Ha

Ha Ha Ha Ha[1]

Ha

Ha Ha Ha Ha[1]Dominic Vautier 4/22/11

Ha

Ha Ha Ha Ha[1]

Ha

Ha Ha Ha Ha[1]

Marshall McLuhan [2] stated that the media, by its nature, has a way to influence the message-so much so that the media becomes part of that same message. A good example was TV news coverage of dying and suffering Vietnamese children fleeing a napalmed village while American GIs stand by and watch in silence and disgust. The same incident when reported on page twenty-three of The New York Times just may not elicit the same reaction.

There are many ways that media can change the message. Another famous example was Orson Wells’ War of the Worlds, which was broadcast by radio in 1939. The awesome power of radio became quite clear. Then too, with the advent of color TV, the tobacco companies used young fair-skinned girls puffing on cigarettes to advertise products, a media message that became quite successful.

The

early part of the last century (1900-1915) experienced a similar media event.

It witnessed the powerful use of media with Gibson Girls playing pianos, riding bicycles, and more significantly, walking

around with portable record machines.

The

early part of the last century (1900-1915) experienced a similar media event.

It witnessed the powerful use of media with Gibson Girls playing pianos, riding bicycles, and more significantly, walking

around with portable record machines.

This subtle introduction of recorded music may have had every bit as profound a change as could be imagined, for it started one of the big cultural shifts that was occurring in entertainment at that time and continues to this day. As recorded music evolved and its quality improved, it also affected the way music was interpreted. Instead of just small-town talent demonstrating a song on piano at local barber shops, a big-name artist could interpret the music and make it something more their own. The general public soon become awed, and only those with great talent would feel adequate enough to perform the music once a recorded version was available.

Music became less personal in a way. The average Americans who once were casual performers of sheet music became recipients of recorded music. The customer’s position shifted from active participation to passive listening, from a performer--of whatever talent--to a bystander. The parlor became a place of spectator entertainment (a forerunner of the TV dominated living room), instead of active and creative. A requirement for personal contribution no longer existed for the music experience. Music became background, arbitrary, and coincidental, and often too, a justification to become isolated. To enjoy this kind of slightly different music, people needed only to have a slight curiosity or a casual interest. Involvement no longer required special talent or effort, such as being able to sing, play piano, or read music. Instead of needing someone with a piano and the ability to use it, one needed only to have the money to purchase records and a playing machine. Music had become available to everyone, regardless of personal contacts or education. It became democratic, or maybe communistic?

Because of this trend, pianos sales declined rapidly after 1915 despite the piano industry’s every attempt to retain its diminishing sales. In desperation the industry introduced player pianos, Pianolas, and other devices, but nothing would help because America had already seen what recorded music could do and they liked it. Americans were moving in the direction of passive modern downloadable entertainment.

I

can identify five technological advances in popular music. The first, and most significant

by far, occurred around 1915 when the

industry moved from its long-standing traditional sheet-music format to acoustic

recording. This was a gradual

process that took many years because the phonograph needed a generous gestation

period. It

also took an unusually long time for all the various manufacturers and competitors to come to

terms with each other and agree on record manufacturing standardization.

Then there was the public acceptance of this media as

being something more than simply a novelty or a toy for the rich.

By 1915 records had truly arrived. The sales gap between sheet music and recorded music had closed, and 1915

was the first year that records out-sold sheet music, a trend that would and could never be reversed.

I

can identify five technological advances in popular music. The first, and most significant

by far, occurred around 1915 when the

industry moved from its long-standing traditional sheet-music format to acoustic

recording. This was a gradual

process that took many years because the phonograph needed a generous gestation

period. It

also took an unusually long time for all the various manufacturers and competitors to come to

terms with each other and agree on record manufacturing standardization.

Then there was the public acceptance of this media as

being something more than simply a novelty or a toy for the rich.

By 1915 records had truly arrived. The sales gap between sheet music and recorded music had closed, and 1915

was the first year that records out-sold sheet music, a trend that would and could never be reversed.

Five years later the record industry made its first big breakthrough when electronic sound recording replaced the older acoustic recording methods. The transducing devices, electronic microphones, amplifiers and record cutters, produced greatly improved sound quality and slightly improved frequency response.

It was pure magic for the record cutting process. The cutter is a device that actually cut waveform into a movable surface. The cutter was initially driven acoustically, that is, by a diaphragm driven by actual air generated by singers and sound instruments, and this took a lot of energy from singers and musicians as I will discuss below. When the cutter was driven electronically an microphone delivered variable amounts of electricity to magnetic coils that drove the cutter which allowed musical artists to perform naturally.

After that time there were numerous incremental technical improvements, the most important of which was tape recording developed by the Germans during WWII, and microgroove record cutting in 1947, which used a long-playing 12-inch vinyl record and a much smaller groove. The smaller groove, combined with use of vinyl material, allowed for much smaller grove wiggles and therefore higher frequency response. In fact, the smaller and highly improved playing cartridge (needle) often boasted of a frequency range of 20 to 20,000 CPS (cycles per second), which exceeded the capacity of most human ears. The LP could also play up to 25 minutes on one side.

Microgroove recording marked the real beginning of true high-fidelity music, which meant that sound became very true to life. But the term “hi-fi” was soon generalized, applying to just about anything that produced half decent music. It could refer to the cheapest import or the most expensive professional equipment because people did not notice the difference that much. It all sounded pretty good.

During the period of transition from 1950 until 1962, records came to be known by their turning speed or RPM (revolutions per minute). The older style records had a speed of 78 RPM more or less, which had been established in the early years. By 1955 the older style “breakable” shellac records became known as 78s. The LP (long playing) was an album and contained many songs. It turned at 33 1/3 RPM and was called a 33. Sometime around 1970 it became known as an LP.

To continue the tradition of single-record production, RCA produced another type of record known as the 45. Also a microgroove, it sounded almost as good as the larger 33 1/3-RPM record. The 45 was distinguished by its large center-hole, which was used primarily for jukeboxes. It eventually lost out to the more ubiquitous LP even though it continued to be used for some time.

Finally, in 1982 the compact disk (CD) arrived, and its sound quality was as good as the human ear. It was smaller, easy to handle, and much more convenient to carry. Stores could stock more selections because CD’s were smaller, but then, for that same reason, more theft occurred, and security devices were needed. More playing time was available with digital media, so all of Beethoven’s third symphony could fit on one CD. The digital quality was probably as good as you could get, but most important of all, the new media was more robust. It could effectively compete with cassettes because it was small enough to be used in cars and just as impervious to road vibrations. For a time the CD replaced the LP market but destroyed the cassette and 8-track market.

Other improvements in sound represented minor breakthroughs involving more obscure technical aspects. Such things as frequency response, signal-to-noise ratios, harmonic distortion, rumble, wow and flutter, anti-skating are terms that are beyond the scope of this discussion yet are very important and meaningful to people who devote their interests to collecting music. This host of technical terminology describe various recording and playback characteristics that were improved upon during the history of recorded music and remain important to record collectors.

Stereo came in around 1954 soon after the advent of “hi-fi”. The idea behind stereo was to give the effect of three-dimensional sound by maintaining two separate channels, each with its own sound track. This simulated the human experience of three-dimensional hearing. An independent sound source could arrive at each ear at slightly different times, but more important still, the sound sources themselves were different, reproducing a musical panorama of sound presented before the very ears of the listener. Stereo was accomplished by combining the zigzag and hill-and-dale groove-tracking techniques, that is by rotating the recording path 45 degrees and cutting a v-shaped track so that each side of the record groove wall became a signal with its own set of wiggles. This created two separate “channels” that could carry independent sound tracks. With tape recording devices the signal was simply carried on two separate tracks.

The above discussion is intended to illustrate the close and unique relationship that America has had with devices that produce music. Although most of this activity occurred after 1915, the foundation of what we have and cherish today as part of our musical tradition was laid down from for us in the formation years of 1892 until 1915.

In 1866 a Frenchman named Leon Scott discovered how to record a sound wave on a paper medium. This breakthrough discovery in sound recording occurred after much experimentation and resulted in actually being able to capture the image of a sound wave.

Scott had studied the human ear and decided that, if he could make a replica, he may be able to reproduce the sound of speech. He had a good idea of just how sound waves worked, so Scott began with a diaphragm that would vibrate when sound fell upon it, just like the eardrum did. Scott then connected a wire to the diaphragm and a small brush to the end of the wire. He blackened a piece of paper with carbon soot. He then moved that piece of paper under the brush and spoke at the same time. His voice was recorded as a wave line. Scott was the very first person to see what a sound wave looked like.[3]

Sound waves could thus be measured and analyzed. More important, they could actually be captured and seen and and saved. Scott had, in a sense, finally discovered the Philosopher’s Stone, the magic stone that could turn base metals into gold, the ultimate dream of alchemists. He could grab a sound out of thin air and turn it into something physical.

During

the next ten years another Frenchman, Charles Cros (Croi), worked toward making an even

more valuable contribution. He

developed a way not only to record sound waves, but also to play them back and

even reproduce them. Cros based his

thinking on the work of Leon Scott and American inventor Alexander Bell, as well

as his own extensive knowledge of chemistry and photography. By the end of 1876 Cros had come up with the first workable and practical

way to record and reproduce sound.[4]

During

the next ten years another Frenchman, Charles Cros (Croi), worked toward making an even

more valuable contribution. He

developed a way not only to record sound waves, but also to play them back and

even reproduce them. Cros based his

thinking on the work of Leon Scott and American inventor Alexander Bell, as well

as his own extensive knowledge of chemistry and photography. By the end of 1876 Cros had come up with the first workable and practical

way to record and reproduce sound.[4]

Cros reasoned that if a cutting stylus replaced the brush, then it would cut a

wiggly groove instead of just leaving a mark. A playing device connected to a diaphragm could then follow the groove

and reproduce sound. For longer

recordings, Cros planed to use a device that could turn a flat disk on a table.

Cros then described, in amazingly accurate detail, how a modern

phonograph was to work. He published

his paper in April of 1877, almost a year before

Edison was unaware of this research activity going on in France, and he came upon the whole sound-recording thing independently and completely by accident. He was, at the time, more interested in working out a way to repeat telegraph messages.

He

slipped a piece of indented paper beneath a telegraph. The telegraph had a loose spring dangling from it and as the paper rubbed

against the spring,

He

slipped a piece of indented paper beneath a telegraph. The telegraph had a loose spring dangling from it and as the paper rubbed

against the spring,

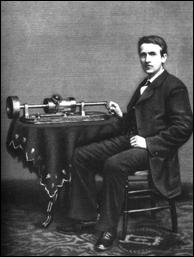

Some weeks later when the machine was finished, Edison looked it over, wrapped some tinfoil around the drum, inserted the cutting stylus, and began cranking and shouting “Mary had a Little Lamb” into the horn. He replaced the cutting stylus with a playback stylus, repositioned the cylinder, and began cranking. His voice came back loud and clear. For perhaps the very first time in his life, Thomas Edison was absolutely astounded and in fact almost in shock. He didn’t handle surprises very well and thereafter was always somewhat suspicious of this invention that had been so easy to design. It caught him badly off guard by actually working the first time. Inventions were not supposed to do that, so there had to be something wrong with this one.

For the next ten years Edison did little or nothing with his gadget, even though he felt that the recording device had some kind of commercial application. Instead, it took some breakthrough technology from elsewhere to finally spur the inventor back into action.

Alexander Bell, along with his cousin Chichester Bell and a young assistant Charles Tainter, formed a research team called the Volta Group. This research team began to improve on sound recording by cutting a groove into a surface rather than denting tinfoil as Edison had done. This was the same idea that Charles Cros had suggested years before. The Volta group patented the zigzag approach to sound reproduction, where a stylus moved back and forth following a square groove on the recording surface, as opposed to Edison’s hill-and-dale technique where the stylus tracked up and down to generate sound. Another contribution from the Volta group was a free-floating stylus or needle that was driven by the groove itself rather than a tracking screw. This free-floating feature brought about a definite improvement in sound quality. The Volta Group evolved into the American Graphophone Company and immediately began to market their first product, the famous, though not too successful, Graphophone.

Edison quickly made up for lost time. He seized upon Tainter’s ideas and improved on some of his own. He installed a solid wax cylinder in his recording machine. When done recording, the user could simply shave off the wax and begin recording again on a new surface. Edison also installed a battery-powered motor to drive the cylinder. He then formed the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company to sell his new product. The machine did sell well to court recorders and stenographers, but the technology was still by no means good enough for music. In 1888 the American Graphophone Company and the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company together formed a third company called the North American Phonograph Company.

Even though product sales were sluggish, an enterprising young salesman

from The Pacific Coast Phonograph Company, a subsidiary of the Edison Phonograph

Company, had made nearly all his profits from the entertainment business. He rigged up a coin slot on several machines so that people

paid a

nickel to make them play. He then

developed a collection of music and humorous stories.[5]

1890 marked the first use of this nickelodeon, an entertainment device

that would take the country on a wild ride over the next 15 years and cause a

never-ending controversy about social responsibility and the corruption of youth

by these evil and morally degrading devices. The forerunner of the jukebox

and video game had arrived.

1891 was the year that phonographs were first offered to the general public. The Columbia Phonograph Company sold its phonographs records not just to businesses but to anyone who wanted to buy. It was the first time that a record machine was offered for home entertainment,[6] even though there was not very much entertainment music available.

Emile Berliner was born in

Germany

in 1851 and emigrated to the

United States

in 1870.[7] He invented the microphone for Alexander Bell and later turned his

attention to the problems facing the emerging recording industry. The first thing he noticed was that the recording cylinder would never

do, and decided that the only successful recording medium was a flat rotating disk.

Cylinders were too fragile and bulky, hard to transport, difficult to

store, and most important of all, they were hard to mass- reproduce.

The future of records was to be a flat disk, just

as Charles Cros had years before suggested in his phonograph design work.[8]

Berliner realized that Edison’s wax cylinder could be erased and reused, but he was focusing his attention

on a market for prerecorded permanent music. Berliner

also realized that the “zigzag” method of recording was far better than the

“hill-and-dale” method. A stylus

could track much better since it was controlled from both sides of the groove

instead of just the bottom where it could bounce too much.

the wiggle grove was also less susceptible to external vibrations and produced a

cleaner sound.

reproduce.

The future of records was to be a flat disk, just

as Charles Cros had years before suggested in his phonograph design work.[8]

Berliner realized that Edison’s wax cylinder could be erased and reused, but he was focusing his attention

on a market for prerecorded permanent music. Berliner

also realized that the “zigzag” method of recording was far better than the

“hill-and-dale” method. A stylus

could track much better since it was controlled from both sides of the groove

instead of just the bottom where it could bounce too much.

the wiggle grove was also less susceptible to external vibrations and produced a

cleaner sound.

Problems confronting Berliner were many. Nobody had been successful at recording on a flat disk before, so he had to develop not only a system that used the flat disk, but also zigzag tracking. Then he had to come up with a way to mass-produce disks. Copies had to be as close as possible in quality to the master, and he had to be able to make many copies quickly. And of course, there was always a constant threat of expensive lawsuits over patent infringement, which could suck the life and resources out of any start-up venture. All of these were daunting challenges for this young inventor.

After some false starts, Emile finally was able to come up with a way to reproduce his disks. He took a flat zinc plate and coated it with a mixture of wax and benzene. He then placed it on the recording machine where the cutter scratched a sound line. The zinc plate was then immersed in chromic acid, which ate away the exposed metal, leaving a groove. He could even make a deeper groove by keeping the plate in the acid longer. A deeper groove would allow a stylus to track without any tracking screw, which was needed with softer wax grooves since the wax itself was too soft to move the needle. Once a master plate was produced, he was then able to mold from it a second metal disk or “stamper” with raised edges instead of grooves. From this stamper he could make many reproductions, and these sounded almost as good as the master. The general method of record reproduction invented by Emile Berliner was never really superseded. It remained basically unchanged for the next 100 years, that is, until records were no longer made.

Berliner

called his device the gramophone and formed a company called the American

Gramophone Company. He was able to

sell gramophones and records for less than the competition, and his business

began to grow. Edison, as was his custom, fought back, throwing his huge influence, wealth, and

prestige behind his own phonograph.

Berliner

called his device the gramophone and formed a company called the American

Gramophone Company. He was able to

sell gramophones and records for less than the competition, and his business

began to grow. Edison, as was his custom, fought back, throwing his huge influence, wealth, and

prestige behind his own phonograph.

It was a vitriolic campaign that ensued. Though certainly not as vicious as the now well-known AC-DC wars waged against Westinghouse, it was in some ways just as intense. Numerous patent suits were filed by Edison. Advertisements proclaimed that Edison’s machine performed better, lasted longer, and had bigger music catalogs. Edison was highly critical of the flat disk, alleging that too much distortion was present and that it could never be properly reproduced. He claimed the stylus could not work without a tracking screw, and that the sound at the edge of the disk could never be the same as the sound at the center. Edison asserted that his machine had better reproductive characteristics, and that he could record as well as play sound.

But in the end Edison lost. People liked the gramophones, and Edison’s market share continued to shrink. By the turn of the century, Edison’s two major competitors, Columbia and Victor, were making disks while he stubbornly kept making cylinders until as late as 1913. By that year Edison no longer had significant market share in an industry that he had practically created. He was just a bit player and would never again attain a share of more than 20 percent of the market--nor would he ever again have the kind of market leadership that he had heretofore exercised.

The period of musical recording from 1900 to 1920 is often referred to as the acoustic age. It is also fondly called the golden age of music, but there wasn’t very much golden about it. Electrical devices to improve quality had not yet been invented, background noise was terrible and frequency response was even worse. It ranged from about 200 to 600 CPS at best and singers sounded like they had colds and wet towels over their faces.

Some instruments recorded well while others sounded bad. Violins were tinny and shallow since most of the rich harmonics and overtones of a violin occur at frequencies above 600 CPS. Trumpets, tubas, and trombones all sounded better. Strong male tenors such as Caruso, Burr, and Dalhart worked very well in this seriously restricted media. Sopranos were very poor recording subjects because they sounded squeaky and scratchy, but altos with hefty voices, such as Ada Jones, did fine. Singers adopted affected singing styles and operatic techniques such as rolling R’s and exaggerating consonants so these sounds could record better. In essence the type of music recorded was determined more by technological limitation than by skill, quality, or singing talent. There definitely was not much gold in early recorded music.

Recording sessions were pure misery. Musicians had to huddle around one or more big acoustic recording horns and get as close as possible to each other. The balance of voice and instrument was based on pure luck, and often the equipment broke down. There was no way to control sound balance or volume or monitor output. The recording sessions were long, hot, and tiring, and the pay was poor. No effective law was in place governing royalties, and often a singer never got to make anything beyond his normal wage.

Record reproduction was another big problem. Early songs could not be mass-reproduced, which meant that musicians had to do a song many times over or do many “rounds,” as they were called. Recording studios sometimes had upwards of 15 recording horns running at the same time. It wasn’t until after the turn of the century that recording studios began regular mechanical reproduction of disks. But cylinders continued to be individually recorded. Some methods were developed to reproduce cylinders but these were slow and yielded copies of inferior quality. By 1910 disk-record reproduction had developed to a point where records had become much more plentiful and much less expensive than the cylinders.

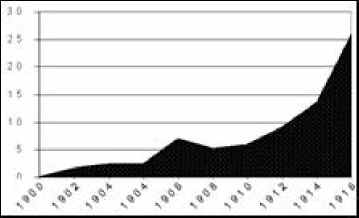

I did this timeline that shows the development of recorded music.

Initially, many companies were making records, all using different standards. By 1900 the industry had consolidated and most of these smaller manufacturers had been bought out. By that time three big record companies controlled 95 percent of the record industry, The National Phonograph Company, founded by Edison in 1896, Columbia of Washington, and the Victor Company.

The Columbia Company was started by Edward Easton. He had previously been employed as a congressional stenographer, and while in this capacity saw the possibilities of recording devices. He formed his own company and bought the rights to the Graphophone, which had been developed by the Bells and Tainter after they completed their work with the Volta Group. Columbia decided to go with both formats, cylinder and disk, but soon--and wisely--dropped the cylinder.

Berliner’s Gramophone Company, charged forward with its popular gramophone, using the technology of zigzag tracking developed by Berliner himself. In 1896 Berliner hired Eldridge Johnson, a talented and enthusiastic engineer, to design and build a spring-driven motor for his record machine. Within a short time Johnson was able to redesign not just the spring mechanism but the entire gramophone. He made many other improvements.

Johnson had a sharp business sense. By 1901 he had taken over Berliner’s company, calling it the Victor Company. It soon became the leader of the American record industry. The Victor Company was the first to recognize the true value and power of recorded music and to invest heavily in the quality and variety of its records. The Red Seal records are one excellent example.

Another employee of Berliner’s Gramophone Company, Fred Gaisberg, opened the world’s first recording studio in Philadelphia in 1896. Berliner’s company virtually pioneered the art of recording. In fact, by 1900, The Victor Company could boast over 5,000 titles in 17 different languages. By 1910, the year after Edison was forced to shut down many of his cylinder plants in Europe, Victor had record manufacturing plants as far off as Latvia and Calcutta.[9]

This chart shows the growth in sales of record machines

Still, to many people, the phonograph

remained a novelty, a toy, an interesting curiosity for rich leisure classes.

In 1904, however, a young Italian singer named Henry Caruso came on the

scene. His strong and vibrant voice

was perfect for recording, and he gave the whole industry a considerable boost.

Caruso recorded several songs that sold very well; in fact one song,

called On with the Motley, sold over a

million records. Although this song

was not popular music (it wasn’t even English), it was, nonetheless, the first

recording to break the million-record mark. The industry had to wait another ten years for the first popular song to

achieve that same destination.

Still, to many people, the phonograph

remained a novelty, a toy, an interesting curiosity for rich leisure classes.

In 1904, however, a young Italian singer named Henry Caruso came on the

scene. His strong and vibrant voice

was perfect for recording, and he gave the whole industry a considerable boost.

Caruso recorded several songs that sold very well; in fact one song,

called On with the Motley, sold over a

million records. Although this song

was not popular music (it wasn’t even English), it was, nonetheless, the first

recording to break the million-record mark. The industry had to wait another ten years for the first popular song to

achieve that same destination.

The challenge that recorded music presented to the prevailing sheet-music industry was a strong one, as is seen by what happened to sheet-music sales after 1915. People who bought sheet music and enjoyed playing it also enjoyed records, and as the cost of records dropped dramatically because of improved manufacturing techniques and mass production, these same people started spending their money on records as well as or instead of sheet music. Recorded music did not have to build a completely new market; it absorbed much of the sheet-music market that already existed.

The advantage records held was obvious. Records preserved sounds, which meant that every accent, linguistic nuance, slur, word pronunciation, dialectic phrase, musical interpretation, change of tempo, and artistic style was frozen on that record, to be enjoyed, examined, analyzed, and studied by current and future generations.

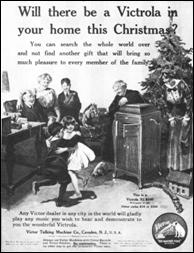

Recorded

sound was also portable. The

early machines were spring driven and required no electricity. They were small and light, and could be easily carried about.

Troops marching off to the long and excruciatingly boring war in

Europe

were encouraged to bring along their Victrolas as a way to keep from going stir

crazy. Big game hunters in far away Africa

spent their evenings among the elephants, monkeys, and mosquitoes, listening to

their record machines, sometimes the only link they had with civilization and

their native language. English outposts in far off

India, half a world away, could relax in their isolated barracks and listen to the

melodious strains of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. Every little dusty, no-name American frontier town had someone with a

record machine playing Daisy Bell and Bedelia all

day. Recorded sound put music on

wheels and gave it a universal appeal that sheet music could never

compete with. It wasn’t a fair

struggle at all. It just wasn’t

the same thing, even though it was the same music.

Recorded

sound was also portable. The

early machines were spring driven and required no electricity. They were small and light, and could be easily carried about.

Troops marching off to the long and excruciatingly boring war in

Europe

were encouraged to bring along their Victrolas as a way to keep from going stir

crazy. Big game hunters in far away Africa

spent their evenings among the elephants, monkeys, and mosquitoes, listening to

their record machines, sometimes the only link they had with civilization and

their native language. English outposts in far off

India, half a world away, could relax in their isolated barracks and listen to the

melodious strains of Gilbert and Sullivan operettas. Every little dusty, no-name American frontier town had someone with a

record machine playing Daisy Bell and Bedelia all

day. Recorded sound put music on

wheels and gave it a universal appeal that sheet music could never

compete with. It wasn’t a fair

struggle at all. It just wasn’t

the same thing, even though it was the same music.

Standardization, brought about mostly under the leadership of the very successful Victrola line of record machines stabilized this young industry. After 1907, other major record companies fell in line behind the recording standards established by the Victor Company. Most disk records could be played on a Victrola machine. It became the unchallenged industry leader. It became the Xerox.

Repeatability,

which allowed more complex music structures, was another advantage in recorded

music. Sheet music, by its nature,

had to be simple and catchy. A cruel

truth about the older music media was if it didn’t catch on after one or

two repetitions by pluggers, it was gone.

Music pluggers knew what would work, and they plugged the songs that they knew would be successes, the songs that were easily

sung by the average consumer and had catchy melodies. But with recorded music, a song didn’t have to be easy to sung, or even

catchy for that matter. It could

play over and over, allowing the public time to appreciate and absorb a more

complex music made available to them.

Repeatability,

which allowed more complex music structures, was another advantage in recorded

music. Sheet music, by its nature,

had to be simple and catchy. A cruel

truth about the older music media was if it didn’t catch on after one or

two repetitions by pluggers, it was gone.

Music pluggers knew what would work, and they plugged the songs that they knew would be successes, the songs that were easily

sung by the average consumer and had catchy melodies. But with recorded music, a song didn’t have to be easy to sung, or even

catchy for that matter. It could

play over and over, allowing the public time to appreciate and absorb a more

complex music made available to them.

Early in the music business, publishers did not see any difference between sheet music and records, reasoning that if a song became popular on sheet music, it would certainly be popular as a record, and vice versa. But publishers quickly found out that things didn't work that way. Sheet music fulfilled a certain set of needs, and this did not assure that a song could successfully jump from one media to another. Sheet music was art in motion, interactive. It required audience participation. It was in your face, up close, and personal. Sheet music had to be composed of a simple melody in a simple tempo, with basic instrumental support so the average player/singer could participate. This did not apply at all to records.

By

1915, a market emerged that wanted to move away from this up-close-and-personal kind of

music. The public wanted an ability

to be less attached to music. They

did not want to have to work in order to enjoy listening to it. They just wanted to be able to turn it on and have it play.

They wanted music in a can. They

wanted switch-on switch-off music. This

different media carried a different message, a message of portability,

simplicity, and repeatability and control. Sheet

music did not carry that kind of message.

By

1915, a market emerged that wanted to move away from this up-close-and-personal kind of

music. The public wanted an ability

to be less attached to music. They

did not want to have to work in order to enjoy listening to it. They just wanted to be able to turn it on and have it play.

They wanted music in a can. They

wanted switch-on switch-off music. This

different media carried a different message, a message of portability,

simplicity, and repeatability and control. Sheet

music did not carry that kind of message.

Whereas people who sold sheet music were not in any way involved in making pianos, recorded music was packaged and marketed along with record machines. The retailers who sold records also sold record machines. In fact, in order to do one, they almost had to do both, so the two technologies (record machine manufacture and record production) were closely bound together and worked in harmony. Pianos and sheet music had long gone their separate ways.

To

be able to play records the investment was small. A good Victrola cost 15 dollars.

Records

were listed at usually one dollar apiece but could be gotten for less. Sheet music was tied to a whole lumbering tradition of pianos, music

instructors, piano teachers and pluggers.

In other words, sheet music was old America. Recorded music represented the new

life, quick-paced, results-oriented, throwaway, portable, and

changeable. Americans were on the

move, and they brought along their record machines, not their pianos.

To

be able to play records the investment was small. A good Victrola cost 15 dollars.

Records

were listed at usually one dollar apiece but could be gotten for less. Sheet music was tied to a whole lumbering tradition of pianos, music

instructors, piano teachers and pluggers.

In other words, sheet music was old America. Recorded music represented the new

life, quick-paced, results-oriented, throwaway, portable, and

changeable. Americans were on the

move, and they brought along their record machines, not their pianos.

Pianos and music instructors were a well-established and standardized industry, but the phonograph was in a constant state of refinement. All this time while the recording industry was trying to settle down, people were waiting for the right time to make a commitment to records, and that time came in 1910, soon after the introduction of the wildly successful Victrola.

The period of about 20 years from 1895 to 1915 was an obscure one when the first wave of recording stars appeared, because these stars seemed to have vanished as quickly as they had come.

Many of these early singers came from vaudeville, Broadway and minstrelsy, and others just happened to be there. Some of them did not make the transition from acoustic recording into electronic recording, being replaced by newer people whose voices were more adaptable to the finer nuances of electronic recording. Others simply wore their voices out under the brutal strain of constant loud singing which was the only way to sing then. Still others drifted into the many offshoots created by this new industry; radio entertainment, radio advertising, sports announcing, sound effects, and radio programming.

Henry Burr is usually recognized as the best known of the early recording greats. With his strong and full-bodied voice, he was said to have done well over 10,000 recordings. He got an early start in 1903, and by the late 1920’s he had begun singing on the radio. Another great was Billy Murray, who worked solo but also did many numbers with Ada Jones and still more songs with the American Quartet. George M. Cohan of Broadway fame, Arthur Collins, Harry MacDonough, Vernon Dalhart, and George Gaskin all made numerous records. Then there were the classical music singers, including the unforgettable Henry Caruso, John McCormick, and Sarah Bernhardt. Not considered exactly primary figures in American music, these early singers are generally remembered only by those who have an interest in early recorded music.

It was a time of very rapid change. Styles, types of music, media, Broadway, Hollywood, all were in flux, and it was very exciting and also very confusing. No wonder this transition time was so easily forgotten. We’d rather remember the big singing stars who came after 1925, when music, media, and the singing styles had settled down.

In

1915, one popular record finally struggled to a million copies, although few noticed

because it took 10 years to get there. The song

was The Preacher and the

Bear, first

recorded by Arthur Collins in 1905 on an Edison

label. You could almost say

recorded music came in with a whimper, but it did not remain a whimper very long because the next year witnessed the arrival of the first

double-sided number-one hit record anywhere. It was Girl on The Magazine Cover

by Harry MacDonough, with the flip side featuring Billy Murray’s Stop,

Look, Listen on a Victor label. By 1920 the record

industry had pretty much destroyed sheet-music along with piano sales. That year the song Whispering

sold 2 million records in about 6

months. Sheet music had only a few

feeble million-sellers after that.

In

1915, one popular record finally struggled to a million copies, although few noticed

because it took 10 years to get there. The song

was The Preacher and the

Bear, first

recorded by Arthur Collins in 1905 on an Edison

label. You could almost say

recorded music came in with a whimper, but it did not remain a whimper very long because the next year witnessed the arrival of the first

double-sided number-one hit record anywhere. It was Girl on The Magazine Cover

by Harry MacDonough, with the flip side featuring Billy Murray’s Stop,

Look, Listen on a Victor label. By 1920 the record

industry had pretty much destroyed sheet-music along with piano sales. That year the song Whispering

sold 2 million records in about 6

months. Sheet music had only a few

feeble million-sellers after that.

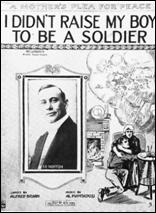

By 1915 the phonograph had asserted itself as media darling. That year alone saw several big sellers. These were not just love songs; they were protest songs, political songs, car songs, drinking songs, and variety songs. These were songs about subjects that couldn’t be fully developed with sheet music. The big hit of 1915 was an isolationist number I didn’t raise my boy to be a Soldier protesting involvement in the Great War raging in Europe.

I didn’t raise my boy to be a

soldier.

I brought him up to be my pride and joy.

Who dares to place a musket on his shoulder,

To shoot some other mother’s darling boy.

Let nations arbitrate their future problems.

It’s time to lay the sword and gun away.

There’d be no war today, if mothers all would say,

I didn’t raise my boy to be a soldier.[10]

The format of early recorded music seems quaint and almost classical to us today but if you listen to enough of it then it tends to grow on you. A good deal of recording time was sometimes dedicated to the song lead-in which stated the main theme of a piece. This short introductory section of music almost seems like an overture to an Opera which summarizes what is to follow. This is demonstrated most well in such songs as Sweet Cider Time when You Were Mine by the Peerless Quartet and All Alone as done by John McCormack. The vocal began with verse then chorus. Often there was only time for two verses within the standard three minute window. The three minute window was dictated by technology because Edison's cylinder was just that big so Victor and Columbia kind of followed suit. During the Big Band era, formats would again revert to a good deal of band lead-in followed by vocal.

Thomas Edison is usually credited with invention of the phonograph, and in fact, he did develop several key patents. But it is fair to question whether the industry would have been better off without him. He was stubborn and intransigent, and he oftentimes exhibited a destructive and unreasonable belief in the infallibility of his own ways. From this behavior, one gets a feeling that, thanks to Mr. Edison’s huge ego, the sheet-music industry enjoyed at least an extra ten years of life before being displaced by a more viable medium.

Edison may have realized the obvious but he had his stubborn boots on. His cylinder record was hard to manufacture, fragile, short-playing, and difficult to copy, store and ship. Had Edison attempted a little market research, which he had done so successfully in other areas, he may have been tremendously influential in music. Nor did he understood that people did not want to buy his “good music.” They wanted “lowbrow” music like Jazz and ragtime. Had he begun cooperating better with the nascent recording industry, throwing his impressive name behind the flat disk format that the other two manufacturers used instead of fighting a constant war over trivial and questionable patent infringements, things might have been different.

Then too, it seems unusual that the invention of recorded sound occurred as late as it did given that it involved no significant scientific breakthroughs or particularly challenging mechanical development. Devices like cylinders, springs, screws, flywheels, stylus, diaphragm, and hand cranks were common and well-established technologies. Recorded sound came into existence in 1877, a good 15 years before popular sheet music even began really blooming. It took another forty years before recorded music was even on a par with sheet music. Given the aggressive entrepreneurial spirit of the last three decades of the 1800's, it is hard to understand why recorded music was so long in coming or why it did not assume a stronger position earlier.

The Victor Dog

But history spins her web in apparently

well-designed ways. Had recorded

music presented itself even 20 years earlier, what then would have happened to

the beautiful chaotic patchwork of songs given to us by the great songwriters of

sheet-music, the era of the Berlins, the Dacres, the Dressers, the Von Tilzers,

the Sterlings, and even Tin Pan Alley itself? But

it did not happen that way. It happened the

way it did. Sheet

music had its great day, and recorded music came along when it was supposed to arrive.

But history spins her web in apparently

well-designed ways. Had recorded

music presented itself even 20 years earlier, what then would have happened to

the beautiful chaotic patchwork of songs given to us by the great songwriters of

sheet-music, the era of the Berlins, the Dacres, the Dressers, the Von Tilzers,

the Sterlings, and even Tin Pan Alley itself? But

it did not happen that way. It happened the

way it did. Sheet

music had its great day, and recorded music came along when it was supposed to arrive.

Here are some other links in this article:

Origins of Early Popular Music

Minstrelsy

Broadway

Vaudeville

Other sources

People Growth - the First Baby Boom and it's effect

[1]

The Laughing Song was recorded by

George W. Johnson beginning in 1891, the first black American to do so.

I say “beginning in”

because he recorded it at least 40,000 times over a period of years. There was no way to reproduce songs then.

You could say he was a happy guy.

[2]

McLuhen was a communications expert who wrote about the power of the media

in his very popular book The Medium is

the Message, (Bantam Books, 1967).

[3]

Bradley Steffens, Phonograph: Sound on

Disk (California: Lucent Books Inc., 1992), 15.

[4]

Steffens, 17.

[5]

Steffens, 38.

[6]

Steffens, 41.

[7]

Peter Martland, Since Records Began:

EMI The First 100 Years (Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1997), 12.

[8]

Martland, 22.

[9]

Michael Chanan, Repeated Takes: A

Short History of Recording and Its Effects on Music (New York: Verso,

1995), 29.

[10]

Bryan & Piantadosi, I Didn’t

Raise My Boy to be a Soldier, 1915.