D Vautier

5/22

The three minute barrier states that the proper duration of a song is around three minutes. History suggests that as recording technology progressed, length restraints no longer existed but the three minute rule seemed to continue. Why so? Possible explanations for this is rooted in history itself, tradition, customs, and to a lesser extent, believe it or not, technology. Or then again, perhaps it was just as simple as a human time clock that refused to adjust? Was the three minute rule a strictly an American phenomenon or was it caused by other factors? Europe and the rest of the world had no specific time limits on their music. They had no built-in time clock. Why were we Americans automatically drawn into three minute music? Let us look a little deeper at the history of American music.

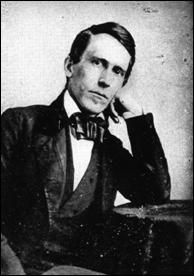

Stephen Foster was the first true American popular songwriter. He published his first song in 1844 and set a pattern for American music. Of course his work was hampered by modest market growth and slow, limited song exposure. The really big hits of this antebellum era were lucky to sell 50,000 copies of sheet music and enjoyed only limited geographical exposure. Being a song writer in those days also was far from a lucrative occupation. In fact it was considered more of a hobby and not a real job. There just wasn’t a very big market and it took many years for any song to achieve reasonable public recognition. The music tended to be limited in style, and often quite provincial so the appeal was far from universal. We, as a country were not yet formed.

Foster’s music falls into two general categories, the ballad which could vary in length from three minutes to perhaps five, and the dance song which by its nature seemed to be limited by comfortable human endurance, that is, around three minutes. Examples of the dance song are De Camptown Races, Ring De Banjo, Oh Susanna and many others. It seems clear that Foster had a strong influence over the industry from its very beginning by the fact that the songs of subsequent writers; Bland, Rosenfeld, Kennedy, McGlennon, and others are often indistinguishable from his own work but these subsequent songs had one thing in common; their average length was three minutes.

American Musical development languished after the death of Foster in 1864 then came back to life around 1885. Some historians have attempted to explain this “dry” musical period as the natural result of various forces: nebulous standards, public indifference, the sudden preeminence of other musical forms (mostly British), a weak market, a disorganized distribution system, nonexistent copyright laws, and an unusual dearth of musical talent. Much of the music of that period was passed on to us through forms such as minstrelsy and vaudeville, which I will discuss later.

But Americans in general rejected European influence, preferring their own home grown material, and to the eyes of the rest of the world America remained a backwater of cultural and musical inferiority.

In 1893 a lot of things changed very quickly in America when the smash hit After the Ball and Daisy Bell were both published. This particular year ushered in a different kind of music that Americans could actually claim was truly theirs. This early popular music period (1893-1915) saw the birth of music that looked and felt distinctly and definitely American. It was marked by a drastic change in form, tempo and content. Its appeal was sudden and widespread, while the demand for sheet music absolutely exploded. Slow, sexy waltzes and quick, snappy one-steps began to roll out of tin-pan alley directly into the many dance floors and ballrooms of New York and other large cities across the country. A new kind of songwriter began to dominate the music industry; young, aggressive writers who were bold and forthright in their musical statements. People like Harry van Tilzer, Gus Edwards, Joe Howard, Paul Dresser and others became rich and famous. Sexual themes were introduced into popular music in 1900, and by 1909 they had become generally accepted. But It all depended on sheet music because there were no records or phonographs or radios.

For most of this country’s history up until recorded music, sheet music has been the record keeper for American song. It was the only media available to the industry for a good part of the last two centuries. No other way to communicate song existed except by word of mouth (or ear). Serious recorded music only began after 1915.

Sheet music came in two sizes; the old style song sheet measured about 11 inches wide and 14 inches high, and the smaller size sheet was 9 by 12 inches. Pieces were printed in the large size until about 1910, when piano music holders began to get smaller and publishers wanted to save paper and transportation costs. The 9 by 12 size started appearing about that time and became the standard after World War One. Some music came in books of songs, marches, or waltzes, but most of the time each piece contained one song and was usually made up of one double folded sheet with a single sheet inside, making a total of three pages or six sides. Since the front side was for the cover and the back side for advertisement, just four sides were left for music. Worse still, sometimes the last two sides were sometimes used for advertisement, restricting space for printed song material even more. Songwriters had to deal with this restriction when they considered publication. Consequently, most songs had to be basically written and arranged in a way that accommodated four printed sides or perhaps less. This effectively reduced the song duration to around three minutes.

Early in the development of sound for entertainment, Alexander Bell, along with his cousin Chichester Bell and a brilliant young assistant Charles Tainter, formed a research team called the Volta Group. This team began to improve on sound recording and playing by cutting a groove into a surface rather than just denting tinfoil. The Volta group also patented the zigzag approach to sound reproduction, where the stylus moved back and forth following a groove on the recording surface, as opposed to Edison’s hill-and-dale technique where the stylus has to track up and down to generate sound. Another valuable contribution from the Volta Group was the flat record and the free-floating stylus and arm that was driven by the groove itself rather than a tracking screw mechanism. This free-floating feature brought about a vast improvement in sound quality and expanded play time. On this point it is to be noted that the three minute feature was an absolute necessity since that was the music length then in use. The Volta Group did not dictate song length but simply facilitated what was then in use. If they needed to design a four minute machine they would have done so.

The Volta Group eventually became the American Graphophone Company and began to market their first product, the famous, though not too successful, Graphophone. The optimum playing time of these crude playing records was about three minutes.As recorded music evolved and its quality was enhanced, it affected the way music was interpreted by the public. Instead of just small-town talent demonstrating a song on the piano at the local barber shop, a big-name artist could interpret the music. The general public would be awed, and only those with the greatest talents would feel adequate to perform the music once the recorded version became popular. Even then, they mimiced the original recording which tended to follow the three minute rule.

After 1900 three big record companies controlled 95 percent of the record industry, The National Phonograph Company, Columbia of Washington, and the Victor Company.

Berliner’s Victor Company began marketing its hugely successful gramophone, using the technology of zigzag tracking developed by Berliner himself. In 1896 Berliner hired Eldridge Johnson, a talented and enthusiastic engineer, to design and build a spring-driven motor for his gramophone which was designed to run a three minute record without rewinding or loosing pitch. Within a short time Johnson was able to redesign not just the spring mechanism but the entire gramophone. He made many other improvements.

What about classic ragtime? A typical piece runs way longer than three minutes. It is difficult to define Classic Ragtime or relate it to this discussion because it’s not really popular music at all, and it’s not Jazz or Blues but it does introduce syncopation (hence ragtime (raggedy-tempo)). It’s strictly piano music very much like classic sonata, somewhat like a fugue or baroque counterpoint, but with definite differences, one of which is playing time as I mentioned (more than three minutes). Classic Ragtime contains intimate rhythmic interactions you might say between the left hand treble and the right hand base. The right hand is usually heavily syncopated and melodic in contrast to a straight left hand set rhythm. Moreover, a Classic Ragtime piece usually contains three melodies, each with its own rhythm, interacting in different ways. Classic Ragtime can be loosely compared to a dialogue between the left and right hand on the piano. Sometimes they play together, sometimes they fight, but most of the time they just talk to each other in interesting ways.

It is only by listening to Classic Ragtime that one can appreciate its vibrant nature, flowing quality, and unimpeded buoyancy. Two excellent examples of this can be found in the music of Scot Joplin. They are the Swipsey Cakewalk (1900), and Easy Winners (1901), both of which are representative of his best work.

Casual historians incorrectly argue that Classic Ragtime had a significant effect on the course of early popular music and usually represent the period through this lens. This is not the case. There was only one Classic Ragtime hit, Maple Leaf Rag, that even made it to the million-seller mark, and it wasn’t really good ragtime. All the other successful ragtime music, such as Hello, My Baby, Bill Bailey, and Alexander’s Ragtime Band were popular ragtime, a very different kind of music altogether. Maple Leaf Rag was considered sort of a novelty song because nobody could figure out exactly what to do with it. They couldn’t deal with a song that wasn’t danceable and had no words. This was the case, essentially, with all Classic Ragtime. There were virtually no popular songs of this era that contained the signatures of true Classic Ragtime, that is, music without words and having difficult or undanceable syncopation. However it is of note that all three parts of any classic ragtime piece was around three minutes long.

The first British musical invasion of America started in 1878. The Operetta or Light Opera was strictly an English import, usually a comedy, featuring complex and often convoluted plots, intricate musical scores, and very lighthearted themes. The music was a blend of slow ballads and fast tongue twisters, which relied heavily on clever rhyme and verse, far too rich for the common American palate. In an indirect way however, the English operetta had some influence on American popular music development. Let me explain:

In 1878, H.M.S. Pinafore opened in Boston. Its immense popularity brought a whole new clientele to the theater, namely entire families, men, women and children. Before Pinafore, the stage was looked upon with suspicion by most respectable families. After Pinafore, the stage became a legitimate source of family entertainment, bringing in many new customers and producing more revenue, thereby attracting better-quality subject mater. The result of this evolution was the creation of a market, i.e., the development of enormous possibilities for making money, not just from operettas, but from any type of theater. This suddenly-expanded market caused vast amounts of new material to be fed into the entertainment machine, which also served as grist for the two popular music mills, Broadway and Tin Pan Alley.

The term Broadway, for our purpose, refers to American Musical Comedy, a distinctive and completely American form of musical theater that was able to integrate music and story into a smooth presentation. The first American musical production that in any way resembled this was The Black Crook, first performed in 1866. It was a far cry from the musical theater that developed 35 years later around the turn of the last century, but it was a beginning.

The modern Musical Comedy is a type of stage performance placed in an American setting, usually dealing with American social problems, and having a tightly woven relationship between music and story. The first true musical comedy was said to be George M. Cohan’s Little Johnny Jones, although others claim that Babes in Toyland was the first. In any case, by the first few years of the last century the American Musical Comedy had established itself as a viable and popular form of American theater. It was to reach its perfection in 1947 with South Pacific, and has now evolved into what some refer to as a musical play. The songs of Broadway musicals were specifically designed to be transferable into popular music and thus had to comport to the three minute rule.

Popular music has always tried to use Broadway as a source of material, and in the earlier years there was a significant amount of Broadway music that became popular. This still happens today, but during the years when popular music was just getting established (1892 through 1915 in particular), borrowing from Broadway was quite common. Of course, many of the writers of that time moved freely between Broadway and the popular music industry so it was natural that these industries shared much of their material. The very physical closeness of the two forms of music also tended to encourage a lot of sharing. Music written for Broadway that turned out to be unusually successful was automatically published as popular music pieces and was therefore designed to fit into that genre. Popular music, while generating its own material, borrowed heavily from anywhere it could anyway, and Broadway was, at that time, a very convenient and lucrative source.

Vaudeville is a fast moving variety show featuring, different acts, songs, dances, burlesques, and skits. Through this type of entertainment, the customer is exposed to a non-stop array of entertainment forms, like going to movies in the old days when audiences were not concerned with start times or ending times, and came and went at their own convenience.

There were jugglers, acrobats, animal acts, skits, burlesque, singers, strong men, magicians, slapstick, and even audience participation, usually in the form of “plants” who did everything from singing to throwing tomatoes. The format, unlike the more structured minstrel show, was loose and unrestrained. Many actors and songwriters preferred vaudeville because of the open and generally unrestricted format.

This open-ended continuous stage presentation was a career springboard for actors and singers who needed an opportunity to refine their skills before entering areas of more serious and lucrative entertainment. This included many notable people such as Irving Berlin, Jack Benny, George Burns, Eddie Canter, W.C. Fields, and Al Jolson. But as Vaudeville gradually moved to Hollywood after 1915, and so did the talent.The first Vaudeville may have appeared in the 1880’s around New York. Some suggest that it started because saloon and dance-hall owners began losing business to other forms of entertainment. However, vaudeville probably began sooner than that, perhaps as early as 1865, and for a variety of other reasons. Saloon owners did however organize a type of loose-formatted casual theater. They obviously relied on less artistic forms of entertainment that were more appealing to their clientele and indulged heavily in satire, sleaze, and social comment.

In a word vaudeville was a bottom-dweller, a garbage collector, the vacuum cleaner of early entertainment. It sucked up everything left over by more respectable forms of music. It was truly low comedy at its highest.

Even though vaudeville was long considered “lowbrow” entertainment because of its crude humor and raucous performances, by 1910 it had been forced to acquire a degree of respectability. By that time, the market was drying up and vaudeville needed to forsake its erstwhile ways and offer more family-oriented entertainment to increase audience attendance.Vaudeville did play a very important part in the development of mainstream music and contributed to shorter song times. Any act or number that lasted more than expected got the “hook”. It was in a unique position to attract, collect, and use song material that catered to the lowest common denominator, and for this reason it often had very wide public appeal. It gave its customers what no other type of entertainment at that time was able to give. Often this entertainment took on the form of cheap girlie acts and sexy songs that could not be performed in more respectable venues like Broadway and off-Broadway.

During these early years from 1893 until 1915 and well beyond that, there was no single larger source for mainstream popular music than vaudeville. Many writers preferred to try their music out on the vaudeville stage because audiences gave them the direct feedback they needed. Moreover the format was somewhat free of censorship and writers could be much more creative and test the limits of respectability. All this variety generated an uninterrupted source of rich material for the popular-music machine. The relationship between early popular music and vaudeville remained very strong, and the point where one left off and the other started is hard to distinguish.

The first stage

presentations of minstrel shows occurred as early as 1844, around the

same time that Foster started publishing. Minstrelsy was a type of musical theater that tended to follow

a prescribed format and use a predefined set of characters. It became very popular just before the Civil War.

The great pioneer in this field was Edwin Christy, who

developed what many considered the standard format. An interesting thing about minstrelsy is that it utilized some

of the basic ideas of Greek Drama. The blackface and whiteface were masks or “persona” which

transformed an individual into something else, a stage actor. Also, as in Greek drama, women were not allowed to act and the

parts of females were traditionally played by men or boys. As the 1800 hundreds wore on, the exclusion of women began to

disappear and it became more common for women to appear in minstrel

shows.

The interlocutor, or middleman, is usually in whiteface, well dressed, acts as master of ceremonies, and controls the general pace of the show. His demeanor is proud, haughty, and condescending, representing the upper class, businessmen, land owners, and politicians. At the end of both sides of the semicircle of performers are his arch antagonists, Mr. Bones to his left and Mr. Tambo on his right, so named because they play bones (castanets) and tambourine, respectively. These two people, known as end-men, are always in blackface and are dressed in colorful and often outlandish outfits. They continue through the course of the program to ridicule, belittle, and torment the unfortunate interlocutor, making all manner of jokes at his expense. The interlocutor is slow of mind and manner, and purposely acts as the butt of all these jokes. By the way, the jokes are very bad. Take this example:

Bones:

Mr. Interlocutor, I’d like to ask you a question.

Inter: Why certainly. Go ahead Mr. Bones.

Bones: What has four legs and flies?

Inter: You’re not going to pull that old one on me again, are you?

Bones: Why you just don’t know the answer do you?

(laughter)

Inter: Of course I do. It’s a dead horse.

Bones: Wrong, all wrong.

(mild laughter)

Inter: I’m wrong? Well

suppose you tell me then what has four legs and flies.

Bones: Two pair of pants.

(great laughter)

The second part of a typical minstrel show, called the Oleo or variety show, consists of specialty acts and non-stop comedian performances, soft-shoe, tap dances, and the like. The third part is called the burlesque or conclusion, which is a review or parody of the first two parts. It may be composed of a skit, a farce or a short one-act play.

Throughout all this evolution and experimentation, however, the characters of minstrelsy remained much the same: the middleman (in whiteface, proud, haughty, well dressed, slow of mind) and the end-men (black-faced wise-guys, smart-alecks, outlandishly dressed). The end-men symbolized the common man, that is to say, the audience, and when the smart-alecks directed their ridicule at class structure, they spoke for the masses. Common folk felt that social position, power, and wealth did not reflect essential human worth, and that all people were equal, in life, in death, and on stage. Minstrelsy sang the praises of a society without class. It was indeed a classless act.The reader needs to remember that the blackface motif associated with Minstrelsy was not intended to constitute a racial put-down in the way we may understand it today. Rather, blackface was chosen at that time because it was a powerful way to deliver satire, something that audiences could readily understand, and it was practical as well. First of all, the easiest way to become a different person while on stage was to assume some kind of disguise, and burnt cork was a cheap and available commodity. Secondly, the black tradition offered a stereotype of the quintessential “common man,” who did not equate wealth or social position with essential human value. This stereotypical man in blackface offered the audience a character to identify with. He was fun-loving, uninhibited, lazy, and disposed to laugh at the expense of those who were pompous, haughty, and self-impressed, and the average folks in the audience were more than glad to laugh along with him.

The inclusion of the stereotypical black man may most likely be considered racist in today’s world, but a few additional things must be kept in mind. First, the character in blackface was a “wise-guy,” and he was never the butt of the audience’s laughter. He was, instead, the audience’s accomplice in the assault on class distinctions. Second, in 1844 any and all ethnic stereotypes were considered fair game. In an era when racial sensitivity and political correctness were virtually unknown, people accepted the use of ethnic humor as just one more thing to laugh at. Third, there was a necessity, just as in Greek drama, for the actors to assume a stage "persona," that is, the character of an unrecognizable person while on stage. That on-stage actor had to be essentially disembodied, completely disassociated from the actual person who played the part, and this was accomplished by wearing a "mask." That "mask" was burnt cork. The effect is similar to the strict rule at Disneyland that a cartoon character must never, ever, be seen partially out of disguise because it destroys the illusion.Minstrelsy was important in the development of popular music for it became the custodian for much of Foster’s music, and his tradition played a key roll in the subsequent development of popular music. After all, it was Edwin Christy, organizer of “Christy’s Minstrels,” who purchased and performed many of Foster’s songs. This inclusion of Foster’s music in minstrel performances preserved and protected his song tradition through the so-called “dry” years (between his death in 1864, and the beginning of the popular-music era in 1892). Without this preservation, the strong influence of Foster’s work on popular music may have been lost.

Keep in mind also that for, a long time, popular music cast envious eyes on the minstrel way of singing and even went so far as to develop its own brand of blackface. Blackface then became a legitimate subset within popular music to support and identify with heavy syncopation and snappy tempos, techniques that were not quite yet accepted in the mainstream. Irving Berlin, the Von Tilzer brothers, Al Piantadosi, Fred Fisher, and other top-rate writers of the period intentionally wrote popular songs in blackface in order to use these catchy rhythms and syncopations. It worked great. Those who deny the significance of minstrelsy in American music and who base this denial on some kind of racial or ethnic prejudice do a disservice to its considerable contributions.

Playbills from minstrelsy programs seem to support longer intervals between numbers and this may be due to an allowance for pauses, laughter, add-lib, improvisation and other interruptions but song content was definitely borrowed from the programs and the song content seemed to last about three minutes.No other dance was ever as popular during this early American musical period than the slow American Waltz. Of the many songs which were popular during this period in America and which sold over a million copies, most were waltzes. Not only did waltzes predominate by sheer numbers, they became the absolute blockbusters. The really big early sellers such as After the Ball, Daisy Bell, Bird in a Guilded Cage and the beer hall songs of Harry Von Tilzer blew away the competition. As late as 1909 the waltz was still without any question the biggest seller and the dominant dance of the ballrooms. The double whammy hits of that time, Meet me Tonight in Dreamland and the following year, Let Me Call You Sweetheart again blew the charts to pieces. Together these two slow waltzes sold over 10 million copies in a short period. America was truly waltz-crazy.

Writers

mistakenly characterize this period as the “Age of Ragtime” or the

“Ragtime Era” or something more commonly understood, because

the waltz is not very exciting to those who never experienced it.

However, the facts speak otherwise. If anything, the era should most appropriately be called the

“Slow American Waltz” period because this was by far the dominant

dance of the day. It is

most important to note that Americans did not necessarily use the

standard waltz box step but rather converted it into sort of a two-step.

Waltzes gradually gave way to the one-step. The one-step was a collection of dances loosely termed “Ragtime Dances” or more correctly, popular ragtime dances, which emerged to handle the massive increase in young people looking for an easy dance that could be done to the faster music tempos and syncopation that was quickly coming into vogue. The one-step was a general term for any kind of dance that used a constant tempo with one step taken to each beat of the music. This dance easily handled the new forms of syncopation and allowed the dancers more freedom of expression. The one-step was eventually able to assume a lot of variations such as the Turkey Trot, the Grizzly Bear, the Bunny Hug, The Boston Dip, The Shiver Dance, and The Hug-Me Close. The evolution of the one-step into a number of variations is quite similar to what happened in the 1960’s with The Twist, The Monkey, The Swim, The Locomotion, Mashed Potatoes, The Watusi, The Limbo and other off-shoots of basic rock dancing.

A further advantage of the new dance was that it could be done at different tempos. Speeding the music up or slowing it down didn’t make it any more difficult to dance. The only restriction was physical exhaustion but usually the three minute rule prevailed.

One popular variation of the one-step was the Cakewalk, which differed from other one-steps because it was always open-coupled. This means that the couple danced side-by-side instead of facing each other, and the line of dance was directly forward instead of at an angle, like the normal one-step. The early cakewalk is hard to recommend to anyone who is not an athlete. It requires a very flexible spine and a good sense of balance. It is a little reminiscent of the Limbo Rock dances of the 1950’s, where the person who dances lowest under a pole wins. Just as in the Limbo Rock, the Cakewalk requires the dancer to lean backwards. The difference is that you have to strut like royalty at the same time that you are leaning back at an angle, and usually wind up flat on your butt or in bed the next day or both.

The one-step cakewalk could be danced to any of the syncopated full-time pieces of the late 1890’s. Popular cakewalk pieces were Bill Bailey, Hello, My Baby, My Gal is a High Born Lady, and I’d Leave My Happy Home For You. The cakewalk got its name, by the way, because the couple who did the best cakewalk, won the cake. It was limited to around three minutes.

Cakewalks contributed some interesting terms to American metaphor. Doing anything difficult or outrageous certainly “takes the cake” because only by such exotic behavior could one hope to win a cakewalk contest. But by 1915 the cakewalk had become no more than a graceful promenade and the term instead began to mean something very easy to do; people therefore said, “it’s a cakewalk”, or “It’s no cakewalk.”

As early as 1910 groups of musicians began to appear and perform together at nightclubs and ballrooms. These consisted of a dozen or more who played trumpets, saxophones, trombones and drums. They performed instrumental numbers and jazz mostly. It was all dance music and each number lasted about three minutes on average. The bands often featured a boy or girl singer who would sometimes begin singing well into the number. The groups became quite famous during the 1930s and particularly during the war years, but then disappeared after 1946, mostly for economic reasons. But these bands left a trail of many good solid hits. Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Tommy Dorsey, Shep Fields and Glenn Miller were among the top bands. The boy and girl singers included Helen O’connell, Jo Stafford, Doris Day, Helen Forrest, Mildred Bailey, Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Dick Jacobs to name a few. Many of these singers went on to their own careers in the 50’s and 60’s.

The war years were especially unique for big bands in reinforcing the three minute rule. Many big bands toured throughout Europe and the South Pacific theater. Large areas crowded with GI’s usually had a shortage of women requiring that dance numbers be kept short so that all the soldiers were able to dance with the limited amount of available partners.

The period following the war years was studded with individual singers and smaller groups. Most of the songs of the 50s were dance numbers and dance numbers had to follow the rule. Rock and roll was no exception.By the early 70’s some noticeable exceptions to the three minute rule began to appear in popular music but these were ballads and not especially designed or intended to be danceable. American Pie arrived in 1971 in both a short form for dancing and also in a ballad form that lasted well over 8 minutes. In 1975 Queen released Bohemian Rhapsody which lasted about 6 minutes. Neither of these longer versions were considered dance numbers.

American dance music went through a number of very fast transitions in the decades after 1970 from fast rock to disco to Reggae to rap. But all of these mutations shared the three minute rule which, while strongly rooted in tradition, still had to consider the limits of human comfort and endurance. It could be a quick rock step or a flowing slow love dance or a jitterbug or any of a hundred dances, but popular music is fundamentally dance music and only occasionally listen-to or drive-to-work music. So the three minute rule became the guiding light of every composition, every melody, every catchy tune, every inspiration, every possible success story. If you wanted to have dance music you had to follow the rule.

There

is something irresistibly natural, expected, and pleasant about a song

that lasts for three minutes. It might be

simply the way humans are built or conditioned as a society. I noticed this

clearly when I

first listened to American Pie. My

question was “This is absolutely a beautiful

song but what is wrong with it?” It was just too long, that's what was wrong with it.

It

was more than what was expected from a dance song or just a plain old

listened-to song. It was uncomfortable.

It was unnatural. In

all the history of American dance music from Foster, record players,

Vaudeville, Minstrelsy, Big Bands, Broadway, sheet music, the length

was supposed to be and expected to be three minutes or so. American Pie

simply broke the rule.

There

is something irresistibly natural, expected, and pleasant about a song

that lasts for three minutes. It might be

simply the way humans are built or conditioned as a society. I noticed this

clearly when I

first listened to American Pie. My

question was “This is absolutely a beautiful

song but what is wrong with it?” It was just too long, that's what was wrong with it.

It

was more than what was expected from a dance song or just a plain old

listened-to song. It was uncomfortable.

It was unnatural. In

all the history of American dance music from Foster, record players,

Vaudeville, Minstrelsy, Big Bands, Broadway, sheet music, the length

was supposed to be and expected to be three minutes or so. American Pie

simply broke the rule.