Cascadia

And

I think of my happy condition,

Surrounded by Acres of Clams.

Lay

of the Old Settler

(Early

Northwest folk song

by The Brothers Four)

Dominic

Vautier

9/17/18

When

I was a little kid living in Everett, Washington I used to go down to the long narrow park on Grand Avenue

a few blocks from where I lived. A

big tree hung out over the steep bluff dangling a sturdy rope, and it was great

fun to grab the rope and swing out into the abyss way over the brambles and

blackberries far below. It was even rumored that a kid had been killed on those bluffs. Today the place is called

Grand Avenue Park.

When

I was a little kid living in Everett, Washington I used to go down to the long narrow park on Grand Avenue

a few blocks from where I lived. A

big tree hung out over the steep bluff dangling a sturdy rope, and it was great

fun to grab the rope and swing out into the abyss way over the brambles and

blackberries far below. It was even rumored that a kid had been killed on those bluffs. Today the place is called

Grand Avenue Park.

An obscure and little noticed park stone was there containing a impressive bronze plaque

which read “ON THE BEACH NEAR THIS SPOT VANCOUVER LANDED, JUNE 4, 1792”.

The plaque is still there and certainly my memory of it is.

Casual

research leads me to wonder why and how Seattle

and Puget Sound ever managed to wind up in the United States, a question that may surprise some but still a very worthwhile question to ask

especially since the British were not much inclined to give up hard fought for

and painfully acquired terratories.

Consider that all this area was explored by the British, settled by the British,

fortified by the British and occupied by the British before we came along. So what happened?

How did we get it?

Casual

research leads me to wonder why and how Seattle

and Puget Sound ever managed to wind up in the United States, a question that may surprise some but still a very worthwhile question to ask

especially since the British were not much inclined to give up hard fought for

and painfully acquired terratories.

Consider that all this area was explored by the British, settled by the British,

fortified by the British and occupied by the British before we came along. So what happened?

How did we get it?

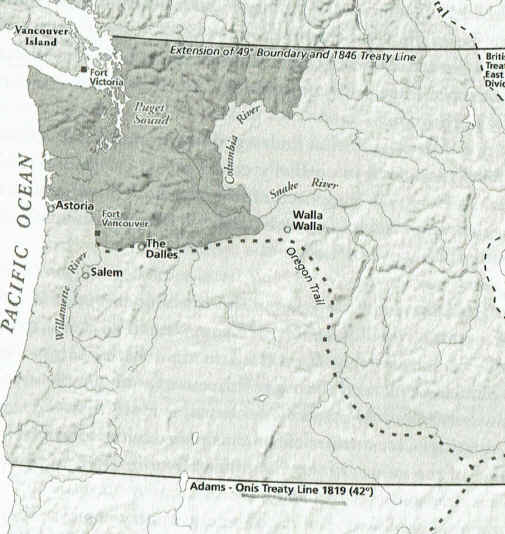

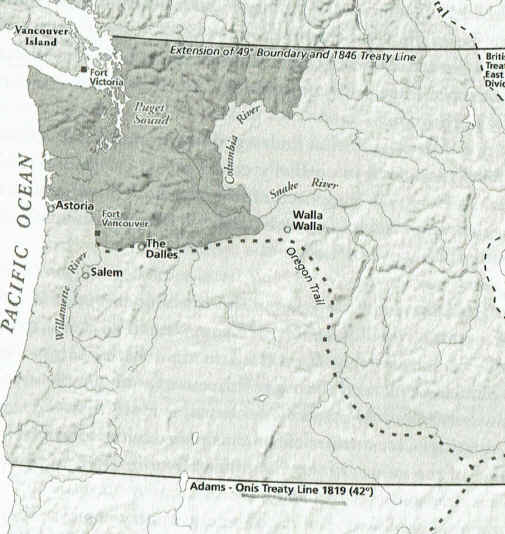

Some

may have a vague recollection that Britain

and the U.S.

extended the 49th parallel because it made good sense and looked

like a clean way to settle a long and festering dispute (which actually makes no

sense--artificial lines never make any particular sense). Also since we had a lot of settlers here and the “54 40 or fight”

rage was at a high peak by 1846, it may have somehow convinced England

to back down and give up all their land and settlements north of the

Columbia River. Not very likely I think. Too wasn’t it somehow our destiny to conquer and own this area of the

Northwest under the so-called oft-preached concept of “Manifest Destiny”?

This may be one way to explain why the British decided to freely gave up

their land, or at least that’s what the history books try to tell us? No, not

quite. I found that there is a more complex story here.

Even

as late as 1840 few Americans actually lived north of the Columbia River thanks

to the continuing efforts of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) to settle the

region, work closely with the Indian populations and occupy all the good fir

trading areas (Stark, 299). By the

early part of that century HBC had successfully driven out all competing

interests including Aster’s Northwest Company along with the North American

Fir Company. This was largely due to

continuing government support, a keen management spirit, a strong maritime

transportation structure, and an active and well connected fir trading market

throughout the world.

There

is no question that Great Britain

had a strong claim to Cascadia, (the Disputed Area as it was known), that is,

the land north of the Columbia River now western

Washington

State. Early explorations by Cooke,

Vancouver, Mackenzie, and settlers such as John McLaughlin (Bown, 60) had

solidly established these territories as British. After the treaties of 1817 Great Britain ALLOWED joint occupation of the

Oregon Territory for 10 years, (to be extended indefinitely in 1827), knowing

full well that the land north of the Columbia was theirs by right of discovery

and occupation. The British

immediately seized the opportunity by encouraging HBC to continue expanding an

already strong presence by constructing many Columbia River based forts (fir

trading centers) even in Puget sound itself; Ft. Colville (1825), Ft. Vancouver

(1825), Ft. Nisqually near Tacoma (1843) as well as Astoria which itself was

briefly held by Britain during the 1812 war. These forts were all north of the Columbia River

occupying Cascadia. The forts were, by the way, not really forts but factories

in the sense that fur was purchased, brought in, collected, sorted, tanned and

stored for shipment. The designation

Ft. may have been an abbreviation for factory and the factory boss or director

was called the factor. Meanwhile the

US

government did nothing to strengthen or support any kind of effort to colonize

or occupy the region.

Dr.

John McLaughlin, who was the factor of Ft.

Vancouver

from 1824 to 1845, encouraged newly arrived settlers to move south of the

Columbia

and establish settlements in and around Oregon City

on the Willamette River where he claimed the soil was much richer. It was. He had long convinced

himself that the Cascadia region would absolutely become British territory once

the American Government came to its senses, so he retained his Canadian

citizenship. By 1840 that area was under total control and administration of the

British.

John McLaughlin was a good man.

He

helped many of the early pioneers with loans, supplies and advice. He worked tirelessly for HBC but was ignominiously dismissed 1845 because

of non-performance. Actually it was

because the fir trade had collapsed. One

year later the treaty was signed giving Cascadia to America. He retired to his home in

Oregon City

and was resented by the locals who were quick to accuse him of injustices and

misappropriations. After his death

his memory was exonerated and he became sort of a folk hero.

John McLaughlin was a good man.

He

helped many of the early pioneers with loans, supplies and advice. He worked tirelessly for HBC but was ignominiously dismissed 1845 because

of non-performance. Actually it was

because the fir trade had collapsed. One

year later the treaty was signed giving Cascadia to America. He retired to his home in

Oregon City

and was resented by the locals who were quick to accuse him of injustices and

misappropriations. After his death

his memory was exonerated and he became sort of a folk hero.

But

1840 became a year of turmoil for the young United States. Our government was hopelessly and

completely torn over Texas

and slavery issues, we were still recovering from the disastrous 1812 war with Britain, and the stock market had crashed in 1837 creating a large population of

restless homeless farmers. Uncertainty

and revolt was upon the land.

I have indentified three major events which probably shaped the future of

northwest and western

Washington. These events very likely persuaded

the British that a prolonged struggle to retain its Cascadia lands was not only

futile but hopeless. It was no small

task to force Britain

to give up its solid hold on Cascadia,

especially in light of it’s long colonial tradition. The Americans were not getting away with it again, or were they?

The Nootka Affair

Sources:

Buck, Rinker, The

Oregon Trail, 2015

Toll,

Ian, Six Frigates, 2006.

Horwitz, Tony, Blue

Latitudes, 2003.

Borneman, Walter R., Polk, 2008.

Borneman, Walter R., Rival Rails, 2002.

Bown, Stephen R., Madness Betrayal and the

Lash, 2008.

McCrum, Robert, Cran, William; MacNeil, Robert., The Story of English,

1986

Stark, Peter, Astoria, 2015

* Borneman cited from Polk unless otherwise indicated

When

I was a little kid living in Everett, Washington I used to go down to the long narrow park on Grand Avenue

a few blocks from where I lived. A

big tree hung out over the steep bluff dangling a sturdy rope, and it was great

fun to grab the rope and swing out into the abyss way over the brambles and

blackberries far below. It was even rumored that a kid had been killed on those bluffs. Today the place is called

Grand Avenue Park.

When

I was a little kid living in Everett, Washington I used to go down to the long narrow park on Grand Avenue

a few blocks from where I lived. A

big tree hung out over the steep bluff dangling a sturdy rope, and it was great

fun to grab the rope and swing out into the abyss way over the brambles and

blackberries far below. It was even rumored that a kid had been killed on those bluffs. Today the place is called

Grand Avenue Park. Casual

research leads me to wonder why and how Seattle

and Puget Sound ever managed to wind up in the United States, a question that may surprise some but still a very worthwhile question to ask

especially since the British were not much inclined to give up hard fought for

and painfully acquired terratories.

Consider that all this area was explored by the British, settled by the British,

fortified by the British and occupied by the British before we came along. So what happened?

How did we get it?

Casual

research leads me to wonder why and how Seattle

and Puget Sound ever managed to wind up in the United States, a question that may surprise some but still a very worthwhile question to ask

especially since the British were not much inclined to give up hard fought for

and painfully acquired terratories.

Consider that all this area was explored by the British, settled by the British,

fortified by the British and occupied by the British before we came along. So what happened?

How did we get it? John McLaughlin was a good man.

He

helped many of the early pioneers with loans, supplies and advice. He worked tirelessly for HBC but was ignominiously dismissed 1845 because

of non-performance. Actually it was

because the fir trade had collapsed. One

year later the treaty was signed giving Cascadia to America. He retired to his home in

Oregon City

and was resented by the locals who were quick to accuse him of injustices and

misappropriations. After his death

his memory was exonerated and he became sort of a folk hero.

John McLaughlin was a good man.

He

helped many of the early pioneers with loans, supplies and advice. He worked tirelessly for HBC but was ignominiously dismissed 1845 because

of non-performance. Actually it was

because the fir trade had collapsed. One

year later the treaty was signed giving Cascadia to America. He retired to his home in

Oregon City

and was resented by the locals who were quick to accuse him of injustices and

misappropriations. After his death

his memory was exonerated and he became sort of a folk hero.