Women and Early Popular Music

Dominic

Vautier 1/7/2011

My

gal is a highborn lady, She’s black but none too shady[1]

Victorian

men had an interesting view of women. They believed, or were somehow led

to believe that women were morally superior and therefore women

had an obligation to act as a spiritually elevating influence. By a

similar logic, men also had too much respect for the “fair” sex to

allow them to get involved in the vulgar details of everyday life,

things like finance, business or politics. [2]

In short:

Victorian

men had an interesting view of women. They believed, or were somehow led

to believe that women were morally superior and therefore women

had an obligation to act as a spiritually elevating influence. By a

similar logic, men also had too much respect for the “fair” sex to

allow them to get involved in the vulgar details of everyday life,

things like finance, business or politics. [2]

In short:

Beautiful

dreamer, wake unto me.

Starlight and dew drops are waiting for thee

[3]

However,

as the 20th century approached, popular music started singing a

different tune. It began to move contrary to everyday thinking and

considered women from a more refreshing perspective. The Victorian beliefs

combined with a European worldview consisted of three k’s, Kuche,

Kirche, und Kinder.[4] This idea was being slowly and

relentlessly replaced in America by a different perception of females in

society.

The

music of the day

reflected that perception, and in some cases, only music addressed the

issues that society at large continued to ignore.

In material that began to appear after 1892, women started to do

outrageous things, they

flirted on streetcars, they rode bikes, they flew in airplanes, they

danced all night, they gallivanted around in automobiles, and worst of

all, they were observed smoking in public. Popular music of

this era reflected these idea that women and men were equally able to have

wild and reckless adventures.

Come

Josephine, in my flying machine

Come

Josephine, in my flying machine

Going up, she goes! Up she goes!

Balance yourself like a bird on a beam,

In the air she goes, there she goes[5]

This

paints a different picture than the standard music before 1892, which

portrayed women as objects of either worship or scorn, or more likely

they were just ignored. Women had been

represented either as the misbehaving female who wandered from the path

of moral correctness and consequently incurred the punishment of a stern

and unyielding social order, or in the role of the stereotype,

as the virtuous heroine who followed the prescripts of society and

reaped an appropriate reward.

We

find that the songs

of the1870’s and 1880’s were quite conservative in their attitude toward

women. In this earlier time the

tendency was to avoid emerging issues facing a society in silent yet

deep underground turmoil. Large numbers of immigrants were being added

to the country, social standards were being recast, and the frontier

was creating an equality. Women, either by choice or by need,

were entering the work force for the first time. So songs of the

1890’s and 1900’s celebrated figures who were able to step out of their

standard stereotype. The songs told of outgoing and adventuresome women

who were not afraid to make their own way and take advantage of

all the exciting opportunities that were becoming available.

Throughout

history women traditionally have had fewer rights than men, but since America

started out as a frontier country the social order was upset. In

Europe, from which at that time we drew much of our culture and customs, no

frontier existed, so they had been relatively stable for

centuries. Even in Colonial America, every effort was made to maintain a

predominantly European way of life, but in America a frontier always

was there to be tamed, and it should be expected that changes were going to

occur. On the frontier, traditional roles were no longer

meaningful or even appropriate. Men and women found that they needed to

rely upon each other in order to prosper, to raise children, and more

often than not, to simply survive. Although

the suffrage movement began in parlors and meeting halls of northwest New York

state, it should be no surprise that its great breakthrough occurred on

the frontier, when in 1879

Wyoming allowed women to vote.

Throughout

history women traditionally have had fewer rights than men, but since America

started out as a frontier country the social order was upset. In

Europe, from which at that time we drew much of our culture and customs, no

frontier existed, so they had been relatively stable for

centuries. Even in Colonial America, every effort was made to maintain a

predominantly European way of life, but in America a frontier always

was there to be tamed, and it should be expected that changes were going to

occur. On the frontier, traditional roles were no longer

meaningful or even appropriate. Men and women found that they needed to

rely upon each other in order to prosper, to raise children, and more

often than not, to simply survive. Although

the suffrage movement began in parlors and meeting halls of northwest New York

state, it should be no surprise that its great breakthrough occurred on

the frontier, when in 1879

Wyoming allowed women to vote.

Some

claimed that the whole experiment in woman’s suffrage would end in

ruination, Naïve and uneducated women would vote for charlatans,

carpetbaggers, and unscrupulous tricksters; that women did not have the

intellectual capacity, emotional stability, or even the desire to

understand and appreciate the workings of government; and that the whole

electoral process would be undermined by such gross foolishness. Of

course, none of this happened. Contrary to what the some predicted,

there was no great earth-shattering revolution in

Wyoming. Nothing happened. Instead, women usually preferred to vote the same way as their men did

and life went on.

The

panic on 1893 resulted in loss of jobs, homes and savings for many

families. It also drove large numbers of women into the workforce for

the first time. One result of all this was that women had disposable

income, income that they were more or less free to spend as they

pleased. This heralded a different kind of consumerism. A whole spectrum

of new products became available, and at the heart of this market was

the woman shopper. Apparel, kitchen appliances, washing machines,

improved sewing machines, canning equipment, player pianos, facial cream

and cosmetics, beauty aids, garter belts, silk stockings, and of gadgets

were appearing in dry good stores and catalogs. These items were

expressly targeted for emerging woman

consumer. They promised her more free time, relaxation, reading, and

recreation, and I may add, the enjoyment of music. Advertisements began to cater to

this consumer segment. The marketing giants of J.C. Penney, F. W.

Woolworth’s and most of all, Sears & Roebuck with their catalogue,

played heavily into this theme--the woman consumer.

As

could only be expected, the songwriters of Tin Pan Alley

picked up on this movement. Songs such as That’s Where My Money

Goes, Wait Till the Sun Shines Nellie, Where Did You Get That

Hat, The

Bird on Nellie’s Hat, Come Take a Trip in My Airship, Daddy Wouldn’t

Buy Me a Bow-Wow, My Money Never Gives Out, Get Your Money’s Worth, In

My Merry Oldsmobile refer directly to the emerging woman consumer.

The Up-to-date Girl

The idea of a “liberated"

woman is nothing new. This was

introduced in several songs

as early as 1896. None states it better than That Up-to-date Girl of

Mine, a song that gained some popularity in Vaudeville but naturally

never left Vaudeville.

You

talk about your maidens with hearts of gold,

Your bleached blondes and dashing brunettes:

But I’ve got a sweetheart that knocks ‘em all cold,

An up-to-date girl you may bet.

She wears flashy bloomers and carries a cane,

She’s a girl you don’t meet every day.

She has plenty of dough and wherever we go,

She will say, “now dear boy let me pay.”

Chorus:

She

bets on the horses At all the race courses, Her equal you never could

find.

This

song remained around for some time. It could almost be labeled

prophetic, considering what was to happen over the next 10 years.

A New York Woman in 1904

Consider

the story of Louis and “Flossie.” Louis’ wife was one of

the 1880 baby boomers, apparently mature, self-confident, and fun-loving

much in the Gibson Girl spirit. [7]

“Flossie” had her heart

set on a trip to

St. Louis to see the world fair but Louis was opposed to the idea probably because

they didn’t have the money or something. So “Flossie” took off on her own and went to St. Louis.

An the song Meet Me in St. Louis, Louis

told it all

Now

Louis came home to the flat,

He hung up his coat and his hat,

He looked all around but no wifey he found,

So he said where can “flossie” be at.

A note on the table he spied.

He read it just once then he cried.

It said “Louis dear it’s too slow for me here,

So I think I will go for a ride.”

chorus:

Meet me in st. Louis, Louis,

Meet me at the fair.

Don’t tell me the lights are shining

Anywhere but there.

We will dance the “Hootchy-kootchy”

I will be your tootsie wootsie,

If you meet me at St. Louis Louis,

Meet me at the fair. [8]

Clothing Styles

Popular

music may have influenced clothing styles. Women consider clothing an

expression of themselves, and this is seen in their recreational habits.

Music and dance started to become an integral part of that expression,

especially in those two key decades surrounding the turn of the last

century, a time which experienced a dramatic increase in both dancing

and singing and where clothing style experimentation was moving at a

high pace. It is hard to separate the clothes women wore from the music

they sang and the dances they enjoyed, for dancing had, by 1905, become

part and parcel of American life.

The

period from 1860 to 1910 witnesses a surprising evolution in women’s

clothing. We can identify at least four different clothing style

changes that occurred just before and leading up to 1910.

The

crinoline period (1850-1870), was marked by the bell-shaped hoop skirt,

which made a woman’s torso appear as if it were emerging from a

flower. This imparted to the wearer a feeling of growth, maturity,

becoming, or emerging. It also accentuated a woman’s lower body and

gave it more importance. The

more exaggerated the dress blossom, the more important she felt. It was

a symbol of her reproductive capabilities.

The

crinoline period (1850-1870), was marked by the bell-shaped hoop skirt,

which made a woman’s torso appear as if it were emerging from a

flower. This imparted to the wearer a feeling of growth, maturity,

becoming, or emerging. It also accentuated a woman’s lower body and

gave it more importance. The

more exaggerated the dress blossom, the more important she felt. It was

a symbol of her reproductive capabilities.

At

first the dress was made to blossom by using many layers of petticoats.

A woman sometimes had to ware as many as 12 petticoats to achieve an

appropriate flowering effect. [9]

Crinoline

dresses were just plain dangerous. Beyond the fact that a slipping

petticoat could cause injury from a fall, many women died or were

seriously burned when they got too close to hearths and open fireplaces

common in homes then. When dresses caught fire there was no easy or

immediately available way to extricate a helpless victim from her many

layers of burning petticoats. So

she died.

Later

in the period, stiff hoops were used to accomplish the same blossom

effect, and these were much lighter and less restrictive. Some said that

the hoop skirt was useful during Civil War times because women could

smuggle ammunition and contraband across the border with impunity. No

decent man would dare search under a woman’s skirt.

The

crinoline period soon went out of fashion and was replaced by the

bustle (1870-1889). Bustles looked ungainly and awkward, and actually

just ugly, but served a vital purpose, functioning as a necessary

transitional device between the more ostentatious crinoline dress and

the less extravagant wasp-waist style that was to soon follow.  The

bustle was scandalous as well as revolutionary. It forced a woman’s

dress to the rear to pretentiously reveal the outline of her waist,

stomach, hips, . and thighs. It also accentuated her rear end and gave a

streamlined and flowing look to her appearance.

The

bustle was scandalous as well as revolutionary. It forced a woman’s

dress to the rear to pretentiously reveal the outline of her waist,

stomach, hips, . and thighs. It also accentuated her rear end and gave a

streamlined and flowing look to her appearance.

Originally the bustle consisted of horse hair and then later of softer

goose down. It actually was quite comfortable to sit on, although a lady

would usually lift her bustle when she sat down or only sit on the edge

of a chair.

The bustle was a curious style, and I can see why it didn’t last very

long. Style changes in those times could be expected to last much

longer, maybe 40 years, but not the bustle. It lasted less than 20

years, and it was completely out of style by 1892. There were still some

bustles advertised in catalogs as late as then, but they were no longer

being sold in stores.

Although we consider the bustle funny-looking and awkward in today’s

world of toothpick figures and long lanky legs, where the emphasis is

more on the upper part of a woman’s figure and the hips, nevertheless,

this fashion was quite appealing to men and considered quite sexy as

well.

The crinoline dress had provided women with a radius of protection, as it

were, an imaginary line of defense beyond which a man could not venture

without violating the accepted norms of decency. Bustles, on the other

hand, removed that barrier, giving men closer access to a woman’s

face, hands, and torso. Not only did it remove this imaginary defense

line, it prepared society for better things, such as close dances and

more physical interactions that would arrive by the end of the century.

By 1892 there was an altogether different look, the hourglass or wasp waist.

It

was quite different in a number of ways. Bodice sleeves became fuller and

puffier, and the dress hemline came up a few inches. The intent however,

was still the same--to emphasize a woman’s sexy shape.

Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately for women’s clothing,

a serious

depression following the panic of 1893, interrupted normal clothing

evolution. Hard times drove many women into the work force for the first

time. But entry of women into the workplace created another situation:

a

demand for more practical clothing.[10]

This may be the reason

why hemlines came up and why working women stopped wearing tight-fitting

corsets. Instead they started wearing a new and quite useful device,

imported from

France, called the brassiere.

Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately for women’s clothing,

a serious

depression following the panic of 1893, interrupted normal clothing

evolution. Hard times drove many women into the work force for the first

time. But entry of women into the workplace created another situation:

a

demand for more practical clothing.[10]

This may be the reason

why hemlines came up and why working women stopped wearing tight-fitting

corsets. Instead they started wearing a new and quite useful device,

imported from

France, called the brassiere.

Corsets of the day encased a woman from armpit to thigh in tight-fitting

fabric reinforced with ribs made of steel or whale bone. This device

forced a woman’s torso into as much of an hour-glass shape as human

flesh could tolerate, and at the same time proceeded to rearrange and

compress her internal organs. An inability to breathe normally was a

common consequence of this fashionable shape, and frequent fainting was

simply dismissed as the “curse of the corset”. Women who worked all

day in fabric shops, at switchboards, in music departments, and at dry

goods’ counters could not be allowed the luxury of fainting every once

in awhile. We often hear stories of women swooning upon the least

provocation. This may have had more to do with the breathing

restrictions imposed by a corset than with the tender sensibilities of

affected females.

Evolving recreational habits for women also dictated clothing changes.

Well-to-do ladies were able to avail themselves of tennis and croquet,

and there was suitable attire for just such occasions. However for the

vast majority of women, recreation was more restricted. There was, of

course, abundant recreation offered by the amusement parks,

nickelodeons, dance halls, and riverboats,

plus strolling, canoeing, and touring. But dancing

became a primary source of recreation, and the more demanding dance

steps consequently required a more agile dancer and therefore a more

relaxed kind of clothing.

The

1890’s saw the beginning of other substantial changes in women’s

clothing. Before the turn of the next century, fashionable women wore

their hemlines down to their shoes. By 1908 hemlines had came up to

just above the ankle. This may not seem like a big deal, but breaking

the ankle barrier was much more important than it might seem, for not

too longer after this hemlines went all the way up to just below the

knee and then even above the knee.

For

many years higher hemlines had represented the lower end of the social

spectrum. In

New York young women who visited from farms in the country wore the higher

hemlines that farm-living dictated. Women who came from Europe

were used to a slightly higher hemline. Photographs and sketches

show some that came up almost to the ankle. These people couldn’t

afford to change clothes as frequently as the well-to-do could for they

had neither the additional clothes nor the servants to clean them. Since

city streets were full of mud and horse manure and in many places

sidewalks were nonexistent, women who worked in shops, sewing mills, and

factories in and around Manhattan

tended to ware their hemlines slightly above the ankles as a matter of

practicality. Well-to-do ladies continued to wear their ‘street

sweepers” below the ankle.

The

new century saw another shift in clothing style called

the Gibson Girl look, which became quite the American and European fashion.

By 1899 the

country was out of depression and abundant employment could be had.

Anyone willing to work got a job. Good times were here once

again. Money was available and it was freely spent.

That’s

where my money goes, to dress my baby,

I buy her everything to keep her in style.

She’s worth her weight in gold, my lovely lady.

Say boys, that’s where my money goes.[11]

This

new look, also called the “s-curve” or the “Gibson bend,”

started with the bodice being pouched forward, the so-called

“pigeon-breast” or “kangaroo pouch.” The bosomy effect was

combined with a tight waistline that forced the hips slightly back,

highlighting the rear end. This combination created the Gibson

“s-curve.” No statistics are available on increases in back trouble

among women during this period, but the exaggerated s- curve had to

cause back problems. But then this was not the

first time in history that human comfort and spinal health were

sacrificed on the altar of fashion.

This

new look, also called the “s-curve” or the “Gibson bend,”

started with the bodice being pouched forward, the so-called

“pigeon-breast” or “kangaroo pouch.” The bosomy effect was

combined with a tight waistline that forced the hips slightly back,

highlighting the rear end. This combination created the Gibson

“s-curve.” No statistics are available on increases in back trouble

among women during this period, but the exaggerated s- curve had to

cause back problems. But then this was not the

first time in history that human comfort and spinal health were

sacrificed on the altar of fashion.

Men’s

styles were less susceptible to change, and about the only things were the

introduction of boat hats, derbies, and slightly different collar

styles. Beards were gone by 1890, mainly through the highly circulated

and influential cartoon work of Charles Dana Gibson and others who

portrayed ideal men as either clean-shaven or sporting a clean mustache.

Newly

urbanized young people forced these rapid style changes, partially

because young people entering this environment brought their own ideas

of dress and behavior, and also, perhaps, because these people did not

feel they were obliged to blindly follow the prescriptions of

their elders.

I think

this all suggests that major cultural patterns can often be

best traced and studied by women’s clothing styles. Fashion is after

all, the closest thing to the people of any period, and the ways of

social change are supported by these clothing styles. By a similar

argument, popular music closely reflected clothing changes. Take the huge hats then in

use by women, The Bird on Nellie’s Hat, Tip Your

Hat to Nellie, and Where did You get That Hat are a few examples.

With

the four major style changes occurring from 1860 to 1900, women had

successfully moved away from a dress style that absolutely prevented fast or

close dancing, as well as intimate social interaction such as kissing

and petting. The clothing styles they preferred were well adapted to

new trends. Women had been

able to emerge from a restrictive Victorian framework and devise

clothing suitable for recreational and social activities that itself became in

fashion at the turn of that century. But of all these changes, none was

more profound and far-reaching than the re-introduction of bloomers.

Bloomers

Early

in 1851 Elizabeth Smith Miller came to visit her cousin Elizabeth

Stanton in Seneca Falls, a small town just south of Syracuse,

New York. She brought along an unusual costume that she had seen during her

travels in

Switzerland. It consisted of a skirt that came down only to the knees, but under

the skirt was a pair of long ballooning pantaloons that gathered tightly

at the ankles. The outfit was immensely practical, and Elizabeth Stanton

immediately made one for herself.

These

two ladies frequently took walks into town, and on one such occasion

their peculiar dress style came to the attention of the local

postmaster, Dexter Bloomer, and his lovely wife Amelia. Amelia, who was

certainly no stranger to the difficulties of woman, was founder of a small newsletter called

The Lily, which was intended to promote women’s rights. She had started

the paper in 1849 in protest after the Tennessee Legislature ruled that

women could not own property since they had no souls [12].

To

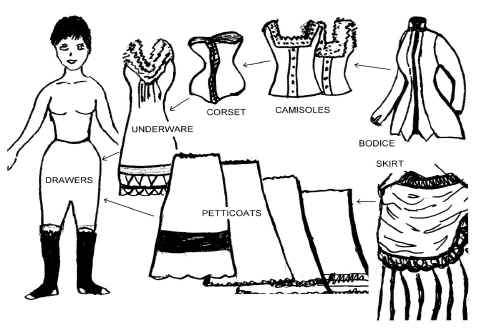

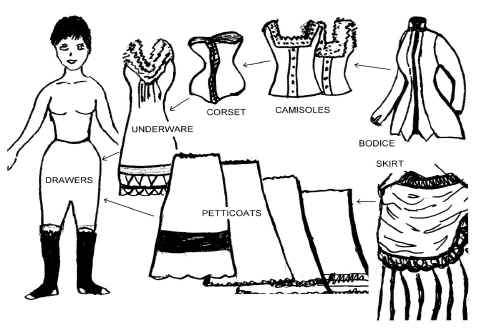

obtain a greater appreciation of the situation, consider women’s clothing of the day.

They wore a tremendous amount of

clothes, which could explain why they were tired all the time. The

typical outfit sometimes included a vast array of skirts and petticoats, and

under all that, a final support petticoat stiffened with circles of

straw, bamboo or steel hoops. There was also a pair of long drawers,

edged with lace. And that was only below the waist.

Dresses

did not come into use until after the turn of the century, so women wore

a tight-fitting bodice above the waist, and under that came one or more

embroidered camisoles. Yet underneath all this was the infamous corset,

sometimes called the “iron lady,” “iron maiden,” or “straight

jacket,” lined with steel or whalebone stays, guaranteed to squeeze

all life and spontaneity out of the unfortunate wearer. Underwear was

warn under the corset (a soft cotton garment resembling a slip), and

finally came a pair of drawers. The weight of all the clothing had

to be enormous, some say as much as 20 pounds [13].

. That’s

close to the weight of today’s fully equipped military soldier in

combat.

This

vast assortment of clothing was worn to church and social gatherings,

oftentimes on hot days, and it became the primary instrument of feminine

Victorian repression.

This

vast assortment of clothing was worn to church and social gatherings,

oftentimes on hot days, and it became the primary instrument of feminine

Victorian repression.

However,

it wasn’t just the shoe-length dress or “street sweeper,” that

wore a woman down. It was the garment itself which was guaranteed to

pick up all sorts of material on the ground, like mud, dog dirt, and

more often than not, excrement from larger animals, and which frequently

had to be washed. Also

whatever a woman was carrying, she had only one hand to do it with

because the other hand was needed to successfully navigate the dress

around obstacles. Other items needed to be carried

such as purses, hand bags, parasols, babies, baby buggies,

handkerchiefs, and baskets of dry goods and groceries as well. One

of the most difficult things to do was to go up a flight of stairs at

night. In order to see the steps a woman had to carry a candle or oil

lamp with one hand and hold up her dress with the other,

which doesn’t leave very many hands for things like babies, laundry,

little toddlers, clothes, food, books, fresh linens, dry goods, etc. A

woman was forced to drape her skirt over the arm carrying the

candle, thus freeing her other arm for things she had to carry, an

awkward and even dangerous situation at best. But the bloomer outfit

made such activities easy. Not only that but the bloomer was practical,

much lighter, easier to keep clean, and actually allowed a woman’s

lower body to breath a bit.

Young and beautiful Amelia Bloomer was quick to see the value of

this garment, and within days had made one for herself. She then

tried to popularize the fashion through her newsletter, The Lily. But

people in her hometown of Seneca Falls, and elsewhere as well, did not at all share her enthusiasm. They

taunted her and threw rocks and eggs at her and her friends every time

they came into town. After all, it may be somewhat tolerable to wear such

atrocious and sinful clothing in the privacy of one’s own home, far away from the public eye, but never

outdoors, and

absolutely never in the presence of men. Men wore pants. Women did not.

God did not intend women to wear pants. This was

clearly stated in the bible.[14]

Young and beautiful Amelia Bloomer was quick to see the value of

this garment, and within days had made one for herself. She then

tried to popularize the fashion through her newsletter, The Lily. But

people in her hometown of Seneca Falls, and elsewhere as well, did not at all share her enthusiasm. They

taunted her and threw rocks and eggs at her and her friends every time

they came into town. After all, it may be somewhat tolerable to wear such

atrocious and sinful clothing in the privacy of one’s own home, far away from the public eye, but never

outdoors, and

absolutely never in the presence of men. Men wore pants. Women did not.

God did not intend women to wear pants. This was

clearly stated in the bible.[14]

Amelia

and her good friends Susan Anthony and Elizabeth Stanton very much

wanted to continue wearing bloomers, but since it created such an

uproar, they decided the suffrage issue was far more important. They

really needed to focus on the one issue instead of being distracted by

other less important ones. So these three women sadly and reluctantly

hung up their bloomers and packed away their knee high skirts.[15]

This

was 1854 and it would take another 40 years before America was finally

ready to allow women to wear something more practical. The movement

for bloomers came back in the strangest of ways. It came by way of a popular song.

The

Bicycle

In

1892 Daisy Bell followed

After the Ball, and

both songs were huge successes.[16] After

the Ball made some social commentary, Daisy Bell was much more effective

because it was a song that actually did something for the

individual woman. It

generated a freedom of movement that she never had before.

Daisy

Bell

was about a bicycle built for two newlyweds, and the song remained

immensely popular throughout the entire decade of the 90’s, selling

several million copies, and lots and lots of bicycles along with them.

The

technology of bicycle design and manufacture had reached a point of

successful marketability. Invention of balloon tires and chain action

had generated a machine that was essentially the same as what we have

today. The bicycle of the 1890’s was a vast improvement over former

awkward and clumsy Three-wheelers

and big-wheelers, and a far cry from the even more ridiculous

wooden-wheeled straddlers of the 1850’s, which could hardly be

classified as bicycles anyway.

Soon

after the time of Daisy Bell's publication, bicycle sales were going

nowhere but up. With the rubber balloon tire, and all the other

ingenious mechanical improvements, such as a smaller spindle size and a

better chain drive, the bike of the middle 1890’s was fit for anybody

to ride even the ladies. The “safety” or “wheel”, as it was

then called, was so popular in both

England

and the United States, that by 1898 there was a bike in almost every household in

America.[17]

Soon

after the time of Daisy Bell's publication, bicycle sales were going

nowhere but up. With the rubber balloon tire, and all the other

ingenious mechanical improvements, such as a smaller spindle size and a

better chain drive, the bike of the middle 1890’s was fit for anybody

to ride even the ladies. The “safety” or “wheel”, as it was

then called, was so popular in both

England

and the United States, that by 1898 there was a bike in almost every household in

America.[17]

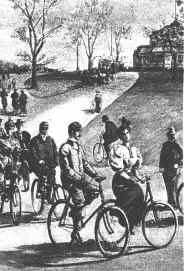

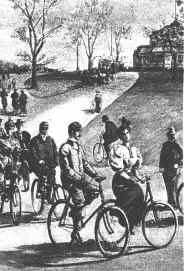

Outside

the racetracks, bicycles seemed to spin everywhere, as the public went

wild for the wheel. The number of Chicago cycling clubs, for instance, swelled from 50 in 1892 to 500 in 1895. By

1897 an estimated one in seven city residents owned a bike.[18] By

1899, an estimated ten million cyclists were on the road.[10] Squadrons

of men and women used the wondrous machine. Bicycle

paths were laid out all over Central Park. By 1900 America

was firmly in the grip of this bicycle

fad.

It also seems that bicycles were turning out to be a great sexual

equalizer. Young

women especially took to the new cycle for here was a rare chance to be

equal to men - and then some. “The ladies have obtained complete

mastery over the wheel,” observed the Country Club of Evanston’s

1895 yearbook, “and it is oftentimes a matter of grave doubt whether a

lady or a gentleman will first reach the destination.”

[20].

Bicycles

may certainly have played a roll in the cultural change that was

occurring over this same period, especially in the perception of a young

woman’s roll in society. Young ladies packed lunches, cast off their

petticoats (synonymous with bra-burning), donned the scandalous riding

bloomers, and went off for a “spin” in the country, unescorted no

less.[21] Sometimes, to the horror and astonishment of parents,

they would be gone all day. Preachers bellowed, and schoolmarms wailed

at the shame, scandal, and turpitude of this invention from the

devil’s very workshop. They claimed the contraption fostered an

out-and-out disregard for any standard of decency and was a clear

affront to the dignity of women. Politicians and churchmen alike used

the social uproar to handily condemn the outrageous conduct of these

obstreperous young “Jezebels.” But this time the young ladies would

not be stoned or egged or tomatoed into submission. They would not again

be forced from the streets in disgrace, or driven back into second-class

citizenship. After 40 years, their time had come. They would proudly

wear the riding bloomer as a true sign of their position in society.

Bicycles

may certainly have played a roll in the cultural change that was

occurring over this same period, especially in the perception of a young

woman’s roll in society. Young ladies packed lunches, cast off their

petticoats (synonymous with bra-burning), donned the scandalous riding

bloomers, and went off for a “spin” in the country, unescorted no

less.[21] Sometimes, to the horror and astonishment of parents,

they would be gone all day. Preachers bellowed, and schoolmarms wailed

at the shame, scandal, and turpitude of this invention from the

devil’s very workshop. They claimed the contraption fostered an

out-and-out disregard for any standard of decency and was a clear

affront to the dignity of women. Politicians and churchmen alike used

the social uproar to handily condemn the outrageous conduct of these

obstreperous young “Jezebels.” But this time the young ladies would

not be stoned or egged or tomatoed into submission. They would not again

be forced from the streets in disgrace, or driven back into second-class

citizenship. After 40 years, their time had come. They would proudly

wear the riding bloomer as a true sign of their position in society.

The

1890s woman on a bike, Marks writes, decided “where she wishes to go

and what she plans to do once she gets there regardless of a male

companion or lack of one [No] other

individual sport seemed to further a woman’s movement more radically.[22].

But

reactionary forces began to mobilize and tried to stem the tide. The

Philadelphia Taggerts Times thundered that cycling led young and

innocent girls to ruin and disgrace. [23]

Soon after this

proclamation, a Chicago schoolteacher was almost fired for wearing her

riding bloomers into the classroom. Many feared that biking would permit

too much independence, that it would make women hard and assertive, that

young women would no longer obey their parents or husbands, that they

could tire easily and not be able to do their expected chores, and that

exposure to direct sunlight would ruin their skin and sensitive

complexions. It was even asserted that the harsh wind would cause

permanent wrinkles or

destroy a woman’s hair, and more

seriously, that riding itself could injure her internal organs so she

would no longer be able to give birth, nurse babies, or fulfill other

marriage obligations. Finally, such independence was likely to lead to

sexual recklessness and depravity, smoking, drinking, fraternizing, and

other wickedness. They only could pity the foolish young women who cavorted around in

public on bicycles with equally foolish young men. God would certainly

punish the evil daughters of Eve who dared transgress moral standards

and customs that the forefathers had so wisely established years ago and

that had worked so well for all these many years.

But

reactionary forces began to mobilize and tried to stem the tide. The

Philadelphia Taggerts Times thundered that cycling led young and

innocent girls to ruin and disgrace. [23]

Soon after this

proclamation, a Chicago schoolteacher was almost fired for wearing her

riding bloomers into the classroom. Many feared that biking would permit

too much independence, that it would make women hard and assertive, that

young women would no longer obey their parents or husbands, that they

could tire easily and not be able to do their expected chores, and that

exposure to direct sunlight would ruin their skin and sensitive

complexions. It was even asserted that the harsh wind would cause

permanent wrinkles or

destroy a woman’s hair, and more

seriously, that riding itself could injure her internal organs so she

would no longer be able to give birth, nurse babies, or fulfill other

marriage obligations. Finally, such independence was likely to lead to

sexual recklessness and depravity, smoking, drinking, fraternizing, and

other wickedness. They only could pity the foolish young women who cavorted around in

public on bicycles with equally foolish young men. God would certainly

punish the evil daughters of Eve who dared transgress moral standards

and customs that the forefathers had so wisely established years ago and

that had worked so well for all these many years.

Tin

Pan Alley was not at all one to miss such a great opportunity, since

fads had always been a good source of material. The bloomer girls were by no means exempt. Lew Dockstader

composed a lyric to the melody of Just About to Fall describing the

exploits of one such bloomer girl who got her bloomers stuck in the

chain.

Did

you ever see a maiden when she’s riding on her wheel?

Did

you ever see a maiden when she’s riding on her wheel?

How she wears

her baggy bloomers that her limbs she may conceal?

As she rolls alonq the

hiqhway at a brisk and lively pace,

Suddenly a look of horror spreads

itself across her face.

Let us pause a minute, stranger — kindly look

the other way.

Sympathy give to that maiden, for I think I hear her say,

“My suspenders they have busted — If I only had a shawl—”

With

both hands she grabs her bloomers for

They’re just about to fall. [24]

But

the forces of opposition were silenced by something much

stronger--capitalism itself. Women cyclists began to be accepted and

even admired. The quick turnaround in American attitudes was the result

of an intensive effort on the part of the bicycle industry. Money was to

be made on this biking phenomenon, so the bicycle industry, which had

accumulated a huge war chest, was not about to sit by and let

conservative elements of society destroy their burgeoning market.

Bicycle companies banded together to wage an extensive marketing

campaign to change public opinion. Advertisements abounded featuring

happy, healthy, fair-skinned Gibson Girls astride one of their

sponsors’ bicycles, often attired in the scandalous riding bloomers.

Sadly,

however, the demise of the bicycle fad came all too soon thanks to

Henry Ford’s Tin Lizzy. By 1905 bicycle production had

suddenly dropped to 250,000, down from a high of

one million per year in the previous decade and only a dozen or so bicycle

companies were able to survive. [25] But the bicycle had served

its purpose well. American women would never be the same

again. They

had tasted the fleshpots of Egypt. [26]

Bicycles which had given

freedom and mobility to them had merely been replaced by something

bigger and better, the automobile.

The

Working Class

The

whole experience of working outside the home was a novelty. Young men

and women were thrown together in a number of new ways. They mingled

freely on streetcars, in shops, department stores, restaurants, parks,

and factories, all without adult supervision. Young people often

flirted, went oft together, made secret dates, and ate lunch together.

On the shop floor, one manager observed, the young men would whoop, cat

call, and make other ungentlemanly noises at their female coworkers. [27]

Women exchanged advice with each other, offered hints to new employees, and in general learned quickly how to comport themselves in a

workplace environment. Young women working in department stores learned

how to dress to attract customers, became familiar with products, and in

most cases worked harder than men to impress their bosses. One

particular attraction for young women, and in fact a rather enviable

position, was working in the music section of a department store. Almost

every department store or dry goods store of any size had an area set

aside for the sale of sheet music, and it was a big attraction for

customers. A sheet music sales girl was expected to play piano well,

demonstrate new and favorite songs, and be fairly knowledgeable about

popular music. Girls who

could play piano well were in high demand, and the pay was better.

Sounds of piano music filling the store was a big attraction for

customers as well.

And

what’s more, when the day was over, lots of adventures were waiting for

the working girl. Excitement was everywhere: dance

halls, amusement parks, pleasure steamers, and nickel movie houses, all

of which offered these young people some respite after a long day of

tedious work at switchboards, sewing machines, and fabric looms. [28]

Social Songs

A

social song is one that in my judgment makes a statement about social

mores. Social songs were not very

common before 1892. But along with the huge commercial market

created during the early popular music era came a type of song that had

not been there before--the social song.

Several

things may have triggered the advent of social music. Just from an

economic standpoint was, increased disposable income,

especially among women, and this money had to be spent somewhere. A working class emerged that contained a higher percentage of women and

tended to be more entertainment oriented. Female attendance at musical

presentations had gone up. Vaudeville and Broadway both experienced

a noticeable increase in female patrons, (accompanied of course by men).

If

we were to compare two songs of relatively similar content and

popularity, each published at different times before and after 1892,

such as I’ll Take You Home Again, Cathleen (1876) and

Bedelia (1903)

we notice a striking difference in the rhythm, flavor

and tone. The first is quietly reserved, in the Foster tradition, modest, unassuming, and

passive. The newer song is passionate, sexy, linguistically unrestrained

and very assertive. In the case of the songs Silver Threads Among the

Gold (1873) and Put On Your Old Gray Bonnet (1909), both dealing with

problems of aging, the difference is even more striking. One is solemn,

celibate, stern, reserved, reverent, and religiously accepting impending

death. The other is happy, upbeat, fun, relaxed, aggressive, and looking

for great things in the future. These are only a few examples of the differences that existed in the music of these two periods.

It

is difficult to quantify the impact of social music, and even more

difficult to assign or even establish relationships to actual events.

However it is possible to detect themes in the music that either

reflected the realities that were emerging or attempted to encourage

popular trends. We do know that Tin Pan Alley always managed to closely

ride the waves of fashion and fad. Sometimes the music may have even

introduced social trends.

Songwriters

of the day were people supremely observant of the times, who eagerly

wrote about emerging fads, trends, social patterns that they saw and

heard, and actual events and situations that they felt consumers could

understand and relate to: these were the writers of social songs.

Lots more Social Songs

From 1880 to 1915

I picked about

80 songs that were from the years between 1880 and 1915. The songs

were picked because they were popular and because they made social

comments. Some songs (e.g. Down went McGinty, Throw Him Down

McCloskey, The Bow’ry, although popular, are not included because they are

novelty songs that offered little by way of social comment. Each of the

chosen songs was rated on its relative social importance on a

scale from 1 to 10. If a song had serious content we used it,

1. Had serious impact on or reflected cultural trends. (Daisy Bell

freedom through

bicycles, Meet Me Tonight in

Dreamland, sexual

freedom)

2 Made a clear social statement. (Mansion of Aching

Hearts, prostitution)

3. Described a trend or change in custom that was

going on (Elsie from Chelsea,

trolley romance)

4. Ofered insight into new movements in society.

(Ever/body’s Doing

It, new way to dance)

Prostitution

On

February 14, 1892, Rev. Parkhurst ascended the pulpit of Madison Square

Presbyterian Church, just as he had done continuously for the last 12

years, to again deliver his weekly diatribe against the sins of the

Tenderloin. The Tenderloin was an area of Manhattan, bound on the east and west by

6th and 8th Avenues and on

the north and south by 14th and 32nd Streets. It was a more or less

continuous collection of taverns, brothels, and beer halls. The name

came about because police who worked that district were reimbursed

handsomely by local merchants to maintain a hands-off policy and to

engage only in scheduled raids that did not interfere with ongoing

business. There was money to be made on both sides; but still, some

people were offended at the complacent acceptance of prostitution.

But

on this particular day, there sat in the congregation a young reporter

who actually took Rev. Parkhurst seriously, and his sermon was splashed

all over the front page of The New York World. The expose caused such a

stir that the suddenly outraged citizenry of New York

threw out Tammany Hall [29] in 1895 with the election of William

Strong, a conservative reformer. As it turned out however, New Yorkers

weren’t all that happy with reform. They liked

it better the old way, so in 1897 Strong was voted out and replaced by

another Tammany Hall puppet, whose mandate was to leave the Tenderloin

alone.

But

on this particular day, there sat in the congregation a young reporter

who actually took Rev. Parkhurst seriously, and his sermon was splashed

all over the front page of The New York World. The expose caused such a

stir that the suddenly outraged citizenry of New York

threw out Tammany Hall [29] in 1895 with the election of William

Strong, a conservative reformer. As it turned out however, New Yorkers

weren’t all that happy with reform. They liked

it better the old way, so in 1897 Strong was voted out and replaced by

another Tammany Hall puppet, whose mandate was to leave the Tenderloin

alone.

Taken

from The Poilce Gazette entitled “

Gotham

’s Palaces of Sin”, this picture reveals a scene of debauchery and

lustful pleasure.

Taken

from The Poilce Gazette entitled “

Gotham

’s Palaces of Sin”, this picture reveals a scene of debauchery and

lustful pleasure.

More

prostitution occurred during Victorian times than most other periods in

modern history. In fact, the industry reached a high point around 1890. One of the main reasons for this marked increase in

prostitution was a Victorian attitude that happily married women were

not supposed to enjoy sex, that sex was nothing more than an

inconvenient obligation, and that a wife had to “endure it” in order

to have children. Sex as enjoyment did not exist in this context, so

young girls about to become wives were told to behave in bed in a

tolerant yet very indifferent way. Add to this the natural fears of

young girls who had been discouraged from any type of “improper’

behavior since youth, and it could be expected that their

sexual performance was very much like cold fish in a freezer.

In

addition, according to moral dictates of the times, women were

absolutely forbidden to have sex during pregnancy or menstruation.

Therefore, even if a young man was lucky enough to

find a companion who wasn’t intimidated by her strict upbringing,

he was still likely to lose out to old wives tales and the difficulties

of birth control. After all, many wives became pregnant soon before or

after marriage, and the vital joy of newlywed sexual discovery was often

removed from the marital equation, sometimes never to return.

Because

of this folklore, the frequency of sex was probably about once a month,[30]

so middle-class husbands were just plain sex starved. Therefore young men who were otherwise loving and caring toward their

families sought out the services of reputable brothels and women who

were forthcoming, enthusiastic, and accomplished in their sexual

abilities because these men were quite literally unable to enjoy sex

with their wives.

There

were three kinds of prostitutes: call girls, ladies of the brothels,

and streetwalkers. A call girl, or dollymop, was often set up in an

apartment as a mistress to some rich man. She was usually gifted and

well educated. She was required to provide service to her benefactor

and be available at his behest, but often she earned additional money

on the side. In 1900 Harry Von Tilzer wrote the popular song

Bird in a

Gilded Cage about this type of kept woman, something entirely remarkable in that day

and age. He almost got away with it, but had to bow to convention to

get the song published. So he added a line that suggested that the

girl in the gilded cage was “respectably” married. Many if his

contemporaries, however, understood the true intent of the song.

By

far the most common type of prostitute was the “lady of the

night,” who lived and worked in a brothel. She was under the

supervision of a madam. Brothels were very popular in America,

especially among the emerging middle class. Women who worked

there had some degree of security, and the customers who frequented a

reputable brothel could be reasonably assured that they would receive

good value for their money and that the girls were free of disease.

Songwriters

of the day worked in an area of New York near the Tenderloin, and

undoubtedly sympathized with the difficulties of these young women. By

1902, Harry Von Tilzer’s reputation was so great that he was able to

make still bolder social commentary in song and this time had no trouble

getting it published. Mansion of Aching Hearts was a story describing the plight of just such a lady living in a

brothel.

Streetwalkers

were the down and out, the condemned women of society, those who had no

place to work their trade and would usually service their customers in

doorways and back alleys. They often carried venereal disease, which

disqualified them from working in respectable establishments. She

Is More To Be Pitied Than Censured tells of the plight of such a fallen lady and the shame that accompanied her

condition.

She

is more to be helped that despised

She

is only a lassie who ventured

On

life’s stormy path ill advised.

Do

not scorn her with words fierce and bitter,

Do

not laugh at her shame and downfall:

For

a moment just stop and consider,

That

a man was the cause of it all. [31]

Politically Incorrect

In

the days of early popular music, songwriters were experimenters. For

the first time songs contained somewhat honest dialogue between the sexes about

romantic and even sexual topics. To

us the lyrics seem awkward, childish, and even stupid, but in

1900 it was all hot and exciting stuff. Here are a few of my favorite

politically incorrect phrases:

1. If you refuse me, baby you lose me, then you’ll be left alone

(Hello, My Baby).

2. But some day you will come back to me, and love me tenderly (Good-by,

My Lady Love).

3. Come to me my melancholy baby (My Melancholy Baby).

4. It’s sad when you think of her wasted life, for youth cannot

mate with age (Bird in a Gilded Cage)

5. I know I’m to blame. Ain’t it a shame (Bill Bailey)

6. Cause you got another papa on the Salt Lake line (Casey

Jones).

7. My heart’s acting strangely (I’m Falling in Love With

Someone)

8. From temptations, crimes, and follies, villains, taxi-cabs,

trolleys (Heaven Will

Protect the Working Girl).

9. I have a daughter who is hungry for love (He had to get

under and Fix Up His Automobile)

10. Sound of kisses floating on the breeze (By the Light of the Silvery

Moon)

Ways to Meet

The

art of romantic sweet talk by telephone never went out of style, but continues unabated to this

day with social networks, cell phones, e-mail, and tweets. Songs

of the day presented of cleaver ways that young men and women

were able to meet no the "wire'.

Your Girl to the Movies) or go to the many amusement parks (Meet

Me Tonight in Dreamland), or take a ride in an airplane, (Come

Josephine, in My Flying Machine), or, more likely, go for a spin

in an automobile. Songs made extensive use of the car such as In my Merry

Oldsmobile.

But

by far, one of the most common ways for men and women to initiate and

carry on romantic dialogue was the telephone, and by the turn of the

20th century there were many, many telephone songs around. Some

researchers have put the count at well over 100, the most popular of

which was Hello, My Baby.

I’ve got a little baby

but she’s out of sight

I talk to her across the telephone.

I’ve never seen my

honey,

But she’s mine all

right,

So take my tip and leave this gal alone.

Every single morning you will hear me yell,

Hey

central, fix me up along the line.”

She connects me with

my honey, then I ring the bell,

And this is what I say to

baby mine.

Hello,

my baby.

Hello,

my honey

Hello,

my ragtime gal.

Send

me a kiss by wire.

Baby my

hearts on fire.

If you refuse me,

Honey you loose me

Then

you’ll be left alone.

So Baby telephone

And tell

me I’m your own [32].

Perhaps

one of the most artistic and successful of all telephone songs occurred

some years later in 1924 with Berlin’s haunting melody All Alone. .[33]

Here is McCormack singing All Alone.

Just like

a melody that lingers on,

You seem

to haunt me night and day.

I never

realized ‘till you were gone,

How much

I care about you.

I can’t

live without you.

All

alone, I’m so all alone.

There is no one else but you.

All alone, by

the telephone,

Waiting for a ring, a ting-a-Iing.

All alone in the

evening

All alone feeling blue,

Wondering where you are,

and how you

are,

and if you are all alone too.

Some

Ideas

America’s

love affair with popular music started with After The BalL The

song deals with a case of avoidable misunderstanding, because an

intolerant man refused to deal with an obviously embarrassing

situation. Men were not supposed to do that anyway, at least not under

Victorian rules. The man behaved appropriately according to existing

standards of behavior, but to his

utter and complete ruin.

In

brief: This old man tells a story to his niece about a beautiful woman

he had once taken to a dance. He had gone to get her a glass of water,

and as he was returning, saw her in the arms of another man (who,

unknown to him, was the woman’s brother). Full of anger and disgust, the young man left her,

never to see her

again, and she died of a broken heart (for she loved him deeply).

Years later, he discovered the awful truth and had to live with .

We

see here that older standards of conduct, especially concerning

romance, simply no longer worked. The obvious action in this case

would be to confront and immediately resolve things, but the

teller of this tale could not do this because he was unable to unbend.

To let his hurt be known would be to expose that he was vulnerable,

and in need of reassurance. He could not stand the thought of seeing

himself as a supplicant. Some of this aversion to doing anything that

could be interpreted as beseeching is reflected in Robert Browning’s

poem, My Last Duchess. [35]

After

the Ball is different from other tearjerkers. It moves through

three

stages: confusion and anger, sorrow of loss, and then penance

and reparation. The confusion when the man sees his girl with someone else, the sorrow when, years later,

he realizes how ridiculous his

reaction was (which was behaving like any Victorian male was supposed

to), and finally penance when, as an

old man, he reveals his soul to his young niece (which is not

Victorian at all). None

of the tearjerker material of this period can be taken lightly, ror it

represented the seeds of torch music and country music themes that

developed 50 years later, much of which was based upon this same cycle

of sin, loss, and repentance.

Elsie

Following

his big hit Daisy Bell,

Harry

Dacre came through again with

the song Elsie from Chelsea{shall-see).

It is a story of two

People

who meet while riding on a streetcar. A young man gives Elsie his seat

and they begin a conversation. He soon falls hopelessly in love with

this sweet flower of youth. He takes her to an expensive café, spends

all his money, and they romance away the evening. He and Elsie later

get married.

Written

in 1896, the song describes ordinary American people doing ordinary

American things. This was the beginning of “Love American

Style,” even though Dacre was English and the song was originally placed in a section of London. It still demonstrates that

there was a rapidly changing value system and that popular music

was closely following what was really going on. It shows that

the old customs of meeting and being

properly introduced were no longer practical in American society as

class destination was

rapidly disappearing.

Sal Babe

The

song My Gal Sal presents a woman who stands for the ideal female image, the

Gibson Girl: a girl who is loving, caring, and at the same time

independent, rebellious, athletic, and outspoken. Yet she is not a

suffragette, because she feels that true independence can be gained in

other, less ostentatious ways. The song sets up an achievable standard

for women, and suggests that they don’t necessarily have to do wild

and flamboyant things to obtain equality. Instead, kindness and an

ability to council are the true ways to political, economic, and

sexual equality.

They call her frivolous Sal,

A

peculiar sort of a gal,

With a heart

that is mellow,

An all round good fellow,

Is my old

pal.

You’re troubles, sorrow, and

care

she

was always willing to

share

A mild sort of devil,

but dead on

he level is my gal sal.

With My Honey I’ll Croon love’s Tune

By

the Light of the Silvery Moon is

an example of sexual freedom. It is an instance of independent and unchaperoned courtship. By 1909, Americans had begun to

accept the dangerous and revolutionary custom of unescorted dating,

along with its predictable consequences.

In

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, an ex-boyfriend laments because

his girl has just left him and is going with somebody else. In the song

he says, “I wonder if she ever

tells him of me?” Women were not only becoming free in their affairs

of heart, but they were even willing to openly discuss these things--a

big Victorian no-no.

Wait

Till the Sun Shines Nellie describes

a intimate exchange between two newlyweds (or lovers). The woman

expresses her extreme pleasure on her man’s decision to go to Coney Island even though it may rain. This was

a

very forward type of intimacy.

“How I

long,” she sighed, “for a trolley ride

Women could meet men without introduction, and in all kinds

of

settings: streetcars, dance halls, and emerging communication

media.

a. Elsie from

Chelsea (trolley

or bus).

b. Daisy Bell (interesting

way to honeymoon)

c. Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland (rendezvous in an- amusement park).

d. Hello, My Baby ( telephone).

e. Come Josephine, in My Flying Machine (airplane)

f. My

Merry Oldsmobile (car).

Men could describe their inner feelings about women.

a. I Wonder

Who’s Kissing Her Now.

b. Goodbye,

My Lady Love.

c. You Made

Me Love You.

d. My

Melancholy Baby.

e. All Alone.

f. As the car sped on its way,

And she whispered low, Say

you’re all right, Joe,

You just won my heart today [37]

Other

examples in popular songs of the day that reflect a world

in change where standards of romantic behavior

were being redefined.

a. My Wife Has Gone to the Country.

b. Gypsy Love Song.

c. Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland.

d. Shine On Harvest Moon.

e. Take Your Girlie to the Movies.

f. By the Light of the Silvery Moon.

g. Row, Row, Row.

h. My Sweetheart’s the Man in the Moon.

Heaven Will Protect the Working Girl.

Songs before 1892

observed older notions of a woman’s proper place: caring for the young,

cooking,

and church-related activities. There was a

clear demarcation between right and wrong, what was expected of a woman

and what was not.

But songs beginning soon after 1892, began to represent entirely different and

sometimes very

confusing standards for women. With bloomer girls and Gibson Girls

came songs of a bolder sort; and still later,

after 1910,

popular music promoted even a higher

level of emotional and

romantic independence: Let Me

Call You Sweetheart,

Moonlight Bay, My Melancholy Baby, Hello Frisco, You Made me Love You,

Marietta,

and Oh, You Beautiful Doll

all presented images of women who were

able to feel and act independently. As

the popular music period evolved from its big start in 1892, women

were for the first time recognized as a significant part of

society. Popular songs lost their high minded

condescension and nebulous unworldly qualities. Women suddenly begun to be reshaped by the music they sang and danced to.

Songs about woman involved modern

technology. The bicycle and the car put women in a position never before

attained, and all this to reinforce, and

solidified their struggle to attain voting

rights. In 1892 only two states

had

ratified state-wide and local suffrage for women. By 1915 many states had passed suffrage rights for

women, until by the end of the First World War, the l9th amendment

brought universal suffrage.

What

part then did popular music play in all this? There is no real way to measure

the effect of

a constant diet of these “social songs” on a male-dominated country, but I suggest it had

more effect than meets the casual eye. The idea of women’s rights

involved shifts in public attitude. This may have been

accomplished gradually over a period of many years, and the message of

popular music beginning as early as 1892 certainly continued to

reinforce this notion. Songs of the time did reflected a growing interest in

personal relationships, and with personal relationships comes equality.

Suffrage was, after all, a logical consequence of this spirit of

equality that had for years been

strongly promoted by popular music.

Is

bicycling bad for the heart?

Charles Dana Gibson,1897

Here are some other links in this

article:

Origins

of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People

Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

How

Dancing Helped Music

Some

Early Songwriters

Some

Songs

The

Influence of the Piano

Recorded

Music

Sheet Music

Chronicles

1892-1900

Chronicles

1901-1915

Million

Sellers

1 Barney Fegan, My gal is a High

Born Lady, 1896 (the first popular ragtime song).

2 Reay Tannahill, in History (Stein & Day, New York, 1980), 389.

3 Stephen Foster, Beautiful

Dreamer, 1864.

4 In German, cooking, church, and children were the traditional

responsibilities of a woman.

5 Alfred Bryan & Fred Fisher, Come

Josephine in My Hying Macnine, 1910.

6 G. Kennedy and R. Hanch, That

Up-to-date girl of mine, 1896.

7 The Gibson girl was a figure created by cartoonist Charles Dana Gibson.

She was characterized as independent, mature, friendly, athletic and

charming.

8 A. Mills & Sterling

, Meet Me in St. Louis Louis, Louis 1904.

9. Diane Snyder-Haug, Antique

& Vintage Clothing (Kentucky: Collector Books, 1997), 9.

10 Snyder-Hang, 35.

11 Lilly and Daniels, that’s

Where my Money Goes, 1901.

12 Miriam Gurco, The Ladies of Seneca Falls (New York: MacMillanPublishing Co., Inc.), 146.

13 Gurco, 143.

14 “A woman shall not

put on that which pertaineth unto a man”. Deuteronomy, 22:5.

15 Gurko, 144.

17 Census

figures show that there were about 12 million families at that

time. There were at least that many bikes on the road.

18 Crown and Glenn Coleman, No

Hands, (NewYork, Henry Holt& Co., 1996), 18. @ 1996 by Judith

Crown and Glenn Coleman. Reprinted by permission.

19

Crown &

Coleman, 18.

20 Crown & Coleman, 20.

21 Crown & Coleman, 20.

22 Crown & Coleman,20

23 Crown & Coleman, 20.

24 Douglas

Gilbert, Lost Chords: The

Diverting Story of American Popular Songs (New York: Cooper

Square Publishers, Inc., 1942), 215.

25 Crown &

Coleman, 23.

26

To be exposed

to improved living conditions. When Moses left Egypt, some Israelites remained behind because they had become used to

comfortable Egyptian living.

27

John D’Emilio

and Estelle B. Freedman, Intimate

Matters: A History of Sexuality in America (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988), 194.

28 D’emilio and Freedman, 195.

29 Tammany Hall refers to the Democratic Party machine that

controlled New York for many years.

30 The

History of Sex, The History Channel, Aug 17, 1999, Dir. Melissa

Jo Poltier, Ed. Diana Freidberg.

31 Thomas Gray, She is more to be pittied than censured, 1894.

32 Joe Howard, hello, my baby, 1899.

33 All Alone sold 2 million records and 1 million in sheet music.

34 Irving Berlin, All Alone, 1924.

36 Paul Dresser, my gal sal, 1906.

37 A sterling & Harry Von Tilzer, wait till the sun shines Nellie,

1902.

38 ”Then

then there would be some stooping; and I choose never to stoop” from

My Last Douchess reflects an attitude that men could not reveal their inner emotions for

fear of showing weakness.

Victorian

men had an interesting view of women. They believed, or were somehow led

to believe that women were morally superior and therefore women

had an obligation to act as a spiritually elevating influence. By a

similar logic, men also had too much respect for the “fair” sex to

allow them to get involved in the vulgar details of everyday life,

things like finance, business or politics. [2]

In short:

Victorian

men had an interesting view of women. They believed, or were somehow led

to believe that women were morally superior and therefore women

had an obligation to act as a spiritually elevating influence. By a

similar logic, men also had too much respect for the “fair” sex to

allow them to get involved in the vulgar details of everyday life,

things like finance, business or politics. [2]

In short: Come

Josephine, in my flying machine

Come

Josephine, in my flying machine Throughout

history women traditionally have had fewer rights than men, but since America

started out as a frontier country the social order was upset. In

Throughout

history women traditionally have had fewer rights than men, but since America

started out as a frontier country the social order was upset. In

The

crinoline period (1850-1870), was marked by the bell-shaped hoop skirt,

which made a woman’s torso appear as if it were emerging from a

flower. This imparted to the wearer a feeling of growth, maturity,

becoming, or emerging. It also accentuated a woman’s lower body and

gave it more importance. The

more exaggerated the dress blossom, the more important she felt. It was

a symbol of her reproductive capabilities.

The

crinoline period (1850-1870), was marked by the bell-shaped hoop skirt,

which made a woman’s torso appear as if it were emerging from a

flower. This imparted to the wearer a feeling of growth, maturity,

becoming, or emerging. It also accentuated a woman’s lower body and

gave it more importance. The

more exaggerated the dress blossom, the more important she felt. It was

a symbol of her reproductive capabilities. The

bustle was scandalous as well as revolutionary. It forced a woman’s

dress to the rear to pretentiously reveal the outline of her waist,

stomach, hips, . and thighs. It also accentuated her rear end and gave a

streamlined and flowing look to her appearance.

The

bustle was scandalous as well as revolutionary. It forced a woman’s

dress to the rear to pretentiously reveal the outline of her waist,

stomach, hips, . and thighs. It also accentuated her rear end and gave a

streamlined and flowing look to her appearance. Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately for women’s clothing,

a serious

depression following the panic of 1893, interrupted normal clothing

evolution. Hard times drove many women into the work force for the first

time. But entry of women into the workplace created another situation:

a

demand for more practical clothing.

Unfortunately, or maybe fortunately for women’s clothing,

a serious

depression following the panic of 1893, interrupted normal clothing

evolution. Hard times drove many women into the work force for the first

time. But entry of women into the workplace created another situation:

a

demand for more practical clothing. This

new look, also called the “s-curve” or the “Gibson bend,”

started with the bodice being pouched forward, the so-called

“pigeon-breast” or “kangaroo pouch.” The bosomy effect was

combined with a tight waistline that forced the hips slightly back,

highlighting the rear end. This combination created the Gibson

“s-curve.” No statistics are available on increases in back trouble

among women during this period, but the exaggerated s- curve had to

cause back problems. But then this was not the

first time in history that human comfort and spinal health were

sacrificed on the altar of fashion.

This

new look, also called the “s-curve” or the “Gibson bend,”

started with the bodice being pouched forward, the so-called

“pigeon-breast” or “kangaroo pouch.” The bosomy effect was

combined with a tight waistline that forced the hips slightly back,

highlighting the rear end. This combination created the Gibson

“s-curve.” No statistics are available on increases in back trouble

among women during this period, but the exaggerated s- curve had to

cause back problems. But then this was not the

first time in history that human comfort and spinal health were

sacrificed on the altar of fashion. This

vast assortment of clothing was worn to church and social gatherings,

oftentimes on hot days, and it became the primary instrument of feminine

Victorian repression.

This

vast assortment of clothing was worn to church and social gatherings,

oftentimes on hot days, and it became the primary instrument of feminine

Victorian repression.  Young and beautiful Amelia Bloomer was quick to see the value of

this garment, and within days had made one for herself. She then

tried to popularize the fashion through her newsletter, The Lily. But

people in her hometown of Seneca Falls, and elsewhere as well, did not at all share her enthusiasm. They

taunted her and threw rocks and eggs at her and her friends every time

they came into town. After all, it may be somewhat tolerable to wear such

atrocious and sinful clothing in the privacy of one’s own home, far away from the public eye, but never

outdoors, and

absolutely never in the presence of men. Men wore pants. Women did not.

God did not intend women to wear pants. This was

clearly stated in the bible.

Young and beautiful Amelia Bloomer was quick to see the value of

this garment, and within days had made one for herself. She then

tried to popularize the fashion through her newsletter, The Lily. But

people in her hometown of Seneca Falls, and elsewhere as well, did not at all share her enthusiasm. They

taunted her and threw rocks and eggs at her and her friends every time

they came into town. After all, it may be somewhat tolerable to wear such

atrocious and sinful clothing in the privacy of one’s own home, far away from the public eye, but never

outdoors, and

absolutely never in the presence of men. Men wore pants. Women did not.

God did not intend women to wear pants. This was

clearly stated in the bible.

Soon

after the time of Daisy Bell's publication, bicycle sales were going

nowhere but up. With the rubber balloon tire, and all the other

ingenious mechanical improvements, such as a smaller spindle size and a

better chain drive, the bike of the middle 1890’s was fit for anybody

to ride even the ladies. The “safety” or “wheel”, as it was

then called, was so popular in both

Soon

after the time of Daisy Bell's publication, bicycle sales were going

nowhere but up. With the rubber balloon tire, and all the other

ingenious mechanical improvements, such as a smaller spindle size and a

better chain drive, the bike of the middle 1890’s was fit for anybody

to ride even the ladies. The “safety” or “wheel”, as it was

then called, was so popular in both  Bicycles

may certainly have played a roll in the cultural change that was

occurring over this same period, especially in the perception of a young

woman’s roll in society. Young ladies packed lunches, cast off their

petticoats (synonymous with bra-burning), donned the scandalous riding