Dominic Vautier 8/7/2011

England

or Spain, it was always the same,

He’d be there at that

“piana”

On the cruiser Alabama,

Ev’ry mornin’, noon, and night

He would keep it up with all his might

Ev’ry time he’d start a playin’

All the boys would start a-swayin’. [1]

Why did early popular music depend on the piano so much? The answer lies in the basic union it had with the music industry, a condition that came about much by design. Popular music was sheet music, and sheet music was piano music. This basic relationship would not change until later, after 1915. The piano and popular music were irrevocably joined in a way we may not easily understand today. In today’s world there are many methods of musical reproduction, but in those times it was the piano, and in many areas, only the piano.

Our grandfathers and grandmothers made this instrument an indispensable part of their entertainment. That special attachment was passed on to us albeit indirectly through their wishes, intimations, aspirations, fantasies, and dreams. Most everything they did in the way of artistic expression was somehow connected to the piano, for it was oftentimes the center of their social lives.

World civilization spent several thousand years thinking about building piano-like instruments, but delayed the actual construction. After all, there was no written music, clefs, staffs, rests, notation, tempos, harmony, rhythm, or melodic phrasing. None of those things existed. Only wandering troubadours and rag-tag minstrels, accompanied by lutes and horns, and harps and liras plied the trade. Most of the music was monotone or duotone, repeated from memory, with no particular need for a way to record it. So who needed anything like a piano? The world wasn't ready.

Surprisingly, a keyboard instrument would not have involved any new inventions or technological breakthroughs. After all, a keyboard instrument is nothing more than a collection of strings, wood, hammers, levers, pulleys, fulcrums, sounding boards, and keys, all abundantly available technologies since antiquity. In the third century BC the Greeks did invent a water organ that had wooden sliders for keys. It used compressed air from a water-driven reservoir. When the slide was opened, air rushed from a tuned pipe producing a note. This was the first attempt ever to create a keyboard-like instrument. Unfortunately, since there was no written music or musical notation or anything else around to help people create and remember music, this wonderful and novel invention remained nothing more than a curiosity and soon became lost, like so many other great ideas whose time had not yet come.

The Romans probably would have had little trouble developing a keyboard instrument if they had wanted to, judging from their high skill in building intricate machines of war and ingenious aqueducts. But their interests lay in other areas like war and killing. The more artistic and educated Greeks were expected to furnish the niceties of life, like music, art, philosophy, and sculpture. Romans had more serious things to do. So for the better part of recorded history we had to make do with a single-string instrument called the monochord, essentially a guitar with one string, because one string was about as sophisticated as the musical environment needed to be.

By the 9th century musical harmony arrived on the scene, and by about the end of the 14th century, the Italians had finally invented a keyboard device with several octaves called the clavichord. It consisted of multiple keys attached to brass hammers that struck a corresponding string. The clavichord was not very loud and broke easily, but it was nonetheless, the first commercially successful keyboard instrument.

Soon came the next step in musical innovation, the harpsichord, which was a clavichord with some improvements. An important improvement was the replacement of the hammer action of the clavichord with a quill. Instead of hitting the string, the quill plucked the string, giving it a somewhat more pleasant sound. Early harpsichords were usually not expected to last through a concert, however, before a quill or a string broke, so artists were still very much at the mercy of their instruments.

Concert

harpsichords were huge, and there was no way to control volume, so it

produced sound at only one level, which was usually too loud. It had two smaller cousins, the virginal and the spinet, which

were not as loud. So still remaining

was the problem of volume control, since it would have been very

difficult for an artist to switch from a harpsichord to a virginal every

time he wanted to change volume. Sometimes

there were two performers playing, the soft passages being performed on

the spinet and the louder music on the harpsichord.

Concert

harpsichords were huge, and there was no way to control volume, so it

produced sound at only one level, which was usually too loud. It had two smaller cousins, the virginal and the spinet, which

were not as loud. So still remaining

was the problem of volume control, since it would have been very

difficult for an artist to switch from a harpsichord to a virginal every

time he wanted to change volume. Sometimes

there were two performers playing, the soft passages being performed on

the spinet and the louder music on the harpsichord.

In 1700, the pianoforte was finally invented. The word pianoforte (or fortepiano) stresses the idea of volume control (or “soft-loud”) because its inventor, Bartolomeo Cristofori wanted to emphasize that his wonderful instrument could play soft like the spinet, or loud like the harpsichord, depending on how hard the keys were pressed. The pianoforte was profoundly different from all other keyboard instruments of its day because it struck the strings, not with brass hammers like the clavichord, but with felt hammers but the strength of the hammer-blow depended on the amount of force exerted on the key. The pianoforte was accepted with little notice and less enthusiasm. Nobody immediately appreciated the value of being able to change volume.

Franz Liszt in action

Early

pianos were notoriously unreliable because they had a lot of moving

parts. The action, that is,

the mechanism controlling the hammer, was far more complicated than the

actions of the other simpler keyboard instruments (harpsichords,

virginals, and spinets). With

these new pianos, keys often got stuck, pedals jammed, and--most

frequently--strings would break. [2] The reason for string breakage was often because the wood frame

was unable to withstand the great pressure of stronger, heavier, and

tighter strings. Franz

Liszt, the most famous composer-performer of his time, was renown for

his forceful renditions. This

earned him the nickname “the great string buster” because he usually

went through three or four pianos during a typical performance.

Early

pianos were notoriously unreliable because they had a lot of moving

parts. The action, that is,

the mechanism controlling the hammer, was far more complicated than the

actions of the other simpler keyboard instruments (harpsichords,

virginals, and spinets). With

these new pianos, keys often got stuck, pedals jammed, and--most

frequently--strings would break. [2] The reason for string breakage was often because the wood frame

was unable to withstand the great pressure of stronger, heavier, and

tighter strings. Franz

Liszt, the most famous composer-performer of his time, was renown for

his forceful renditions. This

earned him the nickname “the great string buster” because he usually

went through three or four pianos during a typical performance.

The

majority of the early instruments were square pianos, so called because

they resembled boxes and the strings were laid out and ran horizontally.

In 1735 the first uprights appeared with their strings running

vertically. By 1855 constant

improvements to the upright had made it a far superior instrument, and

by 1880 square pianos were no longer being produced, although there were

still a lot of older square pianos around.

The

majority of the early instruments were square pianos, so called because

they resembled boxes and the strings were laid out and ran horizontally.

In 1735 the first uprights appeared with their strings running

vertically. By 1855 constant

improvements to the upright had made it a far superior instrument, and

by 1880 square pianos were no longer being produced, although there were

still a lot of older square pianos around.

In 1772 the first grand pianos were built. Grands were always the favorite among top musicians because of their superior sound and volume characteristics, but they were usually quite expensive, took up a lot of space, and were heavy and bulky. Grand pianos never constituted more than about 3 percent of all pianos.

1397-First reference to clavichord

1404-First clavichord

1425-First appearance of harpsichord

1460-First virginal

1490-Oldest surviving clavichord

1521-Oldest surviving harpsichord

1523-Oldest surviving spinet

1700-Cristofori invented the pianoforte

1735-First upright

1736-First spinet in America

1772-First grand

1773-First piano concert in New York

1789-First piano factory in America

1800-Floor-level strings for upright

1812-No more harpsichords made

1825-First iron frame square piano

1855-First overstring

1859-Overstring grand invented

1880-Last square piano made

1880-First player piano

1900-First Pianola

In the United States before 1850 there were a few pianos around. Most of them were square type pianos, where the frame consisted completely of wood. There were some grand pianos around for people who could afford them. All pianos were imported from Europe, especially the two great piano-making countries, Germany and England. Starting in 1850 the American piano industry began to break out of its inferiority complex, even though this country was still considered a cultural backwash, and piano manufacturing in the United States was quite inferior to the quality coming from Europe. From 1830 to 1850 many of the top German craftsmen and artists emigrated to America to flee political oppression then raging in their home country. These craftsmen immediately set about manufacturing violins, parlor organs, pianos, horns, and other musical instruments, for America was then a most encouraging environment for this type of energetic small business activity.

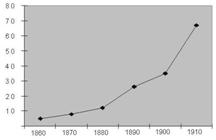

1900 presented a totally different picture. America did not just make the best pianos in the world; it made well over half of the world’s supply of pianos. [3] From the top-of-the-line Steinway grands from New York to the cheap but still relatively high-quality Kimball uprights out of Chicago, America had gained almost complete control of the world’s piano market in a mere 50 years. Few people realize, considering the pace of life and the small, down-home, local American markets, that the number of pianos being sold then represented a significant accomplishment in terms of market penetration, sales growth, price management, and manufacturing efficiency. In 1900, the piano industry employed 6 times as many people as it did in 1860. In 30 years’ time American business ingenuity’s triumph was complete. By creating in the minds of the emerging middle-class American public a genuine expectation that social value and true individual enrichment could be gotten by the purchase of one of these fine instruments, retailers were able to develop a huge market for pianos where none had existed before.

Just

so we can appreciate the rate of growth in this area from 1860 to 1910,

let’s set the piano industrial growth in 1899 equal to 100 percent.

By comparison, in 1860 it was only 16 percent and in 1910 it was

172 percent. Steinway,

Baldwin, Kimball, and all the other piano manufacturers were having a

well-deserved feeding frenzy in a market of their own making.

Just

so we can appreciate the rate of growth in this area from 1860 to 1910,

let’s set the piano industrial growth in 1899 equal to 100 percent.

By comparison, in 1860 it was only 16 percent and in 1910 it was

172 percent. Steinway,

Baldwin, Kimball, and all the other piano manufacturers were having a

well-deserved feeding frenzy in a market of their own making.

By 1880 piano imports became unimportant. Local piano production increased quickly, and the quality of the manufacturing was also without equal, becoming the envy even of Europe, for by 1900 both Germany and England finally had to admit that they had been outdone by the Americans.

Growth of American Piano manufacturing. [4]

|

Year |

Firms |

Labor |

Pianos |

Value |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1860 |

110 |

3,000 |

20,000 |

5,000,000 |

|

1870 |

156 |

4,000 |

24,000 |

8,000,000 |

|

1880 |

174 |

8,000 |

30,000 |

12,000,000 |

|

1890 |

236 |

12,000 |

72,000 |

26,000,000 |

|

1900 |

263 |

18,000 |

171,000 |

35,000,000 |

|

1910 |

294 |

25,000 |

374,000 |

67,000,000 |

A parlor organ, or harmonium, is also referred to as an American organ. It was a keyboard instrument that used air forced over reeds by bellows pumped by the player’s feet. It was light, transportable, and easily assembled. Some of these instruments could be folded to the size of a small trunk.

Many parlor organs were produced and sold toward the end of the 1800s, yet not much recognition is given to this instrument. The parlor organ was like a piano with training wheels. It was a stepping stone more serious investment, like a real piano. It was the poor man’s piano. It was a way to see if the purchase of such piano could be justified by clear demonstration of skill, aptitude, and dedication. Besides it was an easy way to learn and practice.

I suspect that much of earlier popular music was written so it could be performed equally well on the piano and the parlor organ. Musical notes were sustained and melodies tended to avoid staccato and syncopation, or anything that was difficult to do on the organ. As popular music evolved, as wages went up, and as pianos became more affordable, sales of parlor organs decreased. Sheet music also became more specifically piano oriented.

The use of parlor organs tended to precede that of the piano in the westward movement of populations. This shouldn’t be much of a surprise since they were lighter, smaller, and represented a far lower capital investment.

Comparison of sales of parlor organs and pianos in two different states [5]

|

Year |

New York Pianos |

Illinois Pianos |

Illinois Parlor organs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1880 |

6.6 |

0.04 |

0.6 |

|

1890 |

14.5 |

0.75 |

2.7 |

|

1900 |

14.4 |

6.9 |

1.2 |

|

1904 |

16.7 |

9.7 |

1.7 |

|

1909 |

23.8 |

14.7 |

0.9 |

So it seems that as civilization developed and moved westward, the use of parlor organs came first, and then they were gradually replaced by the more expensive and heavier piano. As people got richer they could afford the pianos, and as roads got better and safer, people were able to bring their heavier pianos along with them.

In larger stores, pianos, washing machines, and sewing machines were grouped together. They were sold by the same dealer or outlet because all these things had the same user, the housewife. These items were all bulky gadgets that women could use in the home, and they were all about the same price--expensive. For this reason, some manufacturers built both sewing machines and pianos in the same factory, even though the manufacturing techniques were different.[6] Maybe all these devices depended upon the digital dexterity that was characteristic and expected of the proper and God-fearing Victorian housewife, and the piano was often seen as a way to keep her busy, productive, and out of trouble. Besides, a substantial amount of advertising pressure could be brought to bear by linking sewing machines and pianos together. It appears to have worked.

Piano retailers used other Victorian social pressures to make sales. They suggested that a piano in the home developed a discipline of character, an order of mind, and a grace of spirit that motivated woman to remain steadfast in devotion to home, husband, and family. By asserting that the uplifting qualities of piano music tended to enrich an otherwise average household, the retailers were able to play upon the sensitivities of the public and create a substantial demand for their product.

Another area of exploitation was education. Manufacturers and retailers alike heavily advertised the use of musical instruments, primarily the piano, as a valuable tool to preserve order in school assemblies and school concerts. They fostered school plays, dances, and amateur hours. Nothing was spared in the relentless pursuit of sales. Retailers constantly extolled the many virtues of piano playing in the public schools as a sure way to develop self-control and discipline, promote order, and create a true capacity for artistic appreciation. [7]

1907 postcard titled "Try this on your Piano."

Then, as now, America was driven by fads. The enormous expansion in the sale of pianos that took place between 1890 and 1910 was unparalleled in our history. In fact from 1870 until 1890 the sale of pianos increased at a rate 1.6 times as fast as the increase in population. That rate grew to 5.6 times the population expansion between 1890 and 1900, and finally the highest rate increase was achieved from 1900 through 1910, when piano sales increased 6.2 times faster than the population, which as we see in Baby Boom was itself increasing dramatically. [8]

All of this tells us that a lot of pianos were being sold. A little arithmetic further illustrates that there were probably more than two million pianos, parlor organs, and other keyboard devices in use by 1900. That number would increase to about 5.5 million by 1910. Piano manufacturing reached its highest level of production that same year, when American plants were able to produce around 500,000 pianos.

Heinrich Steinwig made his first piano in 1836 in

Brunswick, Germany. He emigrated to

America

in 1848, along with his wife and five of his children, and changed his

name to Steinway. In 1853,

after years of planning, Steinway set up his own business and began

making pianos. By 1859 the

Steinways perfected a special method of overstringing. They incorporated a heavy cast iron frame to support bigger

strings. They relocated the

sounding-board bridge and dramatically increased string tension to

produce a much-improved sound. In

short, Steinway basically created the piano we have today. No other significant improvements have been made since that time

except for some hammer and damper movement refinements. [9]

The Steinways of New York became sole leaders of quality

pianos, and they remained so for many years.

Heinrich Steinwig made his first piano in 1836 in

Brunswick, Germany. He emigrated to

America

in 1848, along with his wife and five of his children, and changed his

name to Steinway. In 1853,

after years of planning, Steinway set up his own business and began

making pianos. By 1859 the

Steinways perfected a special method of overstringing. They incorporated a heavy cast iron frame to support bigger

strings. They relocated the

sounding-board bridge and dramatically increased string tension to

produce a much-improved sound. In

short, Steinway basically created the piano we have today. No other significant improvements have been made since that time

except for some hammer and damper movement refinements. [9]

The Steinways of New York became sole leaders of quality

pianos, and they remained so for many years.

William Wallace Kimball was a farmer from Maine who moved west to Chicago in 1857 in search of adventure, opportunity, and riches. He bought a piano retailing store but lost everything in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Although Kimball knew little about music and less about pianos, he had a strong head for business, saw his chance, so he began selling pianos again. In no time at all he had his own thriving piano manufacturing business. Kimball concentrated on cheap yet fairly high-quality pianos and parlor organs. He was able to market his product because he had established a superb selling organization before going into independent business. By 1915 Kimball was the largest piano manufacturer in the world.

By 1880 upright pianos had totally displaced the larger square piano. The upright took up less room in the parlor than the older style, and it had a much better sound quality. The square piano usually did not have an iron frame, severely limiting its string tension. Square pianos also had a tendency to twist up into contorted shapes after 10 years or so due to heavy string pressure and constant changes in humidity.

The going price for a good piano was $800 to $1200 dollars, a sum that was out of the reach of most middle-class wage earners. New parlor organs could be purchased for $200, and cheap pianos sold in the $200- to $300-dollar range, which was equivalent to about 9 months’ wages or the price of a car in today’s economy. For poor people who made less than a dollar a day, the purchase of a new parlor organ or cheap piano was still out of the question. A beat-up, used square piano could be had for $30 to $60, but even that was a lot of money. However, a used parlor organ could be obtained at a bargain, for $20, a price that just about anyone could afford. Thus it is fair to say that for the first time in history, a keyboard instrument was within the reach of almost every American family.

Dealers were frequently willing to offer their customers attractive

installment payments to make a sale. A new $265-dollar piano could be purchased for $25 down and $10

dollars a month for two years. [10]

Dealers also resorted to raffles, give-aways, and

auctions--anything that would attract buyers. Salesmen would do anything, say anything, and go to any lengths,

all in the true American tradition of fast-talk, hard-talk, and

double-talk. Some dealers

went so far as to describe pianos as “Repeating action rail, duplex bridge with auxiliary vibrators,

telescope lamp bracket, and automatic music desk.” [11]

Or “Patent grand plate and scale, patent touch regulator,

patent grand fall board, patent harmonic scale, and patent piano

muffler, patent endwood bridge, patent finger guard, patent steel action

frame, patent cylinder top and tone reflector.” [12]

Techno-babble was alive and well long before computers made their

debut.

Dealers were frequently willing to offer their customers attractive

installment payments to make a sale. A new $265-dollar piano could be purchased for $25 down and $10

dollars a month for two years. [10]

Dealers also resorted to raffles, give-aways, and

auctions--anything that would attract buyers. Salesmen would do anything, say anything, and go to any lengths,

all in the true American tradition of fast-talk, hard-talk, and

double-talk. Some dealers

went so far as to describe pianos as “Repeating action rail, duplex bridge with auxiliary vibrators,

telescope lamp bracket, and automatic music desk.” [11]

Or “Patent grand plate and scale, patent touch regulator,

patent grand fall board, patent harmonic scale, and patent piano

muffler, patent endwood bridge, patent finger guard, patent steel action

frame, patent cylinder top and tone reflector.” [12]

Techno-babble was alive and well long before computers made their

debut.

Fierce trade wars were carried on, not just by the retailers, but by the manufacturers themselves. In 1878 the English actor James Mapleson brought his company to New York for a series of performances, and he was, as expected, generously supplied with Steinway pianos. It was very good advertising. When the performing company moved to Philadelphia the next year, they were again treated to Steinways; but this time the local piano manufacturer, Allen Weber had other ideas. He sent his loading crew into the hotel, and they threw out all the Steinways and replaced them with Webers. When Steinway found out, he decided to send his own crew back in to replace the Webers, but the Weber people would have none of this and were waiting for them, piano legs in hand. Needless to say, by the end of the struggle more was broken than just piano legs. The Philadelphia piano people won the day and banished the Steinways all the way back to New York.

But perhaps the biggest incident involving piano competition occurred during the Chicago World’s Fair. [13] Chicago was Kimball territory, and by a series of complicated political shenanigans, the Kimball Company managed to get Steinways excluded from the fair. This presented a big problem because many of the famous artists refused to perform on anything other than Steinways. Therefore the Steinway people had to smuggle a few of their own pianos into the fair to satisfy the performers who would not play otherwise. The pianos were carefully and surreptitiously brought in under cover of darkness, with tape over their labels to keep the Kimball people from discovering the ruse and ther throwing the pianos out of the fair, as they had threatened to do. Performances went as scheduled and no Steinways were thrown out.

In 1887 there were relatively few piano students. At the Music Teachers’ National Association’s meeting in 1887, a spokesman for the association publicly offered an estimate probably 500,000 piano pupils existed in the entire United States. [14] This was a pathetic figure when you consider that about 20 million people were within the piano-lesson age bracket (between seven and twenty). This means that only one youngster in forty was actively practicing piano, or about 2½ percent of the potential piano-playing population. The teachers felt this was not at all good for business, and something just had to be done. Piano teachers began to mobilize because they recognized the huge potential market just waiting to be tapped.

By

1902, a mere fifteen years later, a completely different picture had

emerged. American

expenditures for music had reached $593.5 million. Of this amount, only 27 percent was spent on pianos while 37

percent went for piano lessons and music courses. At the same time only $60 million was spent on talking machines

and records. [15] This means that ten times the money spent on records was being

spent on piano lessons, pianos, and parlor organs. In 1913 a survey of every public school in Hartford,

Connecticut revealed more interesting trends. 29

percent of all girls were taking private piano lessons, and 11 percent

of all boys. In other words,

20 percent of all grade school students were actively taking piano

lessons. In high school

things looked even better for the piano. A full 57 percent of all high school children studied music privately, and

of these, 78 percent chose to study piano. [16]

By 1919 the trend began to turn downward. Nonetheless, in that year another survey revealed that 43 percent

of junior high and 49 percent of high school students studied piano

through private lessons--still considerable. 73

percent of the homes of all junior high school students had pianos, as

did 66 percent of the high school group.[17]

The piano teachers had accomplished their goals.

By

1902, a mere fifteen years later, a completely different picture had

emerged. American

expenditures for music had reached $593.5 million. Of this amount, only 27 percent was spent on pianos while 37

percent went for piano lessons and music courses. At the same time only $60 million was spent on talking machines

and records. [15] This means that ten times the money spent on records was being

spent on piano lessons, pianos, and parlor organs. In 1913 a survey of every public school in Hartford,

Connecticut revealed more interesting trends. 29

percent of all girls were taking private piano lessons, and 11 percent

of all boys. In other words,

20 percent of all grade school students were actively taking piano

lessons. In high school

things looked even better for the piano. A full 57 percent of all high school children studied music privately, and

of these, 78 percent chose to study piano. [16]

By 1919 the trend began to turn downward. Nonetheless, in that year another survey revealed that 43 percent

of junior high and 49 percent of high school students studied piano

through private lessons--still considerable. 73

percent of the homes of all junior high school students had pianos, as

did 66 percent of the high school group.[17]

The piano teachers had accomplished their goals.

A big change had taken

place in a short space of 15 years. Piano teachers, educators, retailers, and the piano industry, by

developing a public need, by fostering an expectation, and by working on

the sentimentalities and the whimsical and changeable nature of the

American public, had created an interest in piano playing that today

would be considered nearly impossible to achieve.

A big change had taken

place in a short space of 15 years. Piano teachers, educators, retailers, and the piano industry, by

developing a public need, by fostering an expectation, and by working on

the sentimentalities and the whimsical and changeable nature of the

American public, had created an interest in piano playing that today

would be considered nearly impossible to achieve.

A common problem with selling pianos was the high degree of skill needed to play. For a long time, retailers had been complaining that something needed to be done to improve learning methods. American ingenuity was quick to come to the rescue of not only the retailers, but also the many students struggling in pain and desperation to master the infernal instrument. In the late 1880’s Theodore Presser developed a contraption for young piano players that he said almost guaranteed that they would learn the correct hand position. The device was called a “Dactylion.” It forced the wrist into a vice and each finger into a tight ring supported by a set of metal rods curving over them. [18] Even though it was sold for a modest price, for obvious reasons it did not do well.

Another training device

called the “Manumonium” sold for $10.00. It was an apparatus with five keys that could be adjusted for

width and touch. There was

also a pocket hand exerciser available, with finger loops and long

rubber bands supported from the floor by means of a foot stirrup.[19]

Then along came the “Technicon,” a wondrous complex of

rollers, springs, levers, screws, and counterweights that apparently

would help young pianists to develop strong hand muscles.

Another training device

called the “Manumonium” sold for $10.00. It was an apparatus with five keys that could be adjusted for

width and touch. There was

also a pocket hand exerciser available, with finger loops and long

rubber bands supported from the floor by means of a foot stirrup.[19]

Then along came the “Technicon,” a wondrous complex of

rollers, springs, levers, screws, and counterweights that apparently

would help young pianists to develop strong hand muscles.

None of these contraptions met with any commercial success. However, one learning device that did do fairly well was the ‘Practice Clavier” which was essentially a silent piano that had some other training features. In today’s world it could be compared to wearing earphones when practicing. In this way nobody else would have to listen to or be distracted by the bad sounds.

A truly

ingenious device developed at this time was designed to simplify piano playing.

It was called the

Jankò keyboard. It was

invented by the Hungarian mathematician Paul Von Jankò who decided to

arrange the keyboard so as to make all key positions the same. This means you could play in the key of A flat with the same hand

position as you could in C major. He

also reduced key size because there were no black keys to get in the way

of the fingers. In this

manner even the smallest hand could do an octave spread of 5 inches

instead of the customary 6 ½ inches.[20]

Those who learned the Jankò piano became ardent supporters

because they felt it was much easier to play. It appeared obvious that the device was a great improvement;

however, just as with the many improvements of the typewriter keyboard,

the accumulated pressures of

A truly

ingenious device developed at this time was designed to simplify piano playing.

It was called the

Jankò keyboard. It was

invented by the Hungarian mathematician Paul Von Jankò who decided to

arrange the keyboard so as to make all key positions the same. This means you could play in the key of A flat with the same hand

position as you could in C major. He

also reduced key size because there were no black keys to get in the way

of the fingers. In this

manner even the smallest hand could do an octave spread of 5 inches

instead of the customary 6 ½ inches.[20]

Those who learned the Jankò piano became ardent supporters

because they felt it was much easier to play. It appeared obvious that the device was a great improvement;

however, just as with the many improvements of the typewriter keyboard,

the accumulated pressures of

traditional

playing and teaching methods and the opposition of piano instructors and

manufacturers were too much to overcome. The Jankò keyboard was soon relegated to the scrap heap.

traditional

playing and teaching methods and the opposition of piano instructors and

manufacturers were too much to overcome. The Jankò keyboard was soon relegated to the scrap heap.

Despite

all this renewed focus on learning piano, retailers continued to feel

that sales were hindered by the lack of people who could play. What’s more, many who had acquired their piano skills already

had pianos or parlor organs and saw no need to buy new merchandise to

replace the ones that worked fine. American ingenuity again came to the rescue of

dealers and at the same time, the many suffering piano students. The answer to the skill problem came in two forms, the player

piano (or automatic piano), and the Pianola.

Despite

all this renewed focus on learning piano, retailers continued to feel

that sales were hindered by the lack of people who could play. What’s more, many who had acquired their piano skills already

had pianos or parlor organs and saw no need to buy new merchandise to

replace the ones that worked fine. American ingenuity again came to the rescue of

dealers and at the same time, the many suffering piano students. The answer to the skill problem came in two forms, the player

piano (or automatic piano), and the Pianola.

The player piano, invented around 1880, was equipped with a pneumatic device that passed a paper music roll over an array of holes and activated the corresponding keys. All you had to do was go shopping and buy a piano roll containing a song of your choice, load it into the machine and start pumping on the bellows with your feet. Sounds of the great masters immediately filled the parlor, and you were envy of the neighborhood. The player piano, in effect, became the first commercially successful version of recorded music.

The

Pianola, on the other hand, was targeted for people who already had

pianos and saw no need to get rid of their perfectly good merchandise.

This gadget was a large, cumbersome pneumatic device that could

be moved up to the keyboard on a piano. It contained an array of padded fingers that exactly matched the

piano keyboard over which they had to be positioned. It sat there next to the piano like a huge parasite manipulating keys

according to the music roll and making beautiful music.

The

Pianola, on the other hand, was targeted for people who already had

pianos and saw no need to get rid of their perfectly good merchandise.

This gadget was a large, cumbersome pneumatic device that could

be moved up to the keyboard on a piano. It contained an array of padded fingers that exactly matched the

piano keyboard over which they had to be positioned. It sat there next to the piano like a huge parasite manipulating keys

according to the music roll and making beautiful music.

And this is not to say that the public overwhelmingly welcomed these inventions. On the contrary, the many music purists, music teachers, educators, ministers, and even some piano makers who had not developed similar products strongly condemned these apparently so called advances in music development. John Philip Sousa was perhaps the strongest advocate against these new contraptions, claiming that the devices deprived us of our fundamental ability to be creative, de-personalized music, and were a general disgrace to the art itself, being perpetrated by the manufacturers solely out of crass commercialism and petty profit.

In one respect the introduction of player pianos and the Pianolas actually may have even hastened its demise. The industry was, in a way, hoist by its own petard,[21] for the attractiveness of automatic music only whetted public appetite for more varieties of recorded sound; and sure enough, the invention of records soon became a frightful reality.

But the player piano and its little brother, the Pianola, had its day of glory--however brief. The following chart indicates that the player-piano movement reached its peak around 1919, apparently at the expense of regular pianos, and then gradually faded away into obscurity.[22]

|

Year |

Pianos (1,000) |

Automatics(1,000) |

|

|

|

|

|

1900 |

171 |

6 |

|

1009 |

330 |

34 |

|

1914 |

238 |

98 |

|

1919 |

156 |

180 |

|

1925 |

136 |

169 |

|

1929 |

94 |

37 |

The player piano was a last-ditch effort on the part of manufacturers to retain their huge market share, which gradually began to erode after 1910 mostly because of recorded music. Sheet music sales suffered the same fate since the two were so closely connected.

We see the clear and true American marketing spirit at work around the turn of that century represented by the incredible growth of the piano industry. Never again would piano sales be as robust as in 1909, nor would there be a keener excitement or enthusiasm on the part of Americans to learn how to play piano.

Thus

it has become our legacy. Many

of our sons and daughters slaved away at the keyboard learning scales,

tempos, rests, treble clefs, and base clefs. The boys made up stories and joked in schoolyards about

“all cows eat grass,” “good boys do fine always,” and

“farts are changing everyone” and made other rude cracks about memory joggers used by well-intentioned

music teachers.

Thus

it has become our legacy. Many

of our sons and daughters slaved away at the keyboard learning scales,

tempos, rests, treble clefs, and base clefs. The boys made up stories and joked in schoolyards about

“all cows eat grass,” “good boys do fine always,” and

“farts are changing everyone” and made other rude cracks about memory joggers used by well-intentioned

music teachers.

But piano playing offered new opportunities. Young girls who wanted to be more than housewives and schoolteachers had a new tool for self-improvement--music through the piano. Many of these same young people who moved eagerly into the bright new century brought more than their piano playing skills. They brought a uniquely new form of music-- American popular music. These young piano players had to learn piano pieces from the stuffy classical world. They did this so their parents could be proud of them, knowing their parents wanted to give them things that they themselves never had, such as a good education in classical music skills, a sure-fire path to success. The new generation was expected to play all the old masters: Beethoven, Bach, Schubert, Chopin and Mozart.

Instead, on Saturday nights the young people did what they wanted to do. They gathered in someone’s parlor and played modern risqué music and low brow Tin Pan Alley drivel like Cuddle Up a Little Closer, I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now, Hello, My Baby, or Bedillia, I ‘Wanna Steal ‘Ya, or any of a thousand other cheap, 10-cent songs. Kids could go down to F.W. Woolworth or the corner drug store or the barber shop and browse through the set of racks containing the latest in pop music, anything from Mansions of Aching Hearts to Let Me Call You Sweetheart. There were no ratings, restrictions, or other parental controls on these apparently disgraceful and shameful products. Young kids could look at the covers of this lurid and suggestive sheet music, which often contained pictures of girls with their hair down, and read the scandalous lyrics inside. Kids could buy the deplorable stuff and bring it home under their sweaters or knickers, away from the eyes of suspicious and meddling parents, and ask their older sisters to play the degenerate material. And such was the deplorable state to which America’s youth had fallen. This, of course, was all from the perspective of a judgmental and harsh Victorian society which was unwilling and probably unable to accept pop and ragtime music anyway.

By the end of 1910 there were well over 6 million pianos in the country and probably as many parlor organs, being shared by about 13 million households. America was a singing country. Sheet music sales reached a peek that year. In 1914 everyone was dancing. It was time alive with song and dance.

For two decades starting in 1892 pianos reigned supreme. Without it there could be no sheet music industry, no Tin Pan Alley, no slow waltzes, no two-steps, no ballrooms, and no turn-of-the-century America as we remember it. None of this music could have come to pass without millions of pianos, each playing away late into the hot balmy moonlit nights in a hundred cities across this country. And it was the young people who sang and who learned to play. These were the people who would go into the future, the 20’s, the great depression, two great wars, and would be sustained by the songs they listened to and sang and played when they were young. During this time pianos were the soul of America, the lifeblood, the fifth element, the great unifier. This musical instrument, invented by Italians, developed by Germans, and finally perfected by Americans, even now as we reflect back through history, stands out as one of the strongest symbols of that time.

She: "What do you think of his execution?"

He: "I'm in favor of it."

L.H. Townsend, 1907.

Here are some other links in this article:

Origins of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

[1]

Roger Lewis & Lucien Denni, Oceana

Roll, 1911.

[2]

Mary Blocksma, The Marvelous

Music Machine: A Story of the Piano (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall,

Inc., 1984), 36.

[3]

Cyril Ehrlich, The Piano

(Oxford: Clairendon Press, 1976), 128.

[4]

Ehrlich, 129

[5]

Ehrlich, 131

[6]

Arthur Loesser, Men, Women and

Pianos: A Social History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954),

561.

[7]

Some universities today require students in their elementary

education teaching program to take and pass a keyboard class to get

a degree.

[8]

Loesser, 549.

[9]

Loesser, 564.

[10]

Loesser, 570.

[11]

Loesser, 555.

[12]

Loesser, 555.

[13]

It was officially called the World’s Colombian Exhibition,

celebrating 400 years since the discovery of America, but everybody

today, as then, called it the Chicago World’s Fair.

[14]

Loesser, 540.

[15]

Craig H. Roell, The Piano in

America, 1890-1940

(North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 186.

[16]

Roell, 187.

[17]

Roell, 187

[18]

Roell, 541. Reprinted by

permission.

[19]

Roell, 541.

[20]

David Crombie, Piano (San

Francisco: Miller Freeman Books. 1995), 68.

[21]

Destroyed by its own device.

[22]

Ehrlich, 134.