John Harrison

|

At birth God gives you just

so much driving time - then you die.

D Vautier |

D Vautier

6/2019

John Harrison was born into a carpenter family but

decided to develop clocks and he was really good at it. He lived a quiet life getting married in 1718 (Sobel, 67),

remarried in 1726 and had two children and could have lived out a quiet successful

existence making great clocks.

John Harrison was born into a carpenter family but

decided to develop clocks and he was really good at it. He lived a quiet life getting married in 1718 (Sobel, 67),

remarried in 1726 and had two children and could have lived out a quiet successful

existence making great clocks.

But fate had other

plans. This quite remarkable man propelled the world into the new

area of discovery in precision clock design starting in the early 1700s.

He had an uncanny ability to solve clock problems, problems which

had dogged inventors for at least 300 years.

To begin with, Harrison noticed that pendulum

clocks were very sensitive to temperature changes because the length of

the arm changed with temperature so he invented the gridiron. It

consisted of alternate lengths of brass and steel with different

expansion rates. Using this

approach he was able

to develop a pendulum clock accurate to within seconds per month (Cronin,

30). He was also able to

invent a better escapement for pendulum clocks.

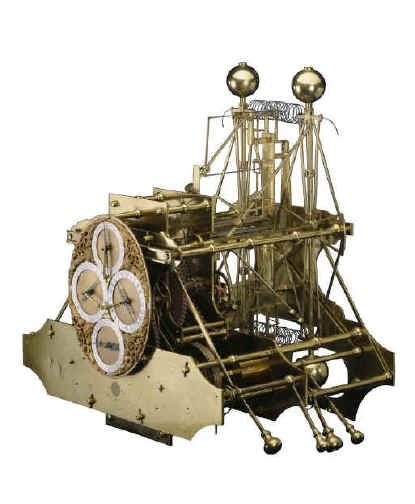

But it gets better. The world needed seaworthy clocks able to withstand temperature,

pressure, water and a great deal of shaking and radical movement that

came along with sea storms. Harrison

put his mind to developing chronometers or sea clocks (also called

regulators). For the next 20 years he developed three sea clocks the H1, the

H2 and H3. These were

monster clocks some weighing 75 pounds but H1 was probably capable of

performing well at sea and probably even able to win the £20,000

offered by the British Board of Longitude.

But Harrison decided not to compete because he felt he could do better.

By 1750 Harrison

fortunately gave up his crazy fixation on big sea clocks and realized that he could

get the same accuracy by designing and improving upon a smaller clocks.

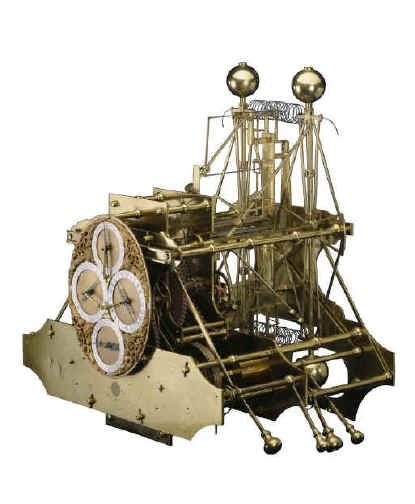

The culmination of his efforts resulted in the H4 which he completed in 1759.

It looked like a big pocket

watch five inches wide, and it

did in fact achieve incredible accuracy because his invention consisted of a

number of brilliant improvements in design. Harrison

was at first denied his £20,000 prize but eventually received it. He

died soon after in 1776 but he left a huge legacy. Not only had he

drawn much attention to world discovery and exploration by solving the

longitude problem, but he inspired many other inventers to improve on

the watch-making ideas he had introduced.

The H4 was far too valuable to be entrusted to any

additional ocean explorations so the board of longitude commissioned Larcum

Kendall to make several copies the K1, K2

and K3. These three

chronometers were involved in some fascinating adventures. The K1 went with captain James Cook on his second voyage who

became totally convinced of its capability. Cook again took K1 with

him on his last voyage. The

instrument survived but Cook did not. K1 was eventually recovered.

K2

went with captain Bligh aboard the Bounty

and wound up on Pitcairn island. This

is how Fletcher Christian determined that the island was unchartered.

Eventually K2 also was recovered and made itís way back to England.

K3 went off with Vancouver

to explore the northwest part of North America. Vancouver

did not particularly like the K3 and used it reluctantly to

verify the lunar distance method that he preferred (Bown,129) although he may have

claimed otherwise. Even though his

descriptions and methods were confusing, still his

longitudes turned out to be remarkably accurate, perhaps because of K3. But

then Vancouver was determined to use all existing methods available at

that early time in navigation (1792) including Jupiter's

moons.

The H1 in all it's ugly glory

The famous and beautiful H4.

|

John Harrison was born into a carpenter family but

decided to develop clocks and he was really good at it. He lived a quiet life getting married in 1718 (Sobel, 67),

remarried in 1726 and had two children and could have lived out a quiet successful

existence making great clocks.

John Harrison was born into a carpenter family but

decided to develop clocks and he was really good at it. He lived a quiet life getting married in 1718 (Sobel, 67),

remarried in 1726 and had two children and could have lived out a quiet successful

existence making great clocks.