Songs

Dominic

Vautier 1-11

After The

Ball

Charlie Harris got the idea to write After

The Ball during an incident he had witnessed in

Chicago

some years earlier while attending a formal ball. After the last dance, while Charlie and his friends were leaving,

he happened to overhear a quarrel between an attractive young lady and her

escort. The man finally

turned on his heel and went home in a huff, leaving her behind. She then burst into tears and left unescorted, which was quite an

embarrassment. The

scene left a lasting impression on Chuck Harris, who had a soft

spot in his heart for women. Later

that year Harris returned to

Milwaukee and completed perhaps the work of his lifetime.

Charlie Harris got the idea to write After

The Ball during an incident he had witnessed in

Chicago

some years earlier while attending a formal ball. After the last dance, while Charlie and his friends were leaving,

he happened to overhear a quarrel between an attractive young lady and her

escort. The man finally

turned on his heel and went home in a huff, leaving her behind. She then burst into tears and left unescorted, which was quite an

embarrassment. The

scene left a lasting impression on Chuck Harris, who had a soft

spot in his heart for women. Later

that year Harris returned to

Milwaukee and completed perhaps the work of his lifetime.

The

song is a story told by an old man to his little niece, the story of a woman that he had once taken to a ball when he was young.

He went to get her a glass of water and, upon returning, found

her in the arms of somebody else. Full

of anger, hostility, and disappointment, he left her then and there,

never to speak to her again, and she died of a broken heart. Years later the old man found out that the “other man” was

the young lady’s brother.

The

song is a story told by an old man to his little niece, the story of a woman that he had once taken to a ball when he was young.

He went to get her a glass of water and, upon returning, found

her in the arms of somebody else. Full

of anger, hostility, and disappointment, he left her then and there,

never to speak to her again, and she died of a broken heart. Years later the old man found out that the “other man” was

the young lady’s brother.

The gentle and lilting melody has

been a favorite from its first release. After the Ball’ is synonymous with the “Gay Nineties”, that

everlasting period of slow waltzes and broken hearts, canoe rides and

parasols. The song itself continued

to sell for the next 15 years. It

is said to have eventually sold about 6 million copies, and it has become a

part of our history.

After the

ball is over, after the break of morn,

After the dancers leaving, after the

stars are gone,

Many a heart is aching, if you could

read them all;

Many the hopes that have vanish’d

after the ball.[3]

My Gal Sal

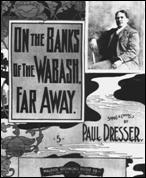

My Gal Sal was the swan song of Paul Dresser,

one

of the better known writers of Tin Pan Alley.

He had come to

New York

in 1886, and made his mark on the music industry by 1899 with his first big song, On the Banks on the

Wabash. By 1905, Dresser

was down on his luck, seriously overweight, poor, and in failing health.

Still, Paul Dresser took one last shot at fame and fortune. Just recently he had acquired the friendship of a young woman and

wrote a song about her. He

waived the manuscript of this recently written song in front of one of his

friends and said sadly, “Here is a song that should sell a million

copies, but I don’t have a dime to push it with”.[4]

He died the next day, probably of a heart attack, but Tin Pan

Alley forever maintained the legend that he died of a broken heart.

My Gal Sal was the swan song of Paul Dresser,

one

of the better known writers of Tin Pan Alley.

He had come to

New York

in 1886, and made his mark on the music industry by 1899 with his first big song, On the Banks on the

Wabash. By 1905, Dresser

was down on his luck, seriously overweight, poor, and in failing health.

Still, Paul Dresser took one last shot at fame and fortune. Just recently he had acquired the friendship of a young woman and

wrote a song about her. He

waived the manuscript of this recently written song in front of one of his

friends and said sadly, “Here is a song that should sell a million

copies, but I don’t have a dime to push it with”.[4]

He died the next day, probably of a heart attack, but Tin Pan

Alley forever maintained the legend that he died of a broken heart.

Your troubles, sorrows, and care,

She was always willing to share.

A mild sort of devil, but dead on the

level,

Was my gal Sal.[5]

Bird in a Gilded Cage

Harry Von Tilzer did something crazy,

hw wrote a parody. It turned out to be a poignant ballad about a girl who sold her

love to a rich old man. Ironically,

Von Tilzer wrote the song as a joke, a spoof of the tearjerker craze.

He meant for the song to be so stupid, so silly that people would

simply laugh. Harry could

not understand the popularity of such sentimental

drivel as After the Ball, and Little Lost Girl. He

had little sympathy for all the fabricated and overdone pathos that

flowed from so many of these songs. He felt that intelligent, urbane, metropolitan people, like those

living in New York, surely didn’t fall for the ridiculously sad material anymore.

So in

late 1899, Harry and his close friend, Art Lamb, were tossing around the

idea of writing a take-off on tearjerker songs, which would sound so

lugubrious that it would put all tearjerkers to shame. Lamb handed Von Tilzer some words and said, “I dare you to set

this to music.” Harry

casually stuck the words in his vest pocket and turned his attention to

other things.[6]

So in

late 1899, Harry and his close friend, Art Lamb, were tossing around the

idea of writing a take-off on tearjerker songs, which would sound so

lugubrious that it would put all tearjerkers to shame. Lamb handed Von Tilzer some words and said, “I dare you to set

this to music.” Harry

casually stuck the words in his vest pocket and turned his attention to

other things.[6]

A few days later, Harry joined some

friends in their usual Saturday night barhopping marathon, and ended up

in a house of unfavorable reputation. Since he was not particularly interested in joining in the

activities, he reached into his vest pocket and pulled out the words to

the “satire”. Feeling awkward at being board in the midst of merriment, and having

time on his hands with nothing else to do, he made the best of things, sat

down at the piano and composed a melody around the words.[7]

It wasn’t too much later that he had a song, and in his strong

baritone voice, began to sing. A

pall of silence fell over the house. Young girls, who were sitting close by, began to sob faintly.

Harry looked up and found himself surrounded by tearful young

ladies. He couldn’t

believe it.

She’s only a bird in a guilded

cage,

A beautiful sight to see.

You may think she is happy and free

from care,

She’s not though she seems to be.

It’s sad when you think of her

wasted life,

For youth cannot mate with age.

And her beauty was sold for an old

man’s gold,

She’s a bird in a guilded cage.[8]

Harry had composed the song of the

year, the “bird cage” song. What

began as a tearjerker put-on turned out to be the biggest hit of 1900. Bird in A Gilded Cage had the distinction of ringing in the new decade and the new century

as well.

Daisy Bell

In 1892, Harry Dacre, an Englishman

coming to America by steamer, was walking down the gangway carrying under his arm his most prized

possession, his bicycle. At

the foot of the ramp he was stopped by a customs inspector, who slapped

an import duty on his bike.

When the surprised immigrant

recounted the incident to fellow songwriter, William Jerome, his friend

replied, ”Well, just be glad it wasn’t a bicycle built for two.

Then they would have charged you double.”

The

words had a ring to them and Harry spent the next several weeks thinking

about what he could do with the phrase, “a bicycle built for two.”

He eventually wrote a catchy ballad about a young man who

couldn’t afford an expensive wedding, but who could afford a bike for

himself and his bride. Unable

to find a publisher, Harry gave the song to a friend who was going to England, and there it became a smash hit.

The new English songs popularity spread back to America

and in 1892 alone, Daisy Bell

sold over 2 million copies. 1892

was indeed a great year for music.

The

words had a ring to them and Harry spent the next several weeks thinking

about what he could do with the phrase, “a bicycle built for two.”

He eventually wrote a catchy ballad about a young man who

couldn’t afford an expensive wedding, but who could afford a bike for

himself and his bride. Unable

to find a publisher, Harry gave the song to a friend who was going to England, and there it became a smash hit.

The new English songs popularity spread back to America

and in 1892 alone, Daisy Bell

sold over 2 million copies. 1892

was indeed a great year for music.

Daisy,

Daisy, give me your answer true.

I’m half crazy, all for the love of

you.

It won’t be a stylish marriage.

I can’t afford a carriage,

But you’ll look sweet, upon the

seat

Of a bicycle built for two.[9]

The bicycle was

highly popular at this time, and like

the bicycle, Daisy Bell

continued to sell very well for the next 12 years, until

automobiles came along, but until then the destinies of both Daisy

Bell and the bicycle were connected.

The Band Played On

John Palmer was a out-of-work

actor when he wrote The Band

Played On. The title

phrase occurred to him when he was living with his sister in Manhattan.

He was shaving when she

called him downstairs to breakfast. “Hurry

up John, I’ve got your breakfast on the table!” she said. John hardly heard her; he was

standing by the window watching an itinerant German band play across the

street. “John, you didn’t hear a word I

said. Are you coming down,

or not?” She asked again.

John

replied “I’ll be down in

a second. I want to hear the

band play on.”[10]

When he finally did come downstairs,

his sister somewhat sarcastically said “And all this time since I

first called you, the band played on.”

At

this point John realized that the words could become a great title for a

song. The next day he wrote

the story of a friend of his, Matt Casey, who had an intense

relationship with a strawberry blonde. According to the song, she eventually became Mrs. Casey.

Palmer worked out a melody and tried to sell the song to Tin Pan

Alley with no takers. Finally an

ambitious young comedian actor from the Bowery named Charlie Ward made

some changes to the song and, by his own efforts, got it published.

At

this point John realized that the words could become a great title for a

song. The next day he wrote

the story of a friend of his, Matt Casey, who had an intense

relationship with a strawberry blonde. According to the song, she eventually became Mrs. Casey.

Palmer worked out a melody and tried to sell the song to Tin Pan

Alley with no takers. Finally an

ambitious young comedian actor from the Bowery named Charlie Ward made

some changes to the song and, by his own efforts, got it published.

Casey

would waltz with a strawberry blonde

And the band played on.

He’d glide ‘cross the floor

With the girl he adored,

And the band played on.

But his brain was so loaded

It nearly exploded.

The poor girl would shake with alarm.

He’d ne’er leave the girl

With the strawberry curls

And the band played on.[11]

Critics condemned this song. They said that it had no artistic value and that all of its

technical aspects were flawed. The

public apparently felt that it was the critics’ judgment that was

flawed. Consumers of popular

music loved the song and bought over a million copies of it.

The Curse

Paul Dresser carried a lot of weight,

emotionally as well as physically, and he put all of his 300 pounds into

his vaudeville stage act. To

describe his performance as impressive is an understatement. He was a man of extremes, sometimes very happy, sometimes very

unhappy, most of the time unhappy. This

was obvious in his music as well as in the affairs of his heart.

His marriage some time earlier to May

Howard was certainly no exception, for after a whirlwind honeymoon, they

separated, going their individual ways in pursuit of their own acting careers, and May continued to seek the kinds of worldly

pleasures and companionship she had been accustomed to before

they got married.

Paul Dresser had his dark

side, for while separated he wrote a song, intended to be sung to his

errant wife. For that

reason, at every one of his performances, he reserved a box in the hope

that some day she would do him the courtesy of attending one of his

shows. Finally, after

continued invitations, she did come. Paul Dresser, with his overpowering stage presence and in his

rich baritone voice, sang The Curse. This was the

first and only time the song was performed, because the music was

destroyed immediately after this performance. It is somewhat frightening to describe what happened.

We do know that women began screaming and fainting and crying. After the first chorus, many covered their ears, and many

more left the theater. May

Howard sat motionless throughout the song. She was never able to perform on stage again.

She had been completely and thoroughly undone by the episode. Paul

Dresser had visited his intense unhappiness upon his wife, whether or

not she deserved it.

My Gal is a High Born lady

The

song My Gal is a High Born Lady had everything needed to make it a ragtime hit;

great melody, good lyrics, and something altogether unique--ragtime

syncopation. It is

significant not only because it was the first true popular ragtime song,

but because it influenced many songs that came after it. The unusual dance step that it produced was very much like a fox

trot. However, its

slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm was not to get an appropriate name for

another 17 years, when Harry Fox introduced his fox trot dance

step. The ragtime trend that

My Gal started was to continue

for the next 20 years. Soon

after it came even bigger hits like Hello,

My Baby and Bill Bailey.

The

song My Gal is a High Born Lady had everything needed to make it a ragtime hit;

great melody, good lyrics, and something altogether unique--ragtime

syncopation. It is

significant not only because it was the first true popular ragtime song,

but because it influenced many songs that came after it. The unusual dance step that it produced was very much like a fox

trot. However, its

slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm was not to get an appropriate name for

another 17 years, when Harry Fox introduced his fox trot dance

step. The ragtime trend that

My Gal started was to continue

for the next 20 years. Soon

after it came even bigger hits like Hello,

My Baby and Bill Bailey.

Barney Fagan got the inspiration for

this song from, as he says, a broken bicycle pedal. He was riding home on his bike, dividing his attention between

the song he was thinking about and the worries he had about finding

enough money to buy his wife a birthday present.

Fagan was immediately struck by the unusual floppidy-flop rhythm

that the loose bike pedal created. Barney

suddenly realized that he could make the music he was working on fit

into this crazy “ragged” floppidy-flop rhythm, so he stopped, sat down by the side of the road, and composed

several measures. When Barney got

home he finished the first popular ragtime song, sold the piece for

$100, and bought his wife a birthday present.

Sidewalks

of

New York

Charles Lawlor wrote the music and

James Blake wrote the words to Sidewalks

of New York in 1894. More

than a century later, it is alive and well as the anthem of

New York City. The collaboration between

Lawlor and Blake began when Lawlor was looking for a new derby in a hat

shop where Blake worked. Lawlor,

a song-and-dance man in vaudeville, was humming a tune he had just made

up out of the blue. Blake liked it and asked

if he could try writing words to it[12].

For the rest of the day, between customers, Blake wrote. The words came easily because they were all about things he knew.

Charles Lawlor wrote the music and

James Blake wrote the words to Sidewalks

of New York in 1894. More

than a century later, it is alive and well as the anthem of

New York City. The collaboration between

Lawlor and Blake began when Lawlor was looking for a new derby in a hat

shop where Blake worked. Lawlor,

a song-and-dance man in vaudeville, was humming a tune he had just made

up out of the blue. Blake liked it and asked

if he could try writing words to it[12].

For the rest of the day, between customers, Blake wrote. The words came easily because they were all about things he knew.

Down in front of Casey’s old brown

wooden stoop,

On a summer’s evening we formed a

merry group.

Boys and girls together, we would

sing and waltz

While the Ginnie play the organ on

the sidewalks of New York.

Chorus:

East-side,

west-side, all around the town

The tots sing Ring-a-Rosie, London Bridge is falling down,

Boys and girls together, me and Mamie

O’Rourke,

Trip the light fantastic on the

sidewalks of New York.

That’s where Johnny Casey and

little Jimmy Crowe,

With Jakey Kruse, the baker, who

always had the dough,

Pretty Nellie Shannon, with a dude as

light as cork,

First picked up the waltz step on the

sidewalks of New York.[13]

The verses Blake wrote memorialized

his own growing up in New York. The house next door had a

brown stoop and belonged to a man named Higgins (Casey in the song

because it sounded better). They

bought their bread from old Jakey Kruse who owned a bakery down the

street. Jimmy was taught the

slow waltz by a neighbor girl named Mamie O’Rourke. His best friends were Johnny Higgins and Jimmy Crowe.

There was a beautiful young girl down the street named Nellie

Shannon, and she was dating a “dude” who dressed in flashy clothes.

Sidewalks

sold many copies and became extremely popular in the city. Governor Al Smith renamed it

East

Side, West Side and used it as his theme when he ran for president in 1928.

Wait Till the Sun Shines, Nellie

Harry Von Tilzer said this song was

his greatest work.[14]

He was the most respected and productive songwriter of the

period, the man whose works sold more copies of sheet music than any

other songwriter. This song quickly

sold well over a million copies in 1905.

Harry

had an amazing ability to observe people and use everyday situations as inspiration for

his songs. He

could see melody right in front of his eyes, and one simple incident

often would set him going. Sometimes

the melody came first, but usually he needed just the right words or the

right image.

Harry

had an amazing ability to observe people and use everyday situations as inspiration for

his songs. He

could see melody right in front of his eyes, and one simple incident

often would set him going. Sometimes

the melody came first, but usually he needed just the right words or the

right image.

In this case he was going home one afternoon

when he got caught in a big rainstorm. The

only shelter available was a nearby doorway where people were already

huddled to get away from the rain. As

Harry ducked into the doorway, he noticed a young man and

his girl friend, who was softly sobbing. The sudden rainstorm had ended their plans for a fun day at Coney Island,

and the man whispered to

his sweetheart, “Wait till the sun shines, Nellie.”

This single phrase and this image set

bells ringing in Harry’s head. He

raced back to his apartment, frantically worked out a melody to fit the

“Nellie” song, and asked his longtime friend and confidant, Andy

Sterling to help do the words. With

Nellie, Von Tilzer had completed his finest work.

Wait till the sun shines, Nellie,

When the clouds go drifting by,

We’ll be so happy, Nellie,

Don’t you cry.

Down lovers’ lane we’ll wonder,

Sweethearts you and I,

Wait till the sun shines, Nellie,

Bye and bye.[15]

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now

Harold Orlob and William Hough were

hard at work in 1909 on a Broadway play. Collaborating on a play is an association that often lasts a long

time, perhaps a year or more. Songwriters,

on the other hand, often work together no more than a few days.

This

is what happened when the two men wrote

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now. They were at a party and overheard some of the disappointed male

guests grumbling that a very popular young lady had not

shown up. One of the

impatient young men whispered under his breath, “I wonder who’s

kissing her now?” The

phrase and the situation inspired the two songwriters, who put this song

together over the next few weeks. They

included it in the musical play that they had been working on, The

Prince for Tonight. The

song was a giant success and is still done today, but the play flopped.

This

is what happened when the two men wrote

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now. They were at a party and overheard some of the disappointed male

guests grumbling that a very popular young lady had not

shown up. One of the

impatient young men whispered under his breath, “I wonder who’s

kissing her now?” The

phrase and the situation inspired the two songwriters, who put this song

together over the next few weeks. They

included it in the musical play that they had been working on, The

Prince for Tonight. The

song was a giant success and is still done today, but the play flopped.

I wonder who’s kissing her now.

I wonder who’s teaching her how.

I wonder who’s looking into her

eyes,

Breathing sighs, telling lies.

Sweet Adeline

Henry Armstrong and Richard Gerard

wrote the song Sweet Adeline in

1903 but they couldn’t get anybody to publish it. At first, they called the song Sweet

Rosalie. Unfortunately a lot of other Rosalie type songs were on the market, but they were still

undeterred. Nevertheless Sweet Rosalie

laid around for seven years gathering dust. Gerard was just about ready to give up when he learned that his

friend, Fred Rycroft, needed a good quartet song for his new barbershop

quartet, The

Quaker City Four. When

Gerard changed the name of the song to Sweet

Adeline, the chemistry of the change propelled the song into immortality.

Henry Armstrong and Richard Gerard

wrote the song Sweet Adeline in

1903 but they couldn’t get anybody to publish it. At first, they called the song Sweet

Rosalie. Unfortunately a lot of other Rosalie type songs were on the market, but they were still

undeterred. Nevertheless Sweet Rosalie

laid around for seven years gathering dust. Gerard was just about ready to give up when he learned that his

friend, Fred Rycroft, needed a good quartet song for his new barbershop

quartet, The

Quaker City Four. When

Gerard changed the name of the song to Sweet

Adeline, the chemistry of the change propelled the song into immortality.

Sweet Adeline,

My Adeline,

At night sweet heart,

For you I pine.

In all my

dreams,

In all my

dreams,

Your fair

face beams,

You’re the

flower of my heart,

Sweet

Adeline[18]

The song completely went off the charts.

From that day forward we have been blessed with the flowing

strains of the premier barbershop song of all time.

In

Boston, John J. Fitzgerald ran for Mayor using Adeline as his theme song.

Soon,

whenever he appeared at rallies or gatherings, everyone spontaneously

burst into close harmony. This

practice spread to the inebriated, and the citizens of Boston

were treated to a constant spectacle of groups of drunken singers

un-harmoniously attempting to perform this song at all hours of the day

and night. Things got so bad that Boston

officials seriously considered passing an ordinance that would outlaw

the singing of Sweet Adeline

within the city limits.[19]

Sweet Adeline came

close to being banned in

Boston.

In

Boston, John J. Fitzgerald ran for Mayor using Adeline as his theme song.

Soon,

whenever he appeared at rallies or gatherings, everyone spontaneously

burst into close harmony. This

practice spread to the inebriated, and the citizens of Boston

were treated to a constant spectacle of groups of drunken singers

un-harmoniously attempting to perform this song at all hours of the day

and night. Things got so bad that Boston

officials seriously considered passing an ordinance that would outlaw

the singing of Sweet Adeline

within the city limits.[19]

Sweet Adeline came

close to being banned in

Boston.

Casey Jones

When Casey Jones appeared in

print, Lawrence Seibert and Eddie Newton were credited with writing of

both words and music, but these two men were probably not the original authors, at least not

totally. Seibert and Newton

first heard the melody when some railroad workers were humming it and

decided it could be made into a decent song.

Railroad crews were accustomed to applying the

same music to various railroad catastrophes, using this tune and making

up different words to go with each new catastrophe. In this case they were singing about a certain railroad engineer Casey

Jones, who was involved in a tragic train wreck some years earlier.

It was on the night of Sunday, April

29, 1900, engineer John Luther Jones drove the fast cannonball express

out of Memphis. Simian Taylor Webb was the

fireman on board. The

regular engineer was sick and Casey and Sim Webb were called up as substitutes.

They were already eight hours late so you might say they were

both in a big hurry, highballing it, as the yardbirds[20]

say. When engine number 382

came around a bend with Casey at the throttle, the two found themselves

looking at the back of a freight car that was standing still on the

track directly in front of them. Casey

told Sim Webb to jump, and moments later, with Jones still at the

throttle trying to stop the speeding locomotive, the fast

cannonball express slammed into the freight train. Jones was killed instantly.

Webb

lived to tell the story[21]

It was on the night of Sunday, April

29, 1900, engineer John Luther Jones drove the fast cannonball express

out of Memphis. Simian Taylor Webb was the

fireman on board. The

regular engineer was sick and Casey and Sim Webb were called up as substitutes.

They were already eight hours late so you might say they were

both in a big hurry, highballing it, as the yardbirds[20]

say. When engine number 382

came around a bend with Casey at the throttle, the two found themselves

looking at the back of a freight car that was standing still on the

track directly in front of them. Casey

told Sim Webb to jump, and moments later, with Jones still at the

throttle trying to stop the speeding locomotive, the fast

cannonball express slammed into the freight train. Jones was killed instantly.

Webb

lived to tell the story[21]

Seibert write four verses for the

song, using the same melody he had picked up from the railroad workers, while

Newton arranged words around the melody.[22]

At first they had difficulty getting any publisher to look at the

song, but eventually it became a big seller, and highballing Casey was forever after an American legend.

On the banks of the

Wabash

On the banks of the Wabash became Paul Dresser’s big success

story. He wrote it after a

conversation with his brother, Theodore Dreiser[23],

who himself was later to become noted as a journalist and writer. Paul was feeling frustrated by the elusiveness of first-rate

success in the songwriting business. Theodore suggested that he write about something that he knew,

something about home, something that he was familiar with. “Why not write about the good old Wabash

and those fine sycamores growing along its banks?”[24]

Said Ted.

On the banks of the Wabash became Paul Dresser’s big success

story. He wrote it after a

conversation with his brother, Theodore Dreiser[23],

who himself was later to become noted as a journalist and writer. Paul was feeling frustrated by the elusiveness of first-rate

success in the songwriting business. Theodore suggested that he write about something that he knew,

something about home, something that he was familiar with. “Why not write about the good old Wabash

and those fine sycamores growing along its banks?”[24]

Said Ted.

Paul was inspired by his brother’s

words and went into his customary feverish activity, worked all night and

came up with a winner. On

the Banks of the Wabash was Paul Dresser’s masterpiece, sold well

over a million copies, and became understandably popular in Indiana, so much so that it soon was voted Indiana’s theme song.

This

experience gave Dresser renewed inspiration and propelled his faltering career into

serious songwriting. Although

he would never write another really successful song until just before he

died, this single song became the trademark of his life, and Indiana’s trademark as well.

My Old New Hampshire Home

This

song has not stood the test of time, as is the case with other songs in this section.

It was unbelievably popular in 1898, selling two million copies and

launching the Sterling-Von Tilzer team into stardom.

This

song has not stood the test of time, as is the case with other songs in this section.

It was unbelievably popular in 1898, selling two million copies and

launching the Sterling-Von Tilzer team into stardom.

Harry Von Tilzer and Andy Sterling

had rented an apartment together. They

were about two weeks behind on the rent, so one night they silently crept up to their third-floor apartment,

afraid to turn on the light for fear the manager would catch them and

throw them out. Andy placed

a sheet of paper against the windowpane (some say this piece of paper

was the rent notice) and, using the street lamp for light, wrote the

words to a song which commemorated Dewey’s victory at Manila

during the Spanish American war. Harry

put the words to music. They

were able to sell the song to a publisher, William Dunn for $5, and

later received an additional $10 after Dunn’s daughter told her publisher father that she liked

it very much. Dunn made considerable profit on the venture and Andy and Harry

were able to pay the rent.[25]

I’m Afraid to Come Home in the Dark

1905 and 1906 were good years for the

dynamic team of Harry Williams and Egburt Van Alstyne. They were able to put together several songs during this period,

songs such as In the Shade of the

Old Apple Tree, Cheyenne, Won’t You Come Over to My House, Why Don’t You Try, and

I’m Afraid to Come Home in the Dark. The last song was not the biggest hit, but it did

turn out to be a big hit in

New York City. In fact there were few places in town where the sonorous sounds of this

soft waltz were not heard.

O.

Henry, the mystery writer, loved this song. His real name was William Sydney Porter, and he began writing

short stories when he was in prison serving a two-year term for

embezzlement. He claimed

that he was framed, but then there was a mystery to that story. After Porter got out of prison he went to New York

to continue his career in writing short stories. In the few years left to him before his death he became a famous

writer, and an extremely familiar figure of his day on West 26th Street, Manhattan.

O.

Henry, the mystery writer, loved this song. His real name was William Sydney Porter, and he began writing

short stories when he was in prison serving a two-year term for

embezzlement. He claimed

that he was framed, but then there was a mystery to that story. After Porter got out of prison he went to New York

to continue his career in writing short stories. In the few years left to him before his death he became a famous

writer, and an extremely familiar figure of his day on West 26th Street, Manhattan.

By 1910 the short story writer was at

death’s door. He lay in deep coma in his darkened room at the Caledonia Hotel.

One afternoon he suddenly awoke from his coma at the sound of a

hurdy-gurdy[26]

outside his window playing his favorite melody, I’m Afraid to Come Home in the Dark. The surprised nurse rushed to Porter’s bedside to hear his

dying words, “Pull up the curtain, I’m afraid to come home in the

dark”.[27]

Nobody could figure out exactly what he meant. O. Henry ended his life as he had lived it, with one more

mystery.

I’d

Leave My Happy Home For You

In 1899 Harry Von Tilzer was still

struggling to make a name for himself.

Among his many skills, he was above all an accomplished piano player and was accompanying a play

in Hartford

Connecticut. A girl waited for him at

the stage door after one of the practices. She

told Harry she wanted to go to New York with him and become famous too.

Harry

said something offhand like “Well pack your bags and come along”.

In 1899 Harry Von Tilzer was still

struggling to make a name for himself.

Among his many skills, he was above all an accomplished piano player and was accompanying a play

in Hartford

Connecticut. A girl waited for him at

the stage door after one of the practices. She

told Harry she wanted to go to New York with him and become famous too.

Harry

said something offhand like “Well pack your bags and come along”.

A few days later, when the company

was about to leave, there she was, bags all packed and ready to go.

Harry gently tried to talk the girl out of coming to New York with him.

She took him to a

window, and pointed to her home, a magnificent house on the nearby hill.

“Oh Harry, I’d leave my happy home for you.”[28]

She said.0

I'm not sure how he got out of this

jam, but Harry wasn’t really ready to enter

into a full-time relationship with a rich, stage-struck girl. Her

words did made a kind of sense to him. He

immediately banged out a sketchy melody and asked a friend of his, Will

Heelan, to write lyrics for it using the phrase “I’d leave my

happy home for you”. Harry

got the song published and Harry’s friend, Blanche Ring, the Broadway

singer, popularized it. The

song became a million seller.[29]

When you were Sweet Sixteen

Jim Thornton was a successful

stand-up comedian. He was

also John L. Sullivan’s

favorite drinking buddy and piano player. This led to a life of serious bar hopping and even more serious

drinking. His wife Bonnie,

always one to worry about his health, once pouted. “Don’t you love me anymore, Jim?”

Never at a loss for words, Big Jim

quickly responded, “Why I love you like I did when you were sweet

sixteen.”

Never at a loss for words, Big Jim

quickly responded, “Why I love you like I did when you were sweet

sixteen.”

From this reply Jim was inspired to

work on a song which he completed in about two days of frantic

work. In the trouble-making

style that was characteristic of him, Thornton

sold the song for practically nothing to two different publishing houses

at the same time. Perhaps he

did it to make things interesting. The song sold millions and the two publishers, John W. Witmark

& Co., and Joseph W. Stern & Co. took the issue to court and

fought over copyright for the next 50 years. The copyright finally expired in 1944.

Jim had certainly made things interesting.

I love you as I never loved before,

Since first I met you on the village

green.

Come to me or my dream of love is

o’er.

I love you as I loved you

When you were sweet,

When you were sweet sixteen.[31]

Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown

Harry Von Tilzer was returning to

New York

after a visit to

Miami. While he was standing on

the wooden platform waiting for a train, he overheard a loud

conversation. “What you gonna’ do about the

rent? What you gonna’ say

to the landlord when he comes ‘round. You ain’t got no sense and you won’t have any on Judgment

Day!”

On his long trip back to New York

Harry turned the words over in his mind. When he got back he told his close friend Andy Sterling about the

incident. Together they

wrote this catchy ragtime song.[16]

Rufus Rastus Johnson Brown,

What you goin’ to do when the rent

comes ‘round?

What you goin’ to say, how you goin’

to pay

You’ll never have a bit of sense

till Judgment day.[17]

When I Lost You

This was the only sad song Irving

Berlin ever wrote, and it was completely based on his own experience.

In 1911, when the very successful songwriter was signing copies

of new music at his publishing house, two young women got

into a fight over a copy with his signature on it. Berlin

remarked later ”I used to dream of people fighting for the right to

sing my stuff, but this was the first time I saw that dream come

true”.[32]

He settled the argument this way. He gave the sheet music to one of the women and took the other

one out on a date. Her name

was Dorothy Goetz, the sister of Ray Goetz, a theatrical producer.

Dorothy Goetz was a petite brunette,

and within weeks the two were hopelessly in love and six months later

they were married. The

newlyweds escaped the cold weather of New York

City and went to Cuba

for their honeymoon, but an outbreak of typhoid fever in Havana

caused them to cut their vacation short. After their return, Dorothy became ill and she died of typhoid

fever five months later.

The tragically brief marriage left

this 23-year-old man devastated. He could not rid himself of despair and guilt feelings that

somehow he was responsible for his wife’s death. He had lost everything: his homeland, his father, his singing

career, and now his young wife. The

only thing left to him was his amazing songwriting ability.

To pay homage to his lost love, Berlin

did what he was best at, and wrote a song. When I Lost You was unusual, for this majestic waltz, done in slow

three-quarter time, hinted at a funeral dirge; its use of soft

diminished seventh’s almost gave one hope. The public proved that Berlin’s belief, that sad music doesn’t sell was wrong, when they

purchased well over a million copies.

My Melancholy baby

My

Melancholy baby was written in 1912. It is remarkable in several ways.

The authors, Earnest Burnett and George Norton, did little else

in the way of music, although Norton later composed the words for Memphis

Blues. The song had an

unusual title. It sputtered

out in 1912 and moldered away for almost 30 years, until Bing Crosby

dusted it off and made it a hit in 1939. The song was perfectly suited for the 1940’s era, and became

the first torch song ever written.[33]

It was simply written 30 years too early.[34]

Sweet Rosie O’Grady

Maude Nugent was a singer and dancer

in New York City

who in 1895 married Broadway songwriter Billy Jerome. She decided to try her hand at songwriting, and composed a soft

ballad called Sweet Rosie

O’Grady. Shy by

nature, she told no one about it for several weeks, even her songwriter

husband. When Maude finally

showed him what she had written, he was impressed and advised her to try

using it onstage. She

performed her song and brought the house down. Nugent became the first woman to write a modern American hit.[35]

Hot Time in the

Old

Town

Tonight

There is not much uncertainty about

who wrote Hot Time in

the Old Town Tonight but there is some question about where they got

the song. Ted Metz

presumably came up with the melody and some of the words, but the tune

was known to have been a well-established favorite at Babe Connors’

St. Louis

brothel well before Ted Metz ever heard of it.

Ted Metz had been to Babe’s and was

at least subconsciously familiar with the melody when the minstrel show

he was with stopped at a railroad junction near Old Town,

Louisiana. Some kids were playing

nearby and had built a huge bonfire, which spread to some nearby

railroad ties. Members of

the minstrel show piled out of the train and rushed to help local Old

Town

residents control the fire. In

the midst of all this pandemonium, one of the performers remarked glibly,

“They’ll be a hot time in the Old

Town

tonight!”

This phrase formed the core of a set

of lyrics that Metz

set to music, using the snappy melody he had remembered from Babe

Connors’ brothel. Joe

Hayden, a member of the minstrel group, helped him with the words.

From 1896 on, almost every minstrel show began its program with Hot Time. Two years

later, Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders charged up San Juan Hill

to this song. Hot Time was then adopted by American soldiers as the unofficial

Spanish American War song.

AFTER THE

WAR

“Welcome

home! Are you one of the heroic 71st?”

“No, I ain’t no hero. I’m

a regular.”

Charles

Dana Gibson, 1898.

Here are some other links in this

article:

Origins

of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People

Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

How

Dancing Helped Music

Women

and Early Music

Some

Early Songwriters

The

Influence of the Piano

Recorded

Music

Sheet Music

Chronicles

1892-1900

Chronicles

1901-1915

Million

Sellers

[1]

Andrew Sterling and Kerry Mills, Meet

Me in St. Louis, Louis, 1904.

[2]

Maxwell F. Marcuse, Tin

Pan Alley In Gaslight (New York: Century House, 1959), 140.

[3]

Charles K. Harris, After the

Ball, 1892.

[4]

Marcuse, 128.

[5]

Paul Dresser, My Gal Sal,

1905.

[6]

Some historians suggest that Harry objected to the lyrics: the young

girl had to be married to the old man and not just his paramour, and

Von Tilzer insisted that Lamb rewrite the lyrics. Douglas Gilbert, (Lost

Chords, Cooper Square Publishers, 1970, p.318) states that it

was Bernstein, the publisher, who made Lamb change the lyrics and

not Von Tilzer at all. Gilbert’s

version may be more credible because two years later the same team

of Lamb & Von Tilzer wrote a follow-up song about a whorehouse

called Mansion of

Aching Hearts.

[7]

Sigmund Spaeth, Read ‘em and

Weep (New York: Arco Publishing Company, 1945), 205.

[8]

Andrew Lamb & Harry Von Tilzer,

Bird in a Guilded Cage, 1900.

[9]

Harry Dacre, Daisy Bell, 1892.

[10]

Marcuse, 174.

[11]

Palmer & Ward, Band Played

On, 1895.

[12]

Gilbert, 257.

[13]

Blake & Lawlor, Sidewalks

of New York, 1894.

[14]

Marcuse, 329

[15]

Andrew Sterling & Harry Von Tilzer, Wait

Till The Sun Shines, Nellie, 1905.

[16]

Marcuse, 328

[17]

Andrew Sterling & Harry Von Tilzer, What

You Going To Do When the Rent Comes Round, 1905.

[18]

Girard & Armstrong, Sweet

Adeline, 1903.

[19]

Marcuse, 305

[20]

People who work in the train yards.

[21]

The New York Times, July,

1957.

[22]

Marcuse, 411.

[23]

Paul had changed his name to Dresser when he went into song writing.

It sounded more American.

[24]

Marcuse, 229.

[25]

Burton

, 133.

[26]

A type of hand cranked organ used by street vendors.

[27]

Burton

, 129.

[28]

Spaeth, 209.

[29]

Burton

, 134.

[30]

John L. Sullivan (1858-1918), known as “The Great John L,” held

the world heavyweight boxing title for 10 years from 1882 until 1892

when he was knocked out by “Gentleman Jim” Corbett in 21 rounds.

[31]

Jim Thornton, When You Were

Sweet Sixteen, 1898.

[32]

Laurence B Bergreen, As

Thousands Cheer. (New

York: Viking, 1990), 81.

[33]

Allec Wilder, American Popular

Song, (New York, Oxford University Press, 1972), 17.

[34]

The term “torch song” didn’t come into use until about 1927.

It describes any slow ballad containing a theme of unrequited

or lost love. The

expression “to carry a torch for someone” means that love is not

reciprocated, and that the other party does not accept the torch of

love.

[35]

Maude Nugent’s authorship is disputed by some who feel that her

husband wrote the songs and had her take responsibility because the

arrangement proved to be more successful. None of this was ever proved.

Charlie Harris got the idea to write After

The Ball during an incident he had witnessed in

Chicago

some years earlier while attending a formal ball. After the last dance, while Charlie and his friends were leaving,

he happened to overhear a quarrel between an attractive young lady and her

escort. The man finally

turned on his heel and went home in a huff, leaving her behind. She then burst into tears and left unescorted, which was quite an

embarrassment. The

scene left a lasting impression on Chuck Harris, who had a soft

spot in his heart for women. Later

that year Harris returned to

Milwaukee and completed perhaps the work of his lifetime.

Charlie Harris got the idea to write After

The Ball during an incident he had witnessed in

Chicago

some years earlier while attending a formal ball. After the last dance, while Charlie and his friends were leaving,

he happened to overhear a quarrel between an attractive young lady and her

escort. The man finally

turned on his heel and went home in a huff, leaving her behind. She then burst into tears and left unescorted, which was quite an

embarrassment. The

scene left a lasting impression on Chuck Harris, who had a soft

spot in his heart for women. Later

that year Harris returned to

Milwaukee and completed perhaps the work of his lifetime. The

song is a story told by an old man to his little niece, the story of a woman that he had once taken to a ball when he was young.

He went to get her a glass of water and, upon returning, found

her in the arms of somebody else. Full

of anger, hostility, and disappointment, he left her then and there,

never to speak to her again, and she died of a broken heart. Years later the old man found out that the “other man” was

the young lady’s brother.

The

song is a story told by an old man to his little niece, the story of a woman that he had once taken to a ball when he was young.

He went to get her a glass of water and, upon returning, found

her in the arms of somebody else. Full

of anger, hostility, and disappointment, he left her then and there,

never to speak to her again, and she died of a broken heart. Years later the old man found out that the “other man” was

the young lady’s brother.

So in

late 1899, Harry and his close friend, Art Lamb, were tossing around the

idea of writing a take-off on tearjerker songs, which would sound so

lugubrious that it would put all tearjerkers to shame. Lamb handed Von Tilzer some words and said, “I dare you to set

this to music.” Harry

casually stuck the words in his vest pocket and turned his attention to

other things.

So in

late 1899, Harry and his close friend, Art Lamb, were tossing around the

idea of writing a take-off on tearjerker songs, which would sound so

lugubrious that it would put all tearjerkers to shame. Lamb handed Von Tilzer some words and said, “I dare you to set

this to music.” Harry

casually stuck the words in his vest pocket and turned his attention to

other things. The

words had a ring to them and Harry spent the next several weeks thinking

about what he could do with the phrase, “a bicycle built for two.”

He eventually wrote a catchy ballad about a young man who

couldn’t afford an expensive wedding, but who could afford a bike for

himself and his bride. Unable

to find a publisher, Harry gave the song to a friend who was going to England, and there it became a smash hit.

The new English songs popularity spread back to America

and in 1892 alone, Daisy Bell

sold over 2 million copies. 1892

was indeed a great year for music.

The

words had a ring to them and Harry spent the next several weeks thinking

about what he could do with the phrase, “a bicycle built for two.”

He eventually wrote a catchy ballad about a young man who

couldn’t afford an expensive wedding, but who could afford a bike for

himself and his bride. Unable

to find a publisher, Harry gave the song to a friend who was going to England, and there it became a smash hit.

The new English songs popularity spread back to America

and in 1892 alone, Daisy Bell

sold over 2 million copies. 1892

was indeed a great year for music. At

this point John realized that the words could become a great title for a

song. The next day he wrote

the story of a friend of his, Matt Casey, who had an intense

relationship with a strawberry blonde. According to the song, she eventually became Mrs. Casey.

Palmer worked out a melody and tried to sell the song to Tin Pan

Alley with no takers. Finally an

ambitious young comedian actor from the Bowery named Charlie Ward made

some changes to the song and, by his own efforts, got it published.

At

this point John realized that the words could become a great title for a

song. The next day he wrote

the story of a friend of his, Matt Casey, who had an intense

relationship with a strawberry blonde. According to the song, she eventually became Mrs. Casey.

Palmer worked out a melody and tried to sell the song to Tin Pan

Alley with no takers. Finally an

ambitious young comedian actor from the Bowery named Charlie Ward made

some changes to the song and, by his own efforts, got it published.

The

song My Gal is a High Born Lady had everything needed to make it a ragtime hit;

great melody, good lyrics, and something altogether unique--ragtime

syncopation. It is

significant not only because it was the first true popular ragtime song,

but because it influenced many songs that came after it. The unusual dance step that it produced was very much like a fox

trot. However, its

slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm was not to get an appropriate name for

another 17 years, when Harry Fox introduced his fox trot dance

step. The ragtime trend that

My Gal started was to continue

for the next 20 years. Soon

after it came even bigger hits like Hello,

My Baby and Bill Bailey.

The

song My Gal is a High Born Lady had everything needed to make it a ragtime hit;

great melody, good lyrics, and something altogether unique--ragtime

syncopation. It is

significant not only because it was the first true popular ragtime song,

but because it influenced many songs that came after it. The unusual dance step that it produced was very much like a fox

trot. However, its

slow-slow-quick-quick rhythm was not to get an appropriate name for

another 17 years, when Harry Fox introduced his fox trot dance

step. The ragtime trend that

My Gal started was to continue

for the next 20 years. Soon

after it came even bigger hits like Hello,

My Baby and Bill Bailey. Charles Lawlor wrote the music and

James Blake wrote the words to Sidewalks

of New York in 1894. More

than a century later, it is alive and well as the anthem of

Charles Lawlor wrote the music and

James Blake wrote the words to Sidewalks

of New York in 1894. More

than a century later, it is alive and well as the anthem of Harry

had an amazing ability to observe people and use everyday situations as inspiration for

his songs. He

could see melody right in front of his eyes, and one simple incident

often would set him going. Sometimes

the melody came first, but usually he needed just the right words or the

right image.

Harry

had an amazing ability to observe people and use everyday situations as inspiration for

his songs. He

could see melody right in front of his eyes, and one simple incident

often would set him going. Sometimes

the melody came first, but usually he needed just the right words or the

right image. This

is what happened when the two men wrote

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now. They were at a party and overheard some of the disappointed male

guests grumbling that a very popular young lady had not

shown up. One of the

impatient young men whispered under his breath, “I wonder who’s

kissing her now?” The

phrase and the situation inspired the two songwriters, who put this song

together over the next few weeks. They

included it in the musical play that they had been working on, The

Prince for Tonight. The

song was a giant success and is still done today, but the play flopped.

This

is what happened when the two men wrote

I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now. They were at a party and overheard some of the disappointed male

guests grumbling that a very popular young lady had not

shown up. One of the

impatient young men whispered under his breath, “I wonder who’s

kissing her now?” The

phrase and the situation inspired the two songwriters, who put this song

together over the next few weeks. They

included it in the musical play that they had been working on, The

Prince for Tonight. The

song was a giant success and is still done today, but the play flopped. Henry Armstrong and Richard Gerard

wrote the song Sweet Adeline in

1903 but they couldn’t get anybody to publish it. At first, they called the song Sweet

Rosalie. Unfortunately a lot of other Rosalie type songs were on the market, but they were still

undeterred. Nevertheless Sweet Rosalie

laid around for seven years gathering dust. Gerard was just about ready to give up when he learned that his

friend, Fred Rycroft, needed a good quartet song for his new barbershop

quartet, The

Quaker City Four. When

Gerard changed the name of the song to Sweet

Adeline, the chemistry of the change propelled the song into immortality.

Henry Armstrong and Richard Gerard

wrote the song Sweet Adeline in

1903 but they couldn’t get anybody to publish it. At first, they called the song Sweet

Rosalie. Unfortunately a lot of other Rosalie type songs were on the market, but they were still

undeterred. Nevertheless Sweet Rosalie

laid around for seven years gathering dust. Gerard was just about ready to give up when he learned that his

friend, Fred Rycroft, needed a good quartet song for his new barbershop

quartet, The

Quaker City Four. When

Gerard changed the name of the song to Sweet

Adeline, the chemistry of the change propelled the song into immortality.

In all my

dreams,

In all my

dreams, In

Boston, John J. Fitzgerald ran for Mayor using Adeline as his theme song.

Soon,

whenever he appeared at rallies or gatherings, everyone spontaneously

burst into close harmony. This

practice spread to the inebriated, and the citizens of Boston

were treated to a constant spectacle of groups of drunken singers

un-harmoniously attempting to perform this song at all hours of the day

and night. Things got so bad that Boston

officials seriously considered passing an ordinance that would outlaw

the singing of Sweet Adeline

within the city limits.

In

Boston, John J. Fitzgerald ran for Mayor using Adeline as his theme song.

Soon,

whenever he appeared at rallies or gatherings, everyone spontaneously

burst into close harmony. This

practice spread to the inebriated, and the citizens of Boston

were treated to a constant spectacle of groups of drunken singers

un-harmoniously attempting to perform this song at all hours of the day

and night. Things got so bad that Boston

officials seriously considered passing an ordinance that would outlaw

the singing of Sweet Adeline

within the city limits. It was on the night of Sunday, April

29, 1900, engineer John Luther Jones drove the fast cannonball express

out of Memphis. Simian Taylor Webb was the

fireman on board. The

regular engineer was sick and Casey and Sim Webb were called up as substitutes.

They were already eight hours late so you might say they were

both in a big hurry, highballing it, as the yardbirds

It was on the night of Sunday, April

29, 1900, engineer John Luther Jones drove the fast cannonball express

out of Memphis. Simian Taylor Webb was the

fireman on board. The

regular engineer was sick and Casey and Sim Webb were called up as substitutes.

They were already eight hours late so you might say they were

both in a big hurry, highballing it, as the yardbirds On the banks of the Wabash became Paul Dresser’s big success

story. He wrote it after a

conversation with his brother, Theodore Dreiser

On the banks of the Wabash became Paul Dresser’s big success

story. He wrote it after a

conversation with his brother, Theodore Dreiser This

song has not stood the test of time, as is the case with other songs in this section.

It was unbelievably popular in 1898, selling two million copies and

launching the Sterling-Von Tilzer team into stardom.

This

song has not stood the test of time, as is the case with other songs in this section.

It was unbelievably popular in 1898, selling two million copies and

launching the Sterling-Von Tilzer team into stardom. O.

Henry, the mystery writer, loved this song. His real name was William Sydney Porter, and he began writing

short stories when he was in prison serving a two-year term for

embezzlement. He claimed

that he was framed, but then there was a mystery to that story. After Porter got out of prison he went to New York

to continue his career in writing short stories. In the few years left to him before his death he became a famous

writer, and an extremely familiar figure of his day on West 26th Street, Manhattan.

O.

Henry, the mystery writer, loved this song. His real name was William Sydney Porter, and he began writing

short stories when he was in prison serving a two-year term for

embezzlement. He claimed

that he was framed, but then there was a mystery to that story. After Porter got out of prison he went to New York

to continue his career in writing short stories. In the few years left to him before his death he became a famous

writer, and an extremely familiar figure of his day on West 26th Street, Manhattan. In 1899 Harry Von Tilzer was still

struggling to make a name for himself.

Among his many skills, he was above all an accomplished piano player and was accompanying a play

in Hartford

Connecticut. A girl waited for him at

the stage door after one of the practices. She

told Harry she wanted to go to New York with him and become famous too.

Harry

said something offhand like “Well pack your bags and come along”.

In 1899 Harry Von Tilzer was still

struggling to make a name for himself.

Among his many skills, he was above all an accomplished piano player and was accompanying a play

in Hartford

Connecticut. A girl waited for him at

the stage door after one of the practices. She

told Harry she wanted to go to New York with him and become famous too.

Harry

said something offhand like “Well pack your bags and come along”. Never at a loss for words, Big Jim

quickly responded, “Why I love you like I did when you were sweet

sixteen.”

Never at a loss for words, Big Jim

quickly responded, “Why I love you like I did when you were sweet

sixteen.”