| You must be in a hurry for trouble. From here to Eternity |

Dominic Vautier

updated 6/2014

email

For well over 100 years the world has been making music by putting it on some kind of surface. In the beginning music cylinders were made but these were fragile, hard to copy and difficult to transport. The Victor Company pioneered flat records that were quite easy to copy and we continue to use just about the same thing today. Of course the media has gone into the future and now use digital that can be in many forms and can support a variety of players and can be stored on memory sticks and chips. We still like to make records probably because they are of really good quality and all analog, last a long time, and well, we have a lingering nostalgia for them.

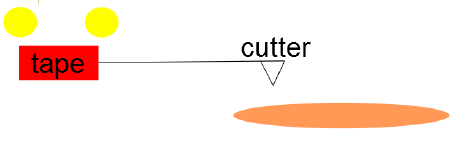

So early records evolved into flat disks because they were easy to make and the machines that played them were easy to make. The sound was first cut into soft wax or other material called a lacquer, that is, a flat round piece of material that rotated while a cutter blade impresses little wiggles that can produce sound on a player. Lacquers were made in three quite different ways depending on the period of technology. The front end of this manufacturing process changed dramatically; the back end did not.

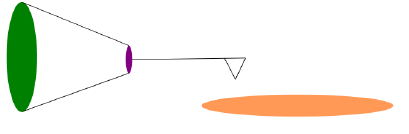

The

first and earliest way of capturing sound was by using a big horn fitted with a diaphragm

that moved a cutter blade based on air pressure from the singer or player.

This diaphragm generated wiggles while the lacquer disk was

spinning at a certain rate. The operation required a lot of sound waves along with strong lungs

and loud instruments, often distorting things badly. But it was an exciting beginning. Many of these

recording horns could be placed in one room to get additional copies.

The

first and earliest way of capturing sound was by using a big horn fitted with a diaphragm

that moved a cutter blade based on air pressure from the singer or player.

This diaphragm generated wiggles while the lacquer disk was

spinning at a certain rate. The operation required a lot of sound waves along with strong lungs

and loud instruments, often distorting things badly. But it was an exciting beginning. Many of these

recording horns could be placed in one room to get additional copies.

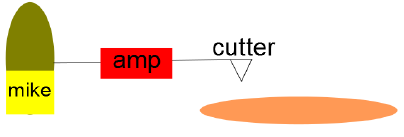

Next

came some electronic assistance where sound went into microphones and was

amplified causing the cutter to cut much more accurately.

People did not have to sing so loud and musical instruments sounded better.

Next

came some electronic assistance where sound went into microphones and was

amplified causing the cutter to cut much more accurately.

People did not have to sing so loud and musical instruments sounded better.

The final

big

development consisted of high quality tape recordings (thanks to the

Germans) which were able to generate an electronic signal that then could

drive a cutter

blade more accurately. This was huge because you

had musical backup and Bing Crosby finally got to take a break from singing.

The final

big

development consisted of high quality tape recordings (thanks to the

Germans) which were able to generate an electronic signal that then could

drive a cutter

blade more accurately. This was huge because you

had musical backup and Bing Crosby finally got to take a break from singing.

Of course lots of big improvements continued as time went on. The tape recordings were replaced by computer hard disks that produced the signal for a cutter.

This above discussion was only the first step in record production, getting a lacquer and a master that is.

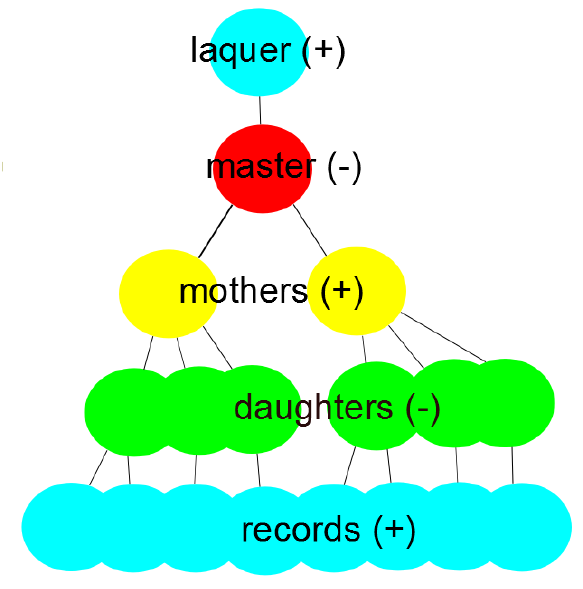

Below I signify a plus (+) to mean the record surface consists of

groves and can be played. I

use a minus(-) to mean that the record is negative and consists of hills

and is not playable.

When the lacquer was done being cut by whatever means it was sprayed with a silver-nickel solution which cools to form a master (-). The lacquer is then pealed off and discarded. In the early years the master was very very important because it was the truest representation of the music and was also as close to the original as possible. If this master got lost or damaged the music was literally gone forever.

The master stamps several mothers (+). How many mothers depend on how many records they expected to produce and how much they wanted to risk degrading the master through continued stamping. Each mother can then stamp out many daughters(-), again depending on sales volume. The daughters, or stampers can then stamp away until they ware out. They do ware out. The quality of any record depends on the condition of the daughter and how many times it was used.Much also depends on the air environment because any dust particle can be picked up in the record at any stage of the process. Companies that manufacture records are not making computer chips, but they do try to keep the air clean to a high level. But companies have different levels of quality, just like cars so don't buy Friday cars and records.