Minstrelsy

Dominic

Vautier 1/7/2011

The first stage presentations of

minstrel shows occurred as early as 1844, around the same time that

Foster started publishing. Minstrelsy

was a type of musical theater that tended to follow a prescribed format

and use a predefined set of characters. It became very popular just before the Civil War.

The great pioneer in this field was Edwin Christy, who developed

what many considered the standard format. An interesting thing about minstrelsy is that it utilized some of

the basic ideas of Greek Drama. The

blackface and whiteface were masks or “persona” which transformed an

individual into something else, a stage actor. Also, as in Greek drama, women were not allowed to act and the

parts of females were traditionally played by transvested men. As the 19th century wore on, the exclusion of women

began to disappear and it became more common for women to appear in

minstrel shows.

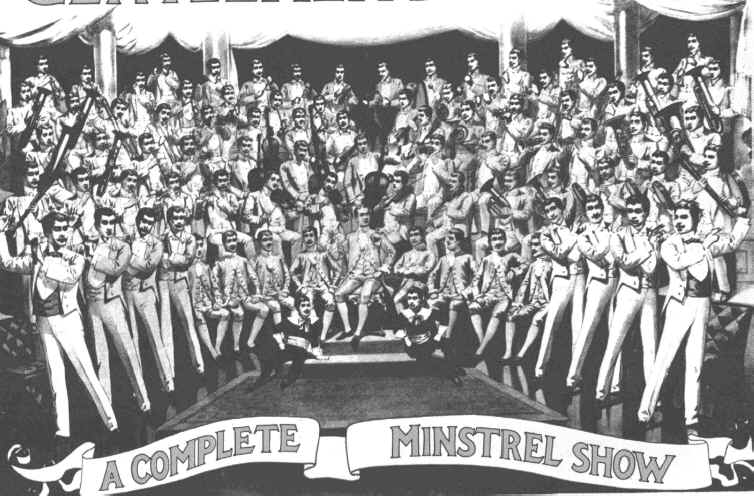

Perhaps the best way to describe the

format of minstrelsy is to run through an actual show. The first part of the performance is called, logically enough, The First Part. The

curtain opens to a rousing number, usually De

Camptown Races, Entry of The Gladiators,

Swanee River

or, more commonly after 1898, Hot

Time in the Old Town Tonight. Minstrels drill back and forth on the stage during this opening song and wind up

in front of their seats just before it ends. The acting troop forms a semi-circle facing the audience and the

interlocutor (in-ter-loc-a-ter)

announces, to a shrill of trumpets, “Gentlemen, be seated.” The show formally has begun.

The interlocutor, or middleman, is

usually in whiteface, well dressed, acts as master of ceremonies, and

controls the general pace of the show. His demeanor is proud, haughty, and condescending, representing

the upper class, businessmen, land owners, and politicians. At the end of both sides of the semicircle of performers are his

arch antagonists, Mr. Bones to his left and Mr. Tambo on his right, so

named because they play bones (castanets) and tambourine, respectively.

These two people, known as end-men, are always in blackface and

are dressed in colorful and often outlandish outfits. They continue through the course of the program to ridicule,

belittle, and torment the unfortunate interlocutor, making all manner of

jokes at his expense. The

interlocutor is slow of mind and manner, and purposely acts as the butt

of all these jokes. By the

way, the jokes are very bad. Here

is an example:

Bones: Mr. Interlocutor,

I’d like to ask you a question.

Bones: Mr. Interlocutor,

I’d like to ask you a question.

Inter: Why certainly. Go ahead Mr. Bones.

Bones: What has four legs and flies?

Inter: You’re not going to pull that old one on me again, are you?

Bones: Why you just don’t know the answer do you?

(laughter)

Inter: Of course I do. It’s a dead horse.

Bones: Wrong, all wrong.

(mild laughter)

Inter: I’m wrong? Well

suppose you tell me then what has four legs and flies.

Bones: Two pair of pants.

(great laughter)

The second part of a typical minstrel show, called the Oleo

or variety show, consists of specialty acts and non-stop comedian

performances, soft-shoe, tap dances, and the like. The third part is called the burlesque

or conclusion, which is a

review or parody of the first two parts. It may be composed of a skit, a farce or a short one-act play.

The early minstrel show

usually consisted of the First

Part, the Oleo, (the variety show), and the Conclusion. The Conclusion

could be a finale, or a short skit, or burlesque satire. This standard arrangement of the parts changed over the next 80

years as minstrelsy evolved. Sometimes

the second and third parts were combined.

Sometimes the burlesque

was skipped. Often there

were many burlesques. Recent research into the playbills (programs) of early minstrel

shows indicates that the structure was even looser than previously

thought.[1]

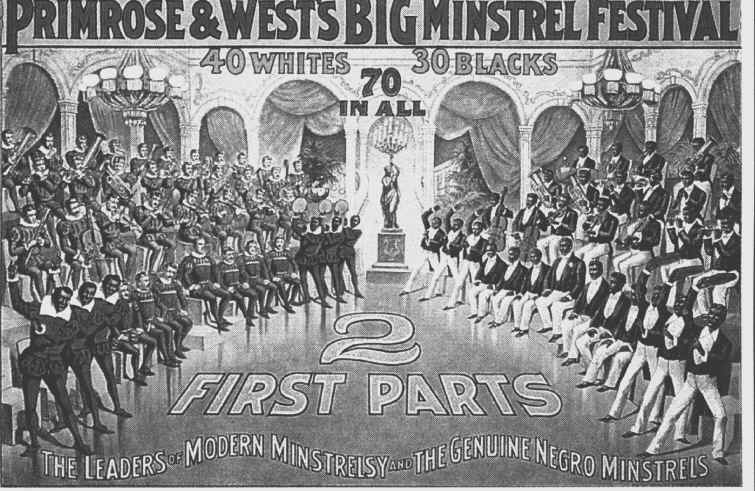

In larger shows there were as many as ten end-men, and even

sometimes two middlemen, one in whiteface and the other in blackface.

Throughout all this evolution and

experimentation, however, the characters of minstrelsy remained much the

same: the middleman (in whiteface, proud, haughty, well dressed, slow of

mind) and the end-men (black-faced wise-guys, smart-alecks, outlandishly

dressed). The end-men

symbolized the common man, that is to say, the audience, and when the

smart-alecks directed their ridicule at class structure, they spoke for

the masses. Common folk felt

that social position, power, and wealth did not reflect essential human

worth, and that all people were equal, in life, in death, and on stage.

Minstrelsy sang the praises of a society without class. It was indeed a classless act.

The blackface motif associated with Minstrelsy was not intended to

constitute a racial put-down that we may be tempted to interpret it today.

Rather, blackface was chosen because it was a powerful way to

deliver satire, something that audiences could readily understand, and

it was practical as well. First

of all, the easiest way to become a different person while on stage was

to assume some kind of disguise, and burnt cork was a cheap and

available commodity. Secondly,

the black tradition offered a stereotype of the quintessential “common

man,” who did not equate wealth or social position with essential

human value. This

stereotypical man in blackface offered the audience a character to

identify with. He was

fun-loving, uninhibited, lazy, and disposed to laugh at the expense of

those who were pompous, haughty, and self-impressed, and the average

folks in the audience were more than glad to laugh along with him.

The inclusion of the stereotypical

black man may well be considered racist in today’s world, but a few

additional things must be kept in mind. First, the character in blackface was a “wise-guy,” and he

was never the butt of the audience’s laughter. He was, instead, the audience’s accomplice in the assault on

class distinctions. Second,

in 1844 ethnic stereotypes were considered fair game. In an era when racial sensitivity and political correctness were

unknown, people accepted the use of ethnic humor as just one more thing

to laugh at. Third, there

was a necessity, just as in Greek drama, for the actors to assume a

stage "persona," that is, the character of an unrecognizable

person while on stage. That

on-stage actor had to be essentially disembodied, completely

disassociated from the actual person who played the part, and this was

accomplished by wearing a "mask." That "mask" was burnt cork.

The effect is similar to the strict rule at Disneyland

that a cartoon character must never, ever, be seen partially out of

disguise because it destroys the illusion.

Minstrelsy was important in the

development of popular music for it became the custodian for much of

Foster’s material, and his tradition played a key roll in the subsequent

development of popular music. After

all, it was Edwin Christy, organizer of “Christy’s Minstrels,”

who purchased and performed many Foster songs. This inclusion of Foster’s music in minstrel performances

preserved and protected his song tradition through the so-called

“dry” years (between his death in 1864, and the beginning of the

popular-music era in 1892). Without

this preservation, the strong influence of Foster’s work on popular

music may have been lost.

For a long time it seams, popular music cast envious eyes on

the minstrel way of singing and even went so far as to develop its own

brand of blackface. Blackface

then became a legitimate subset within popular music to support heavy

syncopation and snappy tempos, techniques that were otherwise not yet accepted in

mainstream music. Irving

Berlin, the Von Tilzer brothers, Al Piantadosi, Fred Fisher, and other

top-rate writers of the period were able to write popular songs in

blackface in order to justify use of catchy rhythms and

syncopations. Also among

these writers was the song-and-dance man Eddie Leonard who absolutely

excelled in blackface. He fell in love with a girl named Ida and

wrote the song Ida, sweet as Apple Cider!.

This song was one of many that well captured the minstrel style.

[1]

William J. Mahar, Behind

the Burnt Cork Mask, (University of Illinois Press, 1999).

Here are some other links in this

article:

Origins

of Early Popular Music

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People

Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

How

Dancing Helped Music

Women

and Early Music

Some

Early Songwriters

Some

Songs

The

Influence of the Piano

Recorded

Music

Sheet Music

Chronicles

1892-1900

Chronicles

1901-1915

Million

Sellers

Bones: Mr. Interlocutor,

I’d like to ask you a question.

Bones: Mr. Interlocutor,

I’d like to ask you a question.