figures during 1890 and 1900 merely represent a continuing trend toward smaller families that began 100 years earlier, and that there was no sudden and unexpected increase in the birthrate at all. Moreover, they argue that the only real baby boom occurred after the Second World War, because it was a true exception to the continuing trend toward smaller families.

The reasoning often given to explain the baby boom after WWII goes something like this:

Long and lonely periods of separation from home.

Desire on the part of many fighting men to forget the war and plunge into the task of parenting.

Compensation for the loneliness and horror of war.

Government support and encouragement for families through the GI Bill as well as aid to injured and disabled veterans.

Increased production and availability of consumer goods as American industry switched from its massive wartime footing. Such abundance following on the heels of wartime deprivation created a strong environment for family development.

I have also heard natural balance tries to compensate for so many people lost to war or catastrophe and to restore the equilibrium by bringing new life into the world. This is a idea first suggested by philosophers of the Middle Ages. These scholars put forth the principle Natura vacuo abhorat (nature abhors a vacuum), which means that nature attempts to compensate for loss of life from war, disease, famine, or other calamity with a corresponding increase in birthrate.

Before the 20th century began, this country did suffer a loss of life -- a huge loss in fact. Without exception, the Civil War was the single worst catastrophe to befall this nation, ever, at any time in its history. In order to understand the extent and magnitude of this destruction, we need only to consider that at least one forth of the white, male, military-age population of the confederacy lost their lives.[3] Although union loses were numerically greater their proportion was not as high because the union had many more people. These figures do not even include the numbers of civilians who died of disease or starvation. Altogether, 4 percent of the entire US population died indirectly because of the war. This represented the greatest loss of life by far of any modern war up until that time or, as some assert, even after.[4] More people and resources were lost during this single war than in our entire history. Add up all the loss of life due to all other wars in which this nation has participated and the total is less than the number of lives lost during the Civil War alone. The amount of property destroyed in the South alone was estimated at two-thirds of the assessed value of the entire Confederacy. At the outbreak of the war, the Confederacy was the third richest country in the world. After the war it had been essentially reduced to third-world status. As Mark Twain described:

…uprooted institutions that were centuries old, changed the politics of a people, transformed the social life of half the country, and wrought so profoundly upon the entire national character that the influence cannot be measured short of two or three generations.[5]

The

misery and suffering caused by this greatest of all American tragedies

can only be estimated. Other

causalities, wounded, missing, prisoners are set at the usual ratio of

three to one, which is probably conservative. That would put the number at about two million people in this

country who were directly scarred

by the war. If we include

all the widows and orphans, the total of those otherwise seriously

affected by the war is about four million, or about one

of every seven people living in the entire country. This represents mostly young and strong people who were lost

forever, the vigorous and energetic of society, the soul and lifeblood

of the country, the future statesmen, adventurers, engineers and

builders, the doers and achievers, all dead, lost to this horrible

war.

The

misery and suffering caused by this greatest of all American tragedies

can only be estimated. Other

causalities, wounded, missing, prisoners are set at the usual ratio of

three to one, which is probably conservative. That would put the number at about two million people in this

country who were directly scarred

by the war. If we include

all the widows and orphans, the total of those otherwise seriously

affected by the war is about four million, or about one

of every seven people living in the entire country. This represents mostly young and strong people who were lost

forever, the vigorous and energetic of society, the soul and lifeblood

of the country, the future statesmen, adventurers, engineers and

builders, the doers and achievers, all dead, lost to this horrible

war.

And there were also the lingering effects of the war, maimed, injured, sick, widows, orphans, mentally scarred, who remained behind long after the last cannon ball was expended, the last saber sheathed and the last musket holstered.

Celebrating heroism, people often forget the hidden ongoing price of pain that ceases only with the death of the last maimed veteran or his widow.[6]

All this dreadful warfare had its effect on the population growth, which is based on three things: births, immigration, and longevity. The Civil War affected all of these.

How then did the Civil War affect population growth? The table below shows population for the years 1850 to 1970 again taken from census data. The percent column calculates the relative change in population that occurred between each ten-year interval. The census figures for 1850 and 1860 are adjusted here to include approximately 4 million freed slaves who were not enumerated in the census until 1870.

|

Year |

Percent Increase |

Population |

|

1850 |

0.30 |

27.2 |

|

1860 |

0.29 |

35.4 |

|

1870 |

0.12 |

39.8 |

|

1880 |

0.25 |

50.1 |

|

1890 |

0.26 |

62.9 |

|

1900 |

0.20 |

75.9 |

|

1910 |

0.21 |

91.9 |

|

1920 |

0.15 |

105.7 |

|

1930 |

0.16 |

122.7 |

|

1940 |

0.07 |

131.6 |

|

1950 |

0.14 |

150.6 |

|

1960 |

0.19 |

179.3 |

|

1970 |

0.13 |

203.3 |

If

we were to draw a graph that shows years at the bottom and the

rate of change in population growth on the vertical scale, it would

look like this:

If

we were to draw a graph that shows years at the bottom and the

rate of change in population growth on the vertical scale, it would

look like this:

Notice that the great increase in population growth in 1890 was not the continuation of a trend at all, but a sudden and unexpected increase in the birthrate, in other words, a true baby boom just like the one following the second world war, only this first one was bigger percentage-wise.

Rural people generally had larger families because there was a definite need for labor during the few months that crops were harvested. This was a matter of survival. Because labor was hard to come by during harvest time, everybody counted, young and old alike, and the labor of healthy young boys and girls more than paid its way. But in 1870 a big movement to the cities began. Although cities were ill prepared to handle this huge influx of people from the country, the families who left their farms seeking a better life compounded the problem by bringing their children with them.

The rate of growth during this time overwhelmed all existing institutions. A good example of this was the census, which was hopelessly behind in counting it's population.

Then along came Herman Hollerith, a young engineer who

started working

for the US census bureau and realized that things were hopeless. It had taken the census bureau almost ten years to count the

1880 census.[7]

Since it was estimated that the population would grow by almost

13 million by 1890, it was assumed that it was going to take at

least 13 years to complete the 1890 census, three years after the

census of 1900 was to have begun. This would be an impossible situation, so Hollerith invented a

tabulating machine that completed the entire 1890 census in three

years. He later went on to

establish his own computer business, which he named International

Business Machines (IBM).

Then along came Herman Hollerith, a young engineer who

started working

for the US census bureau and realized that things were hopeless. It had taken the census bureau almost ten years to count the

1880 census.[7]

Since it was estimated that the population would grow by almost

13 million by 1890, it was assumed that it was going to take at

least 13 years to complete the 1890 census, three years after the

census of 1900 was to have begun. This would be an impossible situation, so Hollerith invented a

tabulating machine that completed the entire 1890 census in three

years. He later went on to

establish his own computer business, which he named International

Business Machines (IBM).

How accurate were the census numbers? I think the figures were understated, which means there were likely even more kids than the 33 percent reported by the census, an even bigger increase in the birthrate, and therefore a bigger baby boom than the figures show. In 1900 the government simply didn’t have enough manpower to conduct a complete census, and because of the lack of resources to get everyone properly counted, many of the poorer people who had larger families were left out of the census altogether. Besides, many people preferred to remain anonymous anyway because there was a strong mistrust of the government and anyone associated with government. This was especially the case with working people who had bigger families, for they had lots of reasons to mistrust the government.

In

1892 the government violently put down the Homestead

strike and essentially destroyed the union movement in eastern Pennsylvania.

In 1893, union leaders

in New Orleans were actually sent to prison for violation of the

Sherman Antitrust Act. People

felt the government and big business were the cause of the market

crash of 1893 which generated widespread bank closures, wiping out the

life savings of many

poorer

working families. The Pullman

strike of 1894 witnessed federal troops armed with new Winchesters

actually shooting strikers, their own citizens, and Eugene Debs went

to jail simply because he was a labor leader. It is an understatement to say that there was a general

perception in the 1890’s that government and big business were

simply not to be trusted. Therefore,

many of the younger people

who

were first-generation Americans and still were not totally adjusted to

American life were not at all eager to be counted in any census,

especially after the government accidentally destroyed all the

immigration records.

poorer

working families. The Pullman

strike of 1894 witnessed federal troops armed with new Winchesters

actually shooting strikers, their own citizens, and Eugene Debs went

to jail simply because he was a labor leader. It is an understatement to say that there was a general

perception in the 1890’s that government and big business were

simply not to be trusted. Therefore,

many of the younger people

who

were first-generation Americans and still were not totally adjusted to

American life were not at all eager to be counted in any census,

especially after the government accidentally destroyed all the

immigration records.

In the government’s mad-cap attempts to take over the huge increase in immigration and relocate processing to Ellis Island, and amid their frantic efforts to construct adequate facilities, there was a disastrous fire at Ellis Island in 1897 that destroyed all the immigration records as far back as 1855. Such a disaster brought into question the citizenship of well over eight million immigrants and their families who had previously been processed through New York’s Castle Garden. Word got around quickly, and many of the newly arrived immigrants were not especially eager to deal with the government, and in particular a census taker, lest they be expelled or disenfranchised. The government had no way of telling who was legal and who was not since the immigration records before 1897 had, quite literally, all gone up in smoke.

"If

you were in my family I'd punish you."

"If we were in your family we'd punish ourselves." The

Little Rascals.

In

1900 cities were full of kids. At least one-third of the population was under 14 years old.

There was one child for every two adults.

At no other time was there a larger proportion of children in the

population. 1900 was

definitely an unusual time, because society was so heavily and

predominantly young.

In

1900 cities were full of kids. At least one-third of the population was under 14 years old.

There was one child for every two adults.

At no other time was there a larger proportion of children in the

population. 1900 was

definitely an unusual time, because society was so heavily and

predominantly young.

Other conditions existed that may have encouraged an increase in birthrate. By 1890, the United States had experienced 25 years of solid peace and prosperity, and this trend was to continue for another 27 years until the outbreak of World War One. During the period from the end of the Civil War in 1865, until the First World War in 1917, the country enjoyed its longest era of peace in it’s history, 52 years of continuous prosperity, almost zero unemployment, no taxes, and the greatest economic growth ever recorded. There were a couple of recessions and a small war but nothing to stop this continued economic expansion. And so people started having children, and they had many children. Looking at the numbers, it seems impossible that a country of almost 30 million people in 1860 could actually double in forty years. And they did it mostly by having children.

Women were expected to have 10 to 12 kids because a good 30 percent of all their children died from the dreaded triple childhood killers scarlet fever, small pox, and diphtheria. However, because of advancements in medicine, sanitation, clean water, plumbing and other improvements in living and working conditions, more children began surviving childhood. Advances in health care are inevitable after a big war when, overwhelmed by masses of broken humanity, the medical profession is forced to improve techniques. This results in breakthrough procedures. The main beneficiaries of medical advancement after the war were the children; and many more of them lived to see adulthood.

America’s two baby booms developed in completely different environments. The first grew out of 50 years of peace and unparalleled prosperity, rapidly expanding immigration, the rise of the middle class, a movement to the cities, rapid generation of wealth, consumerism, and leisure time.

The results of this first baby boom by 1900 created a huge consumer-oriented society of young people, all sharing the same desires, aspirations, hopes, needs, and wants.

There’s the Argentines, and the Portuguese,

The Armenians and the Greeks

They don’t know the language,

They don’t know the law,

But they vote in the country of the free [8].

One factor that contributed to a tremendous population growth,

although in a smaller way, was immigration. Before 1870, there was relatively little immigration to this

country and most of it was from northern Europe. After 1880,

immigrants started coming from a much wider geographical area. The usual groups from western and

northern Europe came, but many more started coming from Eastern Europe and

the Mediterranean, and they brought with them their languages, songs,

and customs, which, up until that time, were scarcely known in the new

world.[9]

All this added to the mixture of language that was to

constitute American society.

One factor that contributed to a tremendous population growth,

although in a smaller way, was immigration. Before 1870, there was relatively little immigration to this

country and most of it was from northern Europe. After 1880,

immigrants started coming from a much wider geographical area. The usual groups from western and

northern Europe came, but many more started coming from Eastern Europe and

the Mediterranean, and they brought with them their languages, songs,

and customs, which, up until that time, were scarcely known in the new

world.[9]

All this added to the mixture of language that was to

constitute American society.

Even though the volume of people admitted to this country rose quickly between 1880 and 1930, the number of immigrants that actually contributed to the increased population as a whole was not that significant. The US population in 1900 was 76 million. The total of all the immigration figures from 1880 to 1900 was around 5 million people, or about 7 percent. Much more significant in this analysis is that many of these immigrants decided to live in New York, and of these, a high percentage went into the music and entertainment industries.

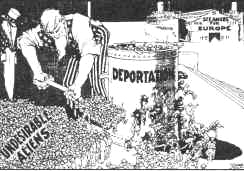

Though they made up a relatively small percentage of the population,

immigrants frightened everybody, even those who had

earlier been immigrants themselves, which included just about

everybody. Citizens were afraid that these foreigners would steal their

jobs, bring in big families, overload the charitable institutions,

work for less, and degrade the quality of life that earlier Americans

had

worked so hard to build up. It

was feared that immigrants would refuse to learn English and fail to

become good citizens, preferring to live on the kindness and charity

of others. There was also

the ever-present fear of anarchists and revolutionaries coming

from other shores, bringing strange ideas and getting involved in

subversive plots to overthrow our government. As we well know, none of this xenophobic nonsense was true.

Instead, the immigrants contributed immensely to the wealth of

this country, particularly to its music.

Though they made up a relatively small percentage of the population,

immigrants frightened everybody, even those who had

earlier been immigrants themselves, which included just about

everybody. Citizens were afraid that these foreigners would steal their

jobs, bring in big families, overload the charitable institutions,

work for less, and degrade the quality of life that earlier Americans

had

worked so hard to build up. It

was feared that immigrants would refuse to learn English and fail to

become good citizens, preferring to live on the kindness and charity

of others. There was also

the ever-present fear of anarchists and revolutionaries coming

from other shores, bringing strange ideas and getting involved in

subversive plots to overthrow our government. As we well know, none of this xenophobic nonsense was true.

Instead, the immigrants contributed immensely to the wealth of

this country, particularly to its music.

I believe there are two basic theories about cultural assimilation. The melting pot theory says that everyone’s culture is mixed into a big mulligan stew and the eventual result becomes sort of a composite American culture, each individual culture adding its little bit to build the American way of life. On the other hand, the mosaic theory says that immigrants retain their own cultural identity within a mosaic, like a huge patchwork quilt, while at the same time contributing to the entire picture. The original culture will continue to survive as an inner layer so to speak, while the outer layer absorbs and manifests the host culture through language, manner, style, etc.

This mosaic theory fell very much out of favor during our two world wars and into the 1950’s, because America was trying to present a solid front against the forces of fascism, communism, tyranny, and any other ideology that could be considered un-American. The spirit of patriotism ran high and everyone was assumed to be cast in the same true, red-blooded American image, all part of this big melting pot. Diversity and independent thinking were frowned upon because “there was a war on.” People were encouraged to forget the ways of their immigrant parents and become baseball-loving, hot-dog-eating, ice-cream-licking, beer-drinking, movie-watching Americans. “Love it or leave it” and “My country, right or wrong” became the boilerplates of Americanism. Using these very words, Theodore Roosevelt himself pronounced death to the mosaic theory. He said that all Americans are to act the same, breath the same air, smoke the same cigarettes, in other words, become the same culture in order to enjoy the rights and liberties of this great and powerful country. He thus proclaimed once and for all “There are no more hyphenated Americans.”

But in the late 1960’s we began to re-examine our roots. Suddenly, with all the renewed interest in cultural sensitivity, the mosaic theory enjoyed a rebirth. It was again fashionable to be hyphenated Americans. People began to appreciate their Old World heritage and many scrambled to re-learn some of the customs and ways and lifestyles of their former countries. The feeling became current that America had abused the immigrants by stripping them of their roots, their native languages, their heritage, their rightful culture, and in some cases even their very surnames were “Americanized” to fit a predetermined mold.

Unfortunately, neither of these cultural assimilation theories is very good at explaining what actually happened in 1900. At that time, the process of becoming an American was very complex and can not be reduced to a simple formula or set of rules. Still, it seems that the greater the difference was between the host culture and the invading culture, the faster the immigrant assimilated. An Englishman may never have assimilated, nor his children. Besides, would he even want to give up his English heritage since life would still be quite maintainable? Yet a Greek or Armenian had to adapt quickly or starve to death; and his children adapted even faster. There were, of course, the underlying cultural values, which often never changed. But in this case the most adaptive of immigrants tended to be the first generation Americans whose parents came from fairly dissimilar cultures. This is exactly the climate that was prevalent in 1900. Many of the immigrants were eager to forsake their old ways and wanted to embrace a new and exciting life here. After all, what did they have to lose, since they were coming from countries where they were, for the most part, no longer welcome? So they did in fact try to forsake much of their old traditions, but were unable to do so entirely. These people included a large number who went into the music business and their contributions subsequently made popular music truly international. Even though there never was a conscious attempt to do this, it happened because these first-generation American songwriters still subconsciously carried with them the values and customs of their countries of birth.

But there is a surprising thing about the people coming from Eastern and Southern Europe. The immigrants that arrived after 1880, were actually better able to adapt to a different culture and way of life than the earlier immigrants had been. These people were more accustomed to cultural change, because they had come from environments that were already in turmoil and rapid motion.

The population movements of the half-century after 1880, from whatever geographical source, were the products of an economy geared to operate across national boundaries. The forces of modernization that industrialized Europe and displaced its peasantry continued with effects similar to those before. But the process now operated on a far vaster scale[10]

Although

many Germans immigrants preferred to move further west to the

“German Triangle” area of St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati, the vast majority of new arrivals remained in the cities.

In fact, they stayed mostly in just one city, New York. Many of them were young,

strong, and optimistic. It

was therefore New York that would have the honor of giving birth to a type of music that was

developed to entertain and amuse this vast collection of old and new

Americans alike. And the

music couldn’t be just American, or Italian, or French, or German or

Swedish, or Greek, or Jewish, or Gypsy. It had to be all of these together.

Musicians had to develop a common mode of communication. The population was unbelievably diverse, yet the music had to

appeal to all segments of the population at the same time. It had to find the common thread.

And it did just that as we shall see.

Although

many Germans immigrants preferred to move further west to the

“German Triangle” area of St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati, the vast majority of new arrivals remained in the cities.

In fact, they stayed mostly in just one city, New York. Many of them were young,

strong, and optimistic. It

was therefore New York that would have the honor of giving birth to a type of music that was

developed to entertain and amuse this vast collection of old and new

Americans alike. And the

music couldn’t be just American, or Italian, or French, or German or

Swedish, or Greek, or Jewish, or Gypsy. It had to be all of these together.

Musicians had to develop a common mode of communication. The population was unbelievably diverse, yet the music had to

appeal to all segments of the population at the same time. It had to find the common thread.

And it did just that as we shall see.

By 1880 New York

was the receiving port for about 80 percent of all

immigrants to this country. The

immigration service had been set up on the southern shores of Manhattan at

The new Ellis Island complex had been formally used by the Navy as an ammunition storehouse, and when the huge wave of people arrived for processing, the US Government was ill prepared for the job, and frantically began to build new structures to accommodate all the immigration activities. Bit in 1897, just before all the new buildings were to be opened, a fire destroyed everything, including all the transferred Castle Garden immigrant records going back to 1855.[12] This loss of immigrant records was one of the biggest misfortunes in our immigration history.

After

the fire, immigration processing was again moved back to the

shores of Manhattan, to the Battery, a complex of armories, where it continued until

So in the period from 1880 to 1910, the city of New York was totally changed in it’s ethnic makeup because of this constant flood of immigrants. Big changes were going on all the time in the city that never sleeps. Immigrants were continually providing new labor for the factories and sweatshops of Manhattan with their seemingly inexhaustible supply of workers. Russian Jews, fleeing religious persecution by Czar Alexander II, brought a flood of Jewish immigrants. Where there had been only a small Jewish community in 1880, by 1910, the census reported that New York had a population of 1.25 million Jews. Many of the Tin Pan Alley musicians and songwriters, vaudeville performers, and Broadway actors and performers came from this select group.

Italians displaced the Irish who had once dominated the building trades and by 1897, 75 percent of construction workers in New York City were Italian. And the work was hard.[13] One young Italian immigrant remarked:

Well I came to America because I heard the streets were paved with gold. When I got here I found out three things; First, the streets weren’t paved with gold; second, they weren’t paved at all; and third, I was expected to pave them.[14]

But

New York didn’t care a bit. The

city put everybody to work, and jobs were always to be had for

those who would work. It

was a time of magnificent growth in an environment of zero

unemployment and near zero inflation. In 1890, the city was a completely different one then what had

existed in 1860. Over a

brief period of 30 years, this slow and pondering society had so

radically changed that anyone going into a time machine in 1860

and

emerging in 1890 would be at a total loss to find a single landmark

that hadn’t changed. The

population had doubled as the ever-increasing streams of European

immigration gave the city the unfinished, exciting quality it still

retains today.[15]

and

emerging in 1890 would be at a total loss to find a single landmark

that hadn’t changed. The

population had doubled as the ever-increasing streams of European

immigration gave the city the unfinished, exciting quality it still

retains today.[15]

Thousands of small businesses established Manhattan as America’s main manufacturing center. In 1890, New York’s 25,399 factories produced 299 different industrial products.[16] Regional manufacturing companies could not compete and were forced to relocate to Manhattan. There were so many kids; young, smart, willing to work. The first baby boomers.

East Side, West Side, all around the town

The tots play ring-rosy, London Bridge is falling down.[17]

Immigration only accounted for about seven percent of the first baby boom, but it made a much bigger contribution to the music industry. Because most of the immigrants who landed in New York were musicians to begin with, they fit right into the music business. And they assimilated with great enthusiasm, mixing their own tastes and cultural values into the music they produced.

To get an idea of the contribution that was made to popular music by these first-generation Americans, I developed a list of composers who were major participants in the popular music industry during the early period from 1892 to 1915. The list includes any composer who had at least one song that sold one million copies. Along with this, I listed their place of birth.[18]

|

Armstrong |

|

NY 1901 |

|

Ball |

1878 |

Ohio |

|

Berlin |

1888 |

Russia |

|

Brooks |

1888 |

Canada |

|

Cohan |

1878 |

Rhode Is. |

|

Dacre |

|

England |

|

Davis |

|

US |

|

Dresser |

1860 |

Indiana |

|

Edwards |

1878 |

Germany |

|

Fisher |

1874 |

Germany |

|

Handy |

1873 |

Alabama |

|

Harris |

1868 |

NY |

|

Herbert |

1859 |

Ireland |

|

Hirsh |

1887 |

New York |

|

Hoschna |

1877 |

Germany |

|

Howard |

1878 |

New York |

|

Joplin |

1868 |

Texas |

|

Kern |

1885 |

New York |

|

Meyer |

1884 |

Boston |

|

Monaco |

1885 |

Italy |

|

Piantadosi |

1884 |

New York |

|

Romberg |

1887 |

Hungary |

|

Schwartz |

1884 |

Hungary |

|

Sousa |

1854 |

DC |

|

Thornton |

1861 |

England |

|

Van Alstyne |

1882 |

Chicago |

|

Von Tilzer, A. |

1878 |

Indiana |

|

Von Tilzer, H. |

1872 |

Detroit |

|

Wenrich |

1887 |

Missouri |

Among

the 29 composers listed here ten were born outside the

United States. This rough tabulation

indicates that around one third of early popular music

composers were foreign born. The percentage of first-generation Americans in the general

population was never higher than 7 percent.

Among

the 29 composers listed here ten were born outside the

United States. This rough tabulation

indicates that around one third of early popular music

composers were foreign born. The percentage of first-generation Americans in the general

population was never higher than 7 percent.

Who threw the overalls in Mrs.

Murphy’s chowder?

Nobody spoke so she shouted all the

louder.

“It’s a dirty Irish trick,

I’ll lick the Mick who threw

The overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s

chowder.”[19]

So with the new century came a variety of popular songs that had never been seen before; the “bird cage” song, The Bow’ry, Bill Bailey, and many other songs that echoed down the streets and alleys of their own city, New York. From all this din came came the slow American Waltzes breezing over apartments and tenement houses on hot summer nights, while the neighborhoods organized street dances by gaslight. There came also the feisty ragtime numbers that scandalized an older generation and caused many a parent to wring hands and seriously wonder what all this wild music would do to the young people. Surely, what can the future be like for these unruly and undisciplined youngsters who actually enjoyed this junk?

Of course, there were too the Italian songs, played to the bounce of the hurdy-gurdy and the accordion, complete with dancing monkeys in little bellboy hats. The lusty, heavy German bar songs generously extolled virtuous heavy beer, while soft Russian ballads, as expected echoed a lifestyle forsaken and forever lost.

Then came irrepressible and boisterous Irish songs from men and women who could out-sing, out-fight, and out-drink just about anybody else -- so many Irish songs; Kathleen, Sweet Rosie O’Grady, My Wild Irish Rose, Harrigan, Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly, Mother Machree and so many more. Never before on earth had such a collection of ethnic diversity lived together in semi-harmony, sharing cultures, drinking beer and wine together, going to the same houses of pleasure, and singing the same songs, weaving it all together into a mosaic of incredible complexity, truly a big chowder with overalls in it.

Another type of immigrant, those who didn’t necessarily come from another country, but who came from hostile environments nonetheless, was represented by black composers, singers, and piano players who all came to New York in search of new lives and a chance to exercise their talents and freedoms. There was James Bland, Bob Cole and the Johnson Brothers, as well as Gussie Davis, Earnest Hogan, and the great piano player Louis Chevin. Of course, Scott Joplin brought his ragtime and W.C. Handy brought his horn. They all came to New York, some sooner, and some later, but they all eventually packed up their music and came.

New York

was the undisputed popular music center of the world, the breeding

ground, the oasis, and it drew people of talent from far and wide.

New York

was color completely blind. At a time

when mixed minstrel shows still could not do the circuit, when white

supremacy still prevailed in many areas, when black people were hanged

for the slightest offense,

New York not only assimilated other music types, it flavored them to its own tastes and desires. One good example was ragtime, because it offered something new to the standard music of the day. In the same way that Rock ‘n Roll gave new life to the music industry in 1955, ragtime infused 1899 popular music. Ragtime may have started in new Orleans, and moved northward along the Mississippi, finally settling in St. Louis where it developed its own style. After that it was copied, refitted, changed, and imitated by the many singing groups, vaudeville acts, touring minstrel shows, and circus bands that followed the Midwest entertainment circuit. When ragtime, with its distinct syncopation got to New York it became something even more exciting. The popular music developed in New York possessed it’s own style, it’s own character; and that character was to become a permanent feature of music. These were the overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s chowder.

To the surprise of just about everybody After the Ball and Daisy Bell both sold over one million music copies in 1892. An unprecedented population increase of 26 million people from 1880 to 1900 made this easily possible. One third of the total population was under 14 years old. That’s 25 million children. These 25 million young people wanted to buy things and would have time to enjoy what they bought. It stands to reason that items include relatively inexpensive entertainment, such as easy-to-purchase sheet music. The consumers were there and the expectations were there and, as we will later see, the pianos were there too. Young people would be the most responsive to the music, and just as it is today, its primary consumers. The need for entertainment, for music, specifically for American music was there. With the quiet emergence of this huge consumer market--mostly young people--along with the increase in recreational time and disposable income, the popular music explosion was certainly ready to happen.

I think the first baby boom was caused by nature righting itself after a cruel and debilitating war. This sudden increase in the younger population created a market for cheep entertainment. Facilitated by a long period of peace and prosperity, this baby boom was augmented by huge volumes of enthusiastic immigrants that were eager to become Americans and who brought along their own special talents and musical contributions. Popular music was one of the unifying threads in a rapidly growing country. Designed to appeal to the largest segment of society, the emerging middle class, it planted the seeds of a common American language, the language of music. American popular music was to become the universal unhyphenated language of America.

Here are some other links in this article:

Origins of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

[1]

James Blake & Charles Lawlor, Sidewalks

of

[2]

Historical Statistics

of the

[3]

James M. McPherson, Drawn

with the Sword (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 66.

[10]

Handlin, 176. Reprinted

by permission.

[16]

Lankevich, 126.

[19]

G. Giefer, Who Threw the Overalls in Mrs. Murphy’s Chowder?,1898.